Lions history: Briggs Stadium, the 49ers, Browns and the '57 championship game

The following chapter, titled "The Last Hurrah," is excerpted from “Miracle in the Motor City,” by Bill Morris. A history of the Detroit Lions since their last championship in 1957, the deeply researched book focuses on the Ford family’s six-decade stewardship of the team, culminating with this season’s playoff run. It will be published later this year by Pegasus Books in New York.

Morris grew up in Detroit and Birmingham, and he’s the author of five works of fiction and nonfiction, including the novels “Motor City Burning” and “Motor City.” He lives in New York City.

Briggs Stadium, the big sooty barn at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull just west of downtown Detroit, was buzzing by noon that Sunday, Dec. 29, 1957, even though kickoff was still an hour away. The teams had come out of their locker rooms to warm up — the hometown Lions in their blue jerseys and unadorned silver helmets and pants, the visiting Cleveland Browns all in white except for the orange globes of their helmets, an incongruous suggestion of sunshine and citrus on a team from the gray factory town where the combustible Cuyahoga River discharged its toxins into Lake Erie.

The winner of today’s game would be champions of the National Football League. The two teams were old familiars. The Lions had beaten the Browns to win championships in 1952 and ’53 before losing to them, badly, in ’54. As the players did calisthenics and ran pass routes and booted balls high into the sky, puffs of steam shot from their mouths. The temperature hovered above freezing — nearly balmy by end-of-year Midwestern standards, when football games were often played on fields that had turned to viscous soup or had frozen solid as a sidewalk. Today there would be no rain or sleet or snow. The field was dry, the winter grass patchy in spots, and the sun kept peeking through a tattered cover of clouds. Even so, this was one of the shortest days of the year, and the banks of lights on the stadium’s roof had already been turned on.

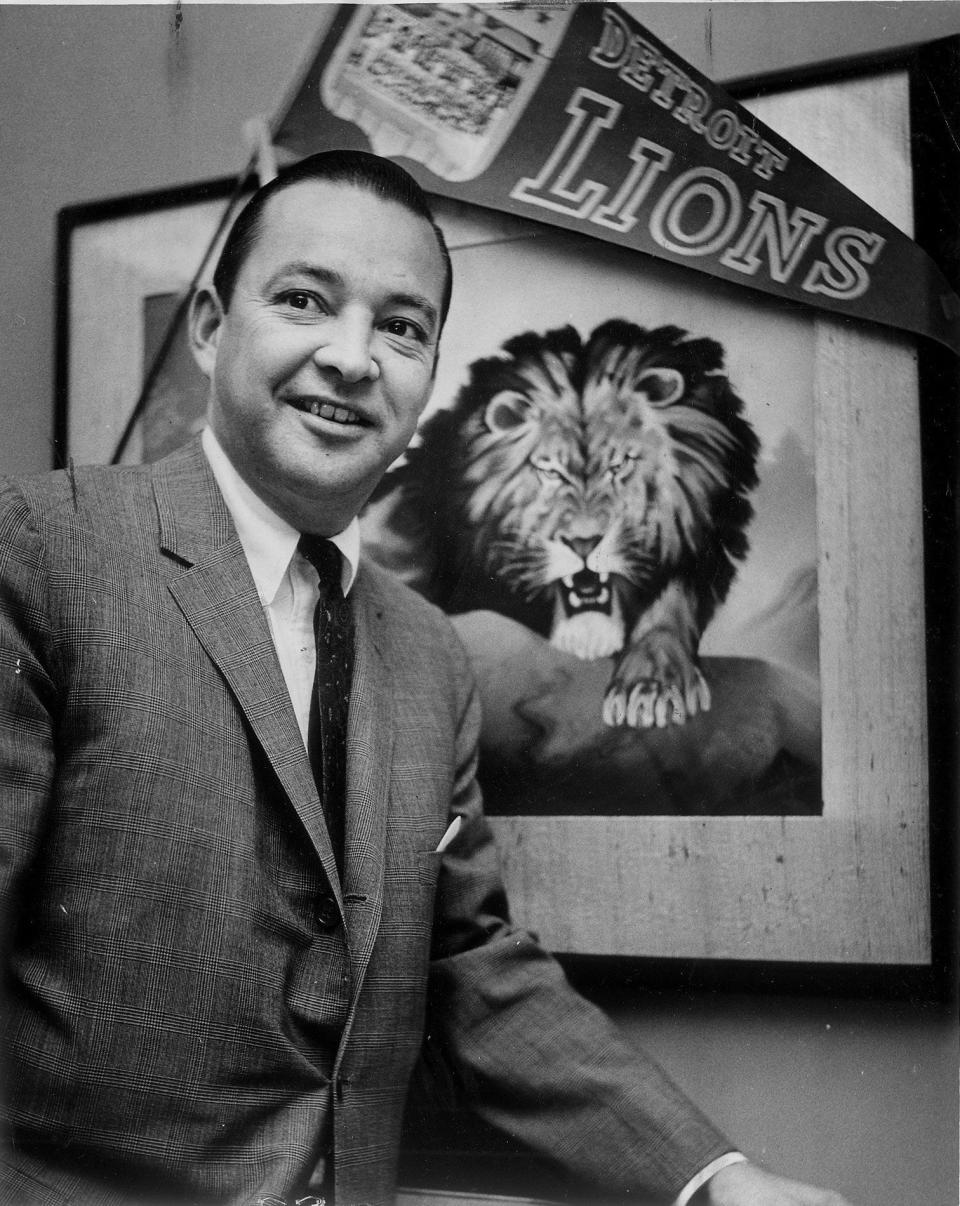

Among the 55,263 fans squeezed into the stadium that day was a dapper man who prowled the press box like a caged puma. This was a roofed aerie atop the second deck that curled around the corner of the stadium where home plate stood in the summertime, a reminder that Briggs Stadium was built for baseball, not football — for Tigers, not Lions. From up here you looked almost straight down at the field, a dizzying bird’s-eye view. The man pacing the press box stood apart from the blue-collar fans packing the seats beneath him. Instead of a nylon parka he wore a sleek camel hair overcoat and a cashmere scarf. His gloves were leather. A fedora rested atop his perfectly watered dark hair. He had been a Lions’ fan since he was a boy, and a year earlier he had bought into the 144-member syndicate that owned the team. Today, for the first time, he would find out how it felt to have skin in the game when a championship was on the line.

This was thirty-two-year-old William Clay Ford, the youngest grandson of auto pioneer Henry Ford, a man who’d been minted a multimillionaire the day he was born and had become richer, almost effortlessly, every day of his life. Now Bill Ford’s personal wealth was beyond imagining, a hundred million dollars — a billion in today’s money — maybe more, maybe much more.

Ford stopped pacing the press box and picked up a pair of binoculars so he could get a closer look at the activity on the field. His gaze landed on a man with a shock of yellow hair who was dressed in street clothes and sitting on a bench beside a pair of crutches. The man’s right ankle was encased in a plaster cast. This was Bobby Layne, the Lions’ star quarterback, a hell-raising Texan whose ankle was shattered during a late-season win over these same Cleveland Browns. Losing Layne was typical of the adversity that had dogged this team since training camp. Buddy Parker, the coach who’d led the team to those back-to-back championships in 1952 and ’53, had walked off the job in disgust before the ’57 season began. “This,” he declared, “is the worst team in training camp I have ever seen — no life, no go. It’s a completely dead team.”

One of Parker’s assistants, mild-mannered George Wilson, had stepped into the coaching vacancy. Then, during training camp, Layne got charged with drunken driving. He got off because the arresting officer, suddenly finding himself in an uncomfortably hot spotlight, decided that, yes, he might have confused Layne’s Texas drawl with the slurred speech of a man who’d had a few too many, a suggestion put forward by Layne’s inventive defense lawyer. After the charges were dropped, the team’s trainer posted a sign in the locker room: “Ah ain’t drunk. Ah’m from Texas.” Everyone thought that was very funny.

Including Bill Ford. He found himself drawn to these rowdy, rough, nearly unmanageable football players, especially Layne. Their go-to-hell attitude was so refreshing compared to the bean counters and brown-nosers you ran into in the sleek new headquarters of Ford Motor Company, known as the Glass House.

Now Ford’s binoculars came to rest on Tobin Rote, Bobby Layne’s backup, who was firing warm-up passes, grinning, chattering with coaches. Rote, another Texan, was a guy with a rifle arm who loved to run over defenders, and he looked relaxed out there, confident, almost cocky. Rote’s aura chased away some of Ford’s anxiety over Layne’s injury. The Lions had acquired Rote from the Green Bay Packers before the season in case something happened to Layne, and Rote had proved to be an invaluable insurance policy. After Layne’s injury, Rote had come off the bench and cemented the victory over the Browns, then he brought the team back from a 10-point halftime deficit to beat the Chicago Bears in the regular season finale. In those pre-American Football League, pre-Super Bowl years, the two NFL conference champions squared off in the title game without any playoffs. But the Lions’ strong finish left them tied with the 49ers for the best record in the Western Conference that year, which set up a playoff game in San Francisco. Down 24-7 at halftime, the Lions could hear the 49ers celebrating prematurely through the thin locker room walls. Enraged, the Lions roared from behind to win again, and so here they were in the league championship game, riding a four-game winning streak but battered, tired and stretched thin, clear underdogs to the well-rested and dangerous Browns.

Watching Tobin Rote throw his warm-up tosses gave Bill Ford a warm feeling. It got warmer when he got a smile from his wife Martha — Martha Firestone, the rubber heiress from Akron — who was sitting there in her mink coat with the other Grosse Pointe wives, sipping a cup of hot chocolate, trying to get her daughters, 9-year-old Muffy and 6-year-old Sheila, to quit darting around like a couple of minnows. Infant son Billy was at home, but soon enough he would join these Sunday family rituals.

It was time, at last, for the kickoff. The Lions’ kicker blasted the ball through the Cleveland end zone for a touchback, an omen of things to come. From there the game unfolded like a waking dream. The Lions scored the first three times they touched the ball, and by the end of the first quarter they had a 17-0 lead. It didn’t seem quite real to Bill Ford and a lot of other people in the stadium that day. After Cleveland’s Jim Brown, the Rookie of the Year, ran for a touchdown to keep the game within reach, the Lions faked a field goal and Rote lofted a touchdown pass to a wide-open receiver. The Browns were stunned. Then came the back breaker.

Just before halftime, Detroit’s defensive back Terry Barr snatched an interception at the Cleveland 29 yard line and scampered untouched into the end zone for a touchdown — a dagger that made the score 31-7. After he crossed the goal line, Barr simply flipped the ball to the referee and jogged back to the bench, tapping hands with teammates coming onto the field for the extra-point kick. Barr didn’t slam the ball into the turf, or do a dance, or run toward the nearest camera, or leap into the air while bumping his teammates’ helmets and chests. Why would he? He had simply done what he was expected to do, what he was paid to do. The message behind the subdued behavior of Barr and his teammates is clear: in 1957, sports had not yet devolved into just another branch of American showbiz.

Late in the fourth quarter, with dusk descending and the outcome decided, Bill Ford scanned the crowd. He was hoarse from yelling. As the clock ticked down, he saw that everyone was standing, bouncing up and down. Every I-beam in the green barn seemed to be shaking. A couple of jokers in the faraway centerfield bleachers had stripped off their shirts and were dancing in the aisles, no doubt fueled by repeat doses of Stroh’s beer and some antifreeze with a stronger kick. Bill Ford realized he was witnessing delirium.

The final score was an astonishment: Lions 59, Browns 14. Tobin Rote had passed for four touchdowns and run for another. Though no one knew it at the time, Rote’s performance would stand as the pinnacle of his seventeen-year career, much as this day would stand as the last hurrah for the Detroit Lions, who were about to embark on six and half decades of unrelenting futility. But that was the future. Now fans were streaming onto the field as the players carried Joe Schmidt, Detroit’s star linebacker and co-captain, around on their shoulders. Fans joined in the scrum. A city’s delirium was turning into pandemonium.

It had seeped into the locker room by the time Bill Ford pushed his way through the cigar smoke and champagne spray and bear hugs. He’d heard that Joe Schmidt and his roommate, the defensive lineman Gene Cronin, had planned to throw a post-game party, win or lose. After congratulating Cronin, Ford said, “I hear you and Joe are having a party.”

“Yeah,” Cronin said uneasily, not sure where this was going.

Ford surprised him. “Can Martha and I come?”

Cronin was in just his second season in Detroit, but that was long enough to figure out that you didn’t say no to a member of the syndicate that owned the team, especially if his name was Ford. Cronin gave him directions.

Driving to the party in his Continental Mark II with the heater roaring to chase away Martha’s chill, Bill Ford realized that what he loved about this day — what he loved about this game and this team and its fans — was that it all happened inside the chalked lines of the playing field, an orderly, violent, thrilling world that existed outside the suffocating world he had grown up in and was expected to remain in forever, playing by its rigid rules, locked inside the walls of the Ford family fortune and the Ford Motor Company. But what Bill Ford had witnessed inside Briggs Stadium today might be a chance to step away from the family and the company, a chance to be emperor of his own world. As he pulled up in front of Schmidt’s and Cronin’s apartment, the idea might have come to Bill Ford almost as an epiphany, unassailable, the perfect way out of his cage: I should buy the Detroit Lions.

The party was already at full roar, and Bill Ford dove right in. “So he and Martha showed up,” Cronin said later, “and at the end of the night they had to carry him out.”

It wasn’t the last time Bill Ford would celebrate a little too much after a Detroit Lions’ game. But it was the last time in his long life that he would celebrate them winning a championship.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Lions history: Briggs Stadium, the 49ers, Browns and the championship