A pipeline of minority offensive coaches exists, but will NFL owners, GMs do their part?

ATLANTA — They came in search of knowledge.

In search of advice.

In search of a network.

Most of all, these men of color came to be seen.

And, collectively, they continue to shatter the notion that men like them — offensive coaches from the college ranks to NFL assistants — are not qualified to be head coach, offensive coordinators and quarterback coaches in the league.

The absence of men of color in top offensive coaching positions has permeated NFL hiring practices for far too long, and it is an excuse that NFL, XFL and college coaches and executives aimed to debunk this week at the NFL and Black College Football Hall of Fame’s inaugural Quarterback Coaching Summit in Atlanta.

Some of the most respected voices, teachers and trailblazers in football — among them Ozzie Newsome, Doug Williams, Urban Meyer, Rick Spielman, Jim Caldwell and Jimmy Raye — took part in the two-day event that featured panel discussions, presentations and unfiltered dialogue about the dearth of minority quarterback coaches and offensive coordinators in the NFL.

The purpose of the event was to share philosophies, experiences and the tools needed to climb the coaching ranks. And to show that a pipeline of talented minority coaches does in fact exist, NFL executive vice president of football operations Troy Vincent told a handful of reporters Monday night.

But what good is a pipeline if NFL owners and general managers aren’t looking to expand their circle of interest to include more applicants of color?

When the Minnesota Vikings began their last head-coaching search five years ago, “the majority of the minorities were on the defensive side,” said Spielman, the team’s general manager, during a panel discussion with current and former NFL GMs and executives. “Every coach that we interviewed, I couldn’t find one minority at the time, I don’t believe, that was going to get interviewed because there was a lack of minorities on the offensive side of the ball. And I think that’s where the issue is.

"Until decision-makers start making a concerted effort to start hiring people of color or women — ‘cause that’s coming as well — on the offensive side of the ball to make it an even playing field, that’s when, hopefully, you’ll see some breakthrough in that area.”

In the copycat world of the NFL, the annual rush to find the next best thing leaves teams desperate to ride the next big wave. This past offseason was no different, as offensive gurus and “quarterback whisperers” like Oklahoma’s Lincoln Riley, Texas Tech’s Kliff Kingsbury and ex-Miami Dolphins head coach Adam Gase became the object of the league’s affection. But when a good number of general managers, personnel executives and scouts were asked by Yahoo Sports earlier this offseason to name an up-and-coming offensive college coach of color, many were left speechless. As they say, ignorance is bliss. But knowledge carries with it a responsibility of action.

“This book, these names, will go back to Baltimore,” Newsome told the audience, holding up the booklet listing all of the names and photographs of the college coaches in attendance. “ … I didn’t know that there were this many African Americans involved in coaching quarterbacks and offensive coordinators on the college level. Now I do. Now I can act on it.

“ … So when I’m talking to another club, with another GM, then I can start to mention names. Because I’ve got some names. This book is going back to Baltimore. I’ve got names now… I’ve got me a Bible.”

‘Systematic’ problems impacting coaches of color

While the NFL has seen a rise in black quarterbacks, there are only two black offensive coordinators in the league: Eric Bieniemy (Kansas City) and Byron Leftwich (Tampa Bay).

Currently, there is only one black GM in the NFL: Chris Grier (Miami Dolphins).

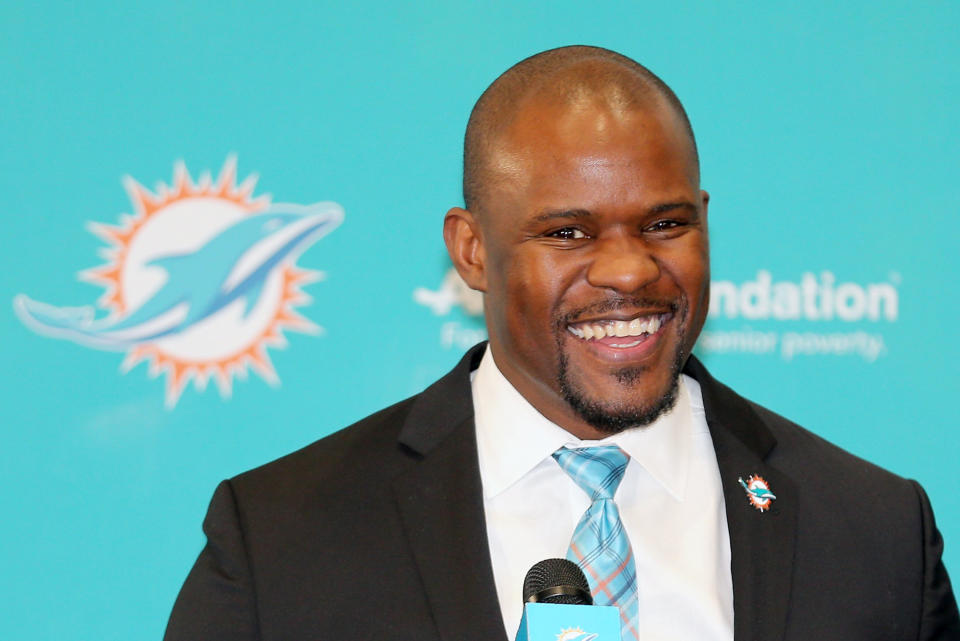

And there are now four head coaches of color: Anthony Lynn (Los Angeles), Mike Tomlin (Pittsburgh), Ron Rivera (Carolina) and Brian Flores (Miami).

But those paltry numbers don’t reflect the number of talented candidates of color within the NFL’s reach.

The assumption that black offensive gurus don’t exist is simply not true. And neither is the misguided belief that NFL hires are based solely on meritocracy (i.e., “If he’s a good enough coach, he’ll get the job.”).

Yet there is a danger in wallowing in the double standards. The unfairness. The progress that is slow to come.

Participants and presenters reiterated a familiar refrain over the two-day event: No one here is looking for a handout.

“I don’t want to be hired to be a feel-good story,” Kansas City Chiefs offensive coordinator Eric Bieniemy told Yahoo Sports, five months after he was passed over for multiple head-coaching positions during a hiring cycle that resulted in eight vacancies and only one minority hire (Flores). “I want to be hired because I’m the best man for the job.”

But the criteria and requirements that NFL teams use to identify and vet prospective candidates can be arbitrary and downright questionable. While a lack of head-coaching experience and NFL play-calling duties were used to cross off Bieniemy from team wishlists (See: the New York Jets and Cleveland Browns), similar shortcomings weren’t viewed as red flags in the cases of Matt LaFleur (the Green Bay Packers’ first-time head coach), Kliff Kingsbury (whose 35-40 college coaching record didn’t dissuade Arizona from taking a chance) and Zac Taylor (whose proximity to Sean McVay last season in Los Angeles made him more attractive to Cincinnati).

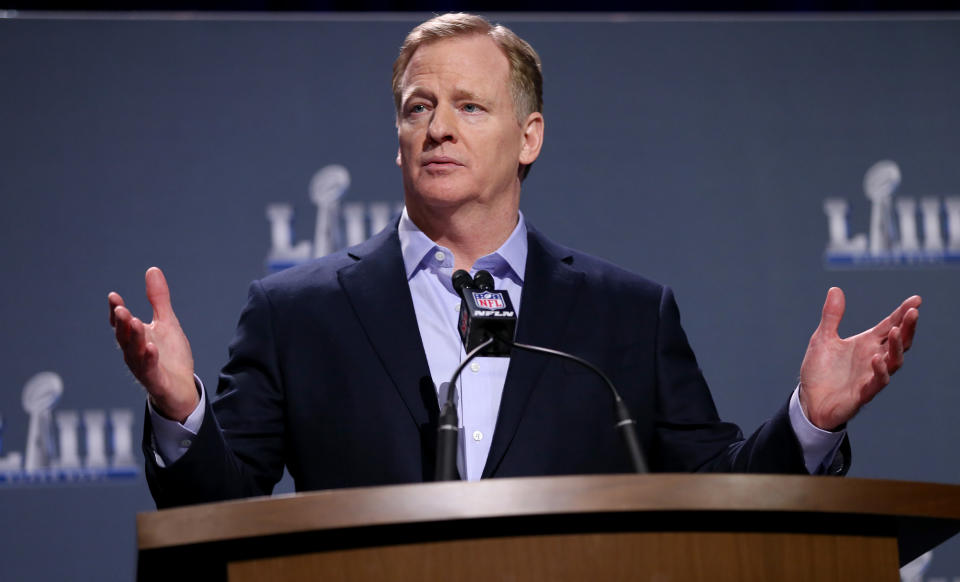

“I can sell a non-winning white [coach], but the challenge we have is trying to sell a winning black coach,” said Vincent, citing the past success of men like Caldwell, a respected, longtime coach who received only one interview this hiring cycle, and Jerry Reese, who won two Super Bowls as the New York Giants GM, being discounted by teams.

Vincent and others stressed the “systematic” issues that have given rise to the discrepancies between the standards used to evaluate and the second chances given to white vs. minority offensive coaches and personnel executives.

To help combat the uneven playing field, Urban Meyer encouraged the college assistants “to be very clear and intentional” about career aspirations with their respective head coaches.

“You get one swing. Be prepared,” said Meyer, the only white panelist besides Spielman. “ … Be great at what you do. … You want to be that quarterback coach? Don’t let them ask that question — you answer the question before it’s time.

But Meyer also acknowledged that interview requests for minority candidates don’t always feel legitimate: “It upset me very much when Charlie Strong was my D-coordinator down in Florida and he became the token minority guy, and I got so pissed. … Charlie Strong is one of the best I’ve ever been around.”

Will NFL’s power brokers implement change?

Workshops like the Quarterback Coaching Summit give long-overdue exposure to an often-overlooked segment of the coaching landscape. But many of these intelligent, gifted tacticians won’t be considered for opportunities they’re actually qualified for unless NFL executives operate with diversity in mind.

Williams, the first black quarterback to win a Super Bowl, offered a simple, yet poignant observation at the conclusion of the summit: “What can be done, could be done, if given the opportunity.”

Those with the power to affect change — owners, general managers and personnel executives — are complicit in the current disparity in the NFL ecosystem.

Oftentimes, they do what’s easiest and expected. But it takes far more effort