Jerry Sloan was a throwback who defined the Utah Jazz

You could hear it in Karl Malone’s voice, the gravity of the moment when he interrupted the recent reunion of ’90s NBA stars to update them on his longtime coach.

“Coach Sloan isn’t doing well,” Malone said, asking for prayers that turned the laughs and lighthearted storytelling into a respectful silence.

Jerry Sloan coached only Malone and John Stockton among those on the call, but they all seemed to react with the same feelings, as if he were their coach. Sloan seemed to epitomize strength on the sidelines, a sense of control while having command of the consistent Utah Jazz for over two decades.

Sloan died Friday at 78. He battled Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia, which didn’t feel like a proper ending for Sloan. His public appearances dwindled over the last few years, and on the rare occasion he made it to a Jazz game, it was apparent his strength was sapped.

But his stamp on the Salt Lake City community and that franchise endured well beyond his 23-year run. Stockton and Malone are defined by each other as much as they are individually. It’s hard to bring up one without the other. It was Sloan, though, who defined everything the duo stood for. The pick-and-roll that became such a staple was unlocked by the hard-nosed defensive player who would’ve loved disrupting the rhythm of it as much as he was pleased by watching it executed properly.

It almost didn’t seem like it fit until you really watched Stockton and Malone play in the trenches. Malone threw borderline dirty elbows to unsuspecting guards coming down the lane. Stockton set some of the hardest picks on the baseline to free up Malone in the post on the rare occasion the point guard wasn’t setting up Malone from the top.

Sloan didn’t instill that toughness, nor could he be held responsible when Malone went over the line. But he fostered a culture that was going to be followed to the letter, and he was the main factor in the Jazz being known as a team that you’d have to beat if you wanted to thrive in the wild, wild Western Conference of the ’90s.

From 1990, Sloan’s first full season in Utah, to 2001, the Jazz hit the 50-win mark 10 times and were on pace to do it again in the 50-game, lockout-shortened 1999 season.

Sloan didn’t have the stories of, say, Paul Silas, a man who’s become legendary in NBA circles because he would challenge his players on the floor or in the locker room and would often back up those words.

Sloan was so tough, you wouldn’t even dare to challenge him.

Even Chris Webber learned Sloan wouldn’t hesitate to fight to protect his players if the coach felt something was over the line. Webber once set a hard pick on Stockton during a playoff game that drew Sloan’s ire — and it could have had consequences.

“Damn right, I want some,” Sloan yelled to Webber after Webber barked at him.

Realizing a coach would actually fight put the possibility in Webber’s mind: I could actually lose a fight to Jerry Sloan.

Who knows what would’ve happened in the imaginary scenario, but the then-57-year-old coach had just enough old-man strength to make you think.

It was simple: There was no backdown in Sloan.

He defined Chicago Bulls basketball in the era before Michael Jordan arrived for a team that wasn’t talented enough to win big but tough enough to leave you bruised.

Between 1966-67 and 1974-75, Sloan didn’t average fewer than 6.9 rebounds per game, with a high of 9.1 in ’66-67 — and he was a lithe 6-foot-5. Sloan and backcourt mate Norm Van Lier made life miserable for opposing guards, knocking them around the perimeter.

“If you ever got down the lane, you came away with scars,” longtime NBA analyst and former coach Hubie Brown said once during a playoff game. “That backcourt wasn’t bad.”

With that type of playing record, there’s no way his players could perform with anything less than maximum effort. Do you want to have to answer to a man who made a living among the trees to grab rebounds instead of waiting for outlet passes?

Not winning a championship didn’t haunt Sloan as a player or coach. Getting the Jazz to the Finals in 1997 and ’98 presented the challenge of going against Jordan at his most determined.

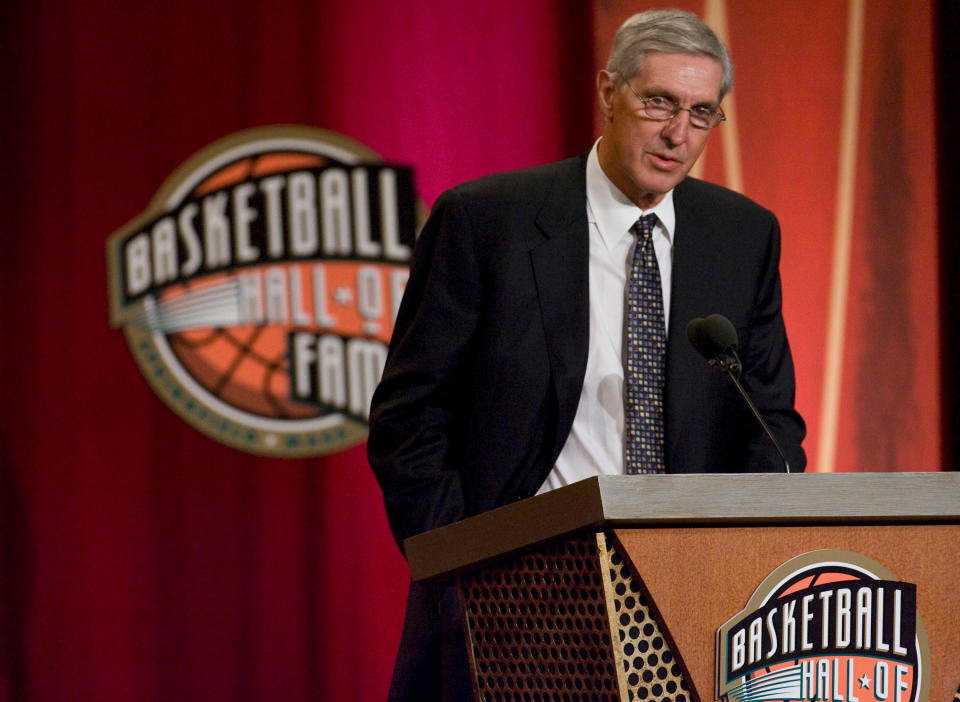

He didn’t have the horses to get him over the top, so he was never blamed the way other coaches were during that time. When he made the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame a decade ago, he still looked like he could go a few rounds.

Perhaps that’s why Malone’s words stopped everyone in their tracks over the weekend. Not because Sloan was losing the fight to Parkinson’s and other ills.

They were probably just shocked any disease had the moxie to step in the ring with a man who would never back down, no matter how old he was.

More from Yahoo Sports: