Jordan vs. Dominique: When Indianapolis hosted the best Slam Dunk Contest of all-time

INDIANAPOLIS -- The 1985 NBA Slam Dunk Contest brought the old masters, the new masters and the man who would later be known as one of the ultimate masters of the slam dunk as an art form together in Indianapolis.

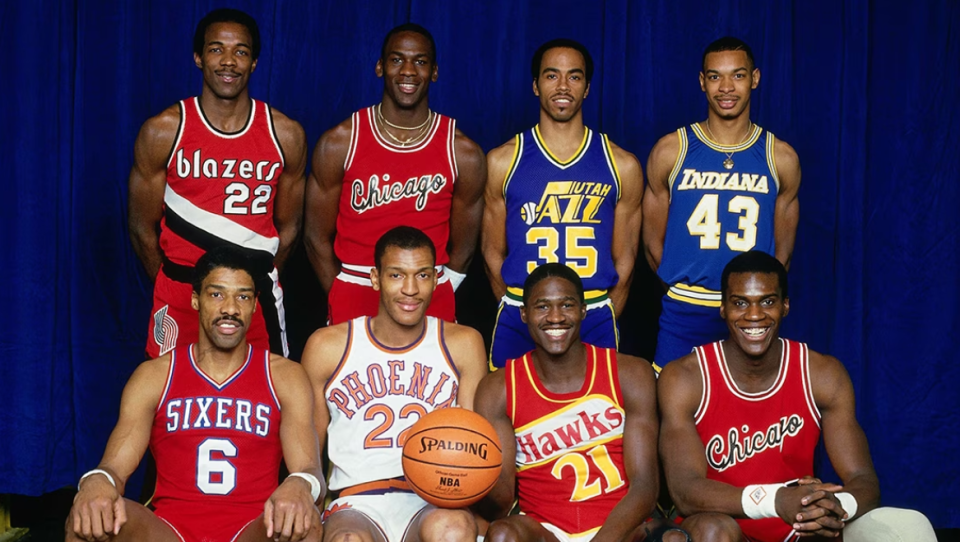

It served as a last hurrah for Julius Erving, one of the greatest practitioners of all-time, and the first edition of perhaps the greatest rivalry the event has ever known -- Dominique Wilkins vs. Michael Jordan. The field as a whole was legendary, quite possibly the best top-to-bottom collection of both dunking and overall basketball talent in the history of the event. Of the eight players who were part of the field, four became Hall-of-Famers, five were All-Stars at least once and one of the other three was the 1980-81 Rookie of the Year.

And a little-known member of the hometown Indiana Pacers almost stole the show entirely.

When the NBA All-Star Game last came to Indianapolis, the Slam Dunk Contest was in just its second year as a permanent fixture to All-Star weekend and it hadn't fully taken the shape of what it would become. It, apparently, wasn't broadcast live -- The Turner Broadcasting broadcast available that you can find on YouTube is very clearly edited for time -- and several computer glitches with scoring led to on-the-fly changes in the format including one that completely altered the event.

Judging purely on the star power and on the dunks themselves, the 1985 Slam Dunk Contest at Market Square Arena stands out as one of the best ever, and one that shaped what would follow. It was the first duel between Wilkins and the then-rookie Jordan, which Wilkins would win, and it also introduced the world to the creativity and leaping ability of one Terence Stansbury who could have and perhaps should have spoiled that duel.

The History and the field

The first dunk contest in major American professional basketball came at halftime of the ABA All-Star Game in Denver in 1976 at a time the league desperately needed eyeballs and pitted skywalkers David Thompson and Julius Erving against each other. Erving took the title after he dunked from the free-throw line.

The next year the NBA brought the dunk contest into existence, but in an even more odd format, pitting one player from each team in a series of one-on-one dunk competitions throughout the season until the title was determined in June. The Pacers' Darnell "Dr. Dunk" Hillman beat out Golden State's Larry McNeil for that title.

In 1984, the NBA found itself looking for a gimmick to get more eyes on the All-Star Game, also in Denver, and decided to pair the Dunk Contest with an old-timers' game to create a second night of action. It got an excellent first showing with then-Phoenix forward Larry Nance beating Erving in the finals. Erving dunked from the free-throw line again for a perfect 50, but he had some misses on his card already and Nance put the contest away with a windmill dunk that earned him a 47.

So in 1985, everyone who wanted to be considered a dunker wanted to be a part of it.

"At that time, the Slam Dunk Contest was at an all-time high," Wilkins said. "It was the event, the must-see event of All-Star weekend."

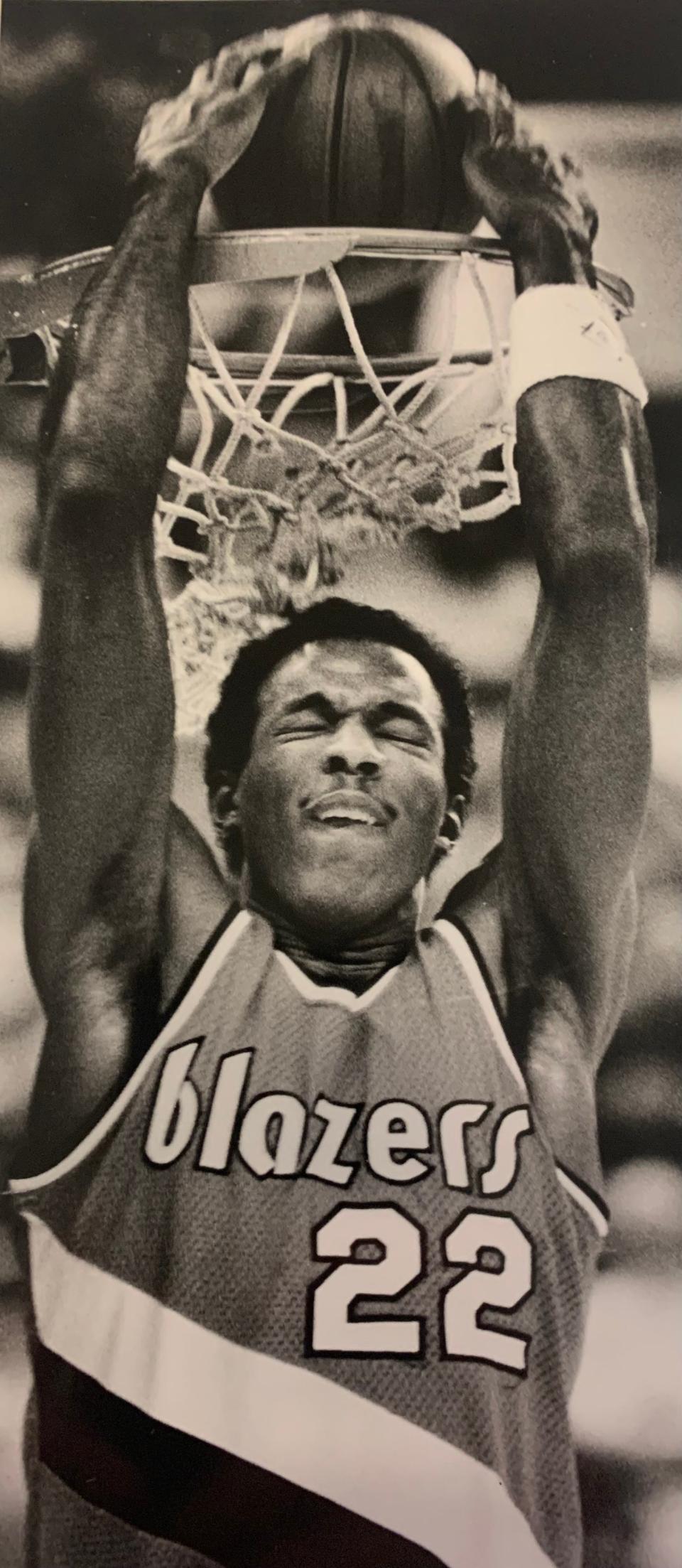

Nance and Erving came back for a second year. So did Wilkins, Utah's Darrell Griffith -- the former Louisville All-American known as "Dr. Dunkenstein" -- Portland's Clyde Drexler and Chicago's Orlando Woolridge.

"People don't know how great of dunkers those guys were," Wilkins said. "The athleticism that they displayed. Nobody talks about Larry Nance. Nobody talks about Darrell Griffith. Them guys were amazing. I was fortunate to be in the field with some of the highest flyers in history."

To fill out the field, the NBA's intention was to bring in new blood and it had commitments from two rookies who were turning heads in the league. One was Chicago's Michael Jordan, who had been named to the All-Star Game already and would go on to win Rookie of the Year honors. The other was Philadelphia's Charles Barkley, would be named All-Rookie. Barkley, though, was scratched due to injury and the NBA needed a replacement. They found one in Indianapolis who had never been in a dunk contest, but had a body and a background that prepared him for just such a moment.

The Tale of Terence Stansbury

Terence Stansbury was born in Wilmington, Del., and went to high school in Newark, but he spent one year in high school in Los Angeles when he was 16, and he'll never forget that year because that was when he learned how to dunk.

"That was the first time I made a high school team," Stansbury said. "During that year, for some reason, I grew like 7 inches and my vertical leap also went through the roof. So I was trying a bunch of dunks after practice with a couple of teammates."

One he tried was a simple concept, but it required astounding athleticism and it was visually spectacular. He leapt in the air off of one foot with the ball high in his right hand, spun around in a full 360-degree circle and dunked. He didn't have a name for it at the time, but when he returned home to Delaware to play at Newark High School, one of his friends knew exactly what to call it.

"A friend of mine saw me doing that and he said, 'What was that?'" Stansbury said. "I said, 'It's a one-legged 360.' He said, 'No, it looks like the Statue of Liberty. We're gonna call it the Statue of Liberty 360.'"

Stansbury didn't base his actual game around dunking, but messing around with dunks was a fun way for him to spend time with his friends on the playground and he was proud of his athleticism. He had his vertical leap measured at 43 inches before he started his college career at Temple, so he chose No. 43 as his number. In his first two years there, much of his scoring came off of dunks, but then coach John Chaney came along and helped him expand his game to include more jump shots. He scored 24.6 points per game as a junior, was Atlantic 10 Player of the Year as a senior and ended up being the No. 15 pick in the 1984 draft.

"I became a scorer and a thinking player," Stansbury said. "I was taught how to play basketball fundamental wise, the right way, with skill. I could jump fairly high, but dunking was not what people talked about at all. ... I still remember my coach teaching us, the game is played on the ground not in the air. I was a basketball player learning to play the game on the ground who also could fly through the air."

Stansbury had dunked enough at Temple and in games with the Pacers for it to be known that he had real athleticism, though, and even though he was coming off the bench for Pacers team that would finish 26-56 and had produced no All-Stars, he had no fear that he would be able to compete with even one of the strongest dunk contest fields of all-time.

"I thought I could dunk with anybody," Stansbury said. "I had a 43-inch vertical leap. I could dunk off one leg. I could dunk off two legs. I was kind of creative at the time. Most of those guys were doing basic dunks that everybody could do. But I thought I was one of the top five dunkers in the world."

And on that night anyway, he was right.

The First Round

Wilkins just missed the finals of the 1984 Slam Dunk Contest and a number of people told him he deserved to make it next to either Nance or Erving. He was in good position before Nance dunked with two balls and Wilkins received a harsh score on his final dunk. He drove baseline from the right corner, went underneath the bucket, leapt, turned and threw down a violent windmill dunk over the left side of the rim, but he got a score of just 33 and was eliminated.

Wilkins, however, didn't leave with any feeling that he'd been cheated.

"Actually for me, I didn't think I deserved to be in the finals that year," Wilkins said. "Because I was just in awe of Dr. J, and I didn't think I did that well in that first dunk contest. But it was a measuring stick for the next one, because I wasn't going in to just be a participant. I was going in to win it."

Erving and Nance got automatic byes to the semifinals with the remaining six battling for two spots. Wilkins got to dunk first, and he wanted to set the tone. It was a simple dunk -- he drove straight down from the top of the key, jumped off two feet and did a two-hand windmill. But as always, he did it with power, and the pure violence of the dunk seemed to wake everyone up. He registered a 47 right out of the gate.

"My dunks were angry," Wilkins said. "I could make a simple dunk look great because of how hard you dunked it. That's the way I played the game and I just took that to the dunk contest."

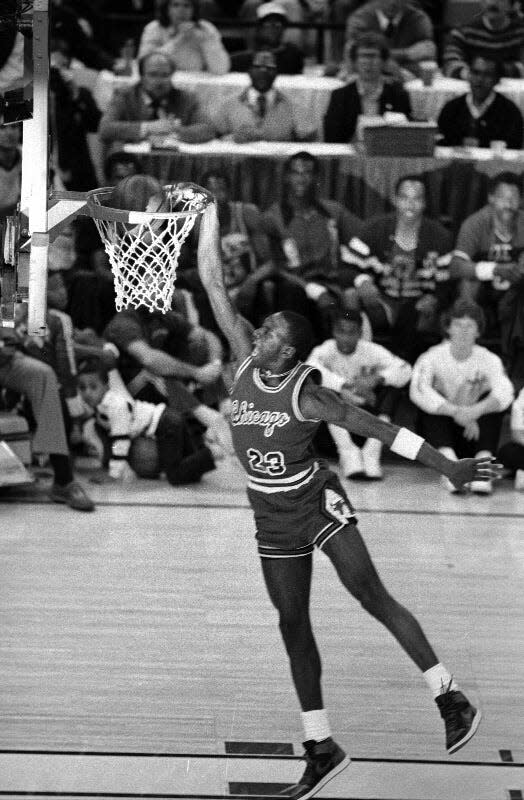

Jordan made a statement of his own with the way he was dressed. Each of the other participants dunked in their jerseys and game shorts. For the first round, Jordan wore black and red track pants and a red tank top over a black t-shirt with no sleeves and a gold chain. He was wearing Bulls colors but not a single Bulls logo.

It made everything he did look a little more effortless -- as though this was just a Saturday afternoon at the playground for him -- but he was no less effective. On his first dunk, he drove from the right elbow, crossed in front of the rim and turned so he was dunking over his back. He registered a cool 44 on the first dunk.

"I was looking for the best from him," Wilkins said. "Michael is the most fierce competitor that has ever played this game. I knew he was gonna bring it."

Stansbury took the floor to a sizable ovation from the Indianapolis crowd, but he registered a slightly disappointing 40 on his first dunk when he crossed in front of the rim, took the ball from his right hip to his left shoulder and then slammed. On his second attempt he pulled out his ace -- the Statue of Liberty 360. He executed it perfectly and scored the only perfect 50 in the first round.

"I had three dunks that I really wanted to do," Stansbury said. "I wanted to do my Statue of Liberty 360 before anyone else tried to do something like that."

The dunk put Stansbury ahead of Jordan at the moment, as he had posted a 44 on his second dunk also. Wilkins put the contest out of reach for both men, posting consecutive 49s on his second and third dunks -- a reverse in which he leapt in the air, brought the ball down to his waist and then slammed with two hands and a 360-degree tomahawk.

Jordan registered a 42 on his third dunk of the first round on a basic spinning dunk that wasn't quite a 360. All Stansbury needed was a 40 to tie him, but he wanted to go bigger. He tried a dunk from the free-throw line but fell short. Misses, however, didn't count as negatives. He then tried the second dunk he wanted to do, bouncing the ball off the floor to himself and catching in the midst of a 360.

"I heard guys talking about how they wanted to try that in the locker room before the dunk contest," Stansbury said. "They were afraid they might miss it and it would go against them. I thought, 'That's easy. I do that all the time with my friends on the playground.'"

He figured that was sure to get him to the next round, but the score that registered on the board was just a 34.

That didn't seem right.

"When I saw my score when I bounced the ball off the ground and walked into a 360 and caught it and dunked it and they gave me a 34," Stansbury said, "I said, 'Hold up, what the hell is this?'"

After an Orlando Woolridge dunk completed Round 1, however, officials determined that there had been a computer error on Stansbury's score. They determined he should have been tied with Jordan, and that they would settle the tie by giving each man one more dunk.

The Dunk-Off that decided nothing

Stansbury invited five of his hometown friends from Delaware who had been close to him for years and seen the things he could do on the playground. The group included his brother Lawrence, cousin Jerome Hicks and several of his friends. They got to sit courtside near the baseline, which was close enough that he could talk to them if he wanted to. And security at games wasn't what it is now, so there was not much preventing them from coming on the court.

"They had seen all my dunks in high school and they were saying, 'If you need something, just come to us,'" Stansbury said. "I said, 'Listen, at some point, I'm going to get you guys on national television.'"

And he did.

Stansbury won the coin flip for the dunk off and allowed Jordan -- who finally ditched his warm-ups in favor of his jersey -- to go first. Jordan's dunk was fairly spectacular, a rock-the-cradle dunk from the right side to the front of the rim which earned him a 40. So before the dunk that would give Stansbury a chance to eliminate the man who would become one of the greatest players in history, he ran down to their side of the floor for advice.

"I said, I'm going to get my Delaware crew a national audience," Stansbury said.

The analysts on the TV broadcast called them "his consultants" and one of them clearly suggested an emphatic reverse dunk. Stansbury obliged, driving with big loping strides from half court down the slot, taking off from the ride side of the paint and turning in mid air so his back was facing the basket and dunking over his head. Shortly after that the scoreboard registered a 46, meaning Stansbury would advance. He pumped both fists in the air, and Jordan shook his hand to congratulate him for moving on.

Seconds later, however, an NBA official informed the men that they would both be moving on to the semifinals, and that Jordan had not been eliminated. The semifinals would simply include five men instead of four.

"Everybody in the audience was more surprised than I was," Stansbury said. "I was like, 'OK, it's the NBA. Let's have a show. It doesn't matter.' I watched dunk contests. I'd seen that in the inner cities and they do things that way. But we never expected the NBA to change its rules that quickly."

The Semifinals

Stansbury's consultants didn't steer him wrong until his final dunk of the semifinals.

He went to his friends for advice in each of his first two dunks of the round and they paid off. The first time, while driving toward the bucket he touched his left hand to his right shoulder, looped the ball and his right hand underneath his left, flipped the ball in the air, caught it with both hands and dunked for a 49. The second time he brought the left hand to the right shoulder again and flipped the ball forward, grabbed it, reversed in the air and dunked the ball over his head for a 48.

But the last idea turned out to be a little too ambitious. He tried a 180 at the rim with a little too much motion at the top and he didn't quite finish it. After the miss, he opted for something more simple just to get the dunk completed and he ended up with a 39, which dragged him down just a little too much to make the finals.

"My brother told me to look to the crowd and do a reverse dunk," Stansbury said. "I got to the point and then I missed the dunk. Because I was allowed to have the next dunk, I didn't know what to do, so I did a basic dunk and got a low score. I was blocked at that time. I had more dunks, I just didn't know. I guess I fell into the pressure a little bit or some people may say."

The 39 effectively took Stansbury right out of contention. Wilkins simply kept going like a machine, throwing down a two-handed windmill for a 48, a ferocious 360 tomahawk for a 45 and then a quarter turn when he brought the ball down to his waist again and slammed for a 47.

Jordan turned his game up with each dunk, posting a 45 on a one-handed reverse, a 47 on another half-spin, and then a 50 on a dunk from the free-throw line. The defending champion Nance and the elder statesmen Erving had some moments, but couldn't quite compete with that and the first Wilkins-Jordan duel was on.

But Stansbury got one more moment of glory before he left the floor. He and Wilkins did an interview on the Turner broadcast with the great Bill Russell, who told Stansbury the State of Liberty 360 was "as beautiful of a thing as I've ever seen anywhere. That was just outstanding."

The Finals

Wilkins said he didn't enter the contest with much in the way of strategy, but one thing he did know is that when he got to the finals, he wanted to put the rookie Jordan on the spot if he got an opportunity. So when he won the coin toss it was an easy decision to make Jordan go first.

"Usually I would go first," Wilkins said. "But I let him go first just to see what he would do, then I could dictate what type of dunk I could do on my behalf."

Jordan's first dunk wasn't one of his best, something fairly basic that earned him a 43. That put Wilkins in position to take an early lead and keep it. He did, driving baseline from right to left for a reverse slam, starting the finish before his head had passed under the net for a 47.

Jordan answered by bouncing the ball to himself for another reverse dunk for a 44, but Wilkins effectively put the contest away with a 50, bouncing the ball off the floor, then off the glass, catching the ball while in mid-jump, bringing it down to his waist and then twisting into a reverse dunk.

"That is just all timing," Wilkins said. "It gotta be just right. Then once you get in the air, you do the rest. The bounce has to be right, the throw off the glass has to be right where you can catch and feel comfortable making a great play."

Jordan had one more answer, a spectacular reverse cradle that earned him a 49, but Wilkins didn't need to do much to win and he did plenty, throwing down one more two-handed windmill for a second 50 to take the title.

"I had to have a great dunk for the fans," Wilkins said. "It wasn't about me. I wanted to do it for the fans. I wanted to end it on a really nice dunk."

The Epilogue

The 1985 dunk contest was in a way the start of the event's golden age. Jordan sat out the next year with injury, but Wilkins' 5-7 teammate Spud Webb stole the show with his improbable 1986 victory. Then Wilkins and Jordan dueled again in 1987 and 1988. Jordan won both but Wilkins kept him at the top of his game, as Jordan's 1988 victory on the double-pump dunk from the free-throw line helped sell thousands of shoes and posters.

"You had two great players going head to head," Wilkins said. "You don't see that anymore."

Stansbury would call his performance in the event a "blessing and a curse." He participated in the next two dunk contests after 1985 and finished third in each of them. He started to develop a reputation as a dunker and felt that's all his coaches wanted him to do.

"People stopped looking at me as a player around the league and started looking at me as a dunker," Stansbury said. "... Right after that dunk contests, people just wanted to see dunks, they weren't looking for jump shots and assists and those kinds of things. George Irvine, our coach at the time, he kinda looked at me differently also. It was kinda strange being the only guy on that team with all those nice players representing the team. At the time my role was kinda the seventh man, trying to be the sixth and then trying to be the starter. ... A lot of the attention that I got after the All-Star Game was about dunking."

Stansbury played just two more seasons in the NBA, including one with the Seattle Supersonics, before leaving to play in Europe. Former Villanova coach Rollie Massimino got him contacts in Belgium. He had to spend some time as an amateur before the rules changed in 1992 to allow professionals to participate in international competition such as the Olympics and he turned down several short-time NBA offers to stay, and then he turned down more serious ones because he'd decided he liked the lifestyle and style of play. He spent 16 years playing professionally in Europe before he retired and got into coaching there. He's been part of the development of French basketball, and his youth development program had a part in bringing up Victor Wembanyama and Bilal Coulibaly. He still lives in France.

"I had a better quality of life and had a great experience and became a much, much better player and discovered myself as a person," Stansbury said. "It was a wonderful experience."

Stansbury obviously didn't have the long-term career that Hall of Famers Jordan and Wilkins did, but his underdog contribution is still a big part of what makes the 1985 Dunk Contest a special one.

"The fact that they're still talking about it more than 30 years later," Wilkins said, "tells you it's one of the best dunk contests ever."

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: 1985 Slam Dunk Contest: Dominique Wilkins vs. Michael Jordan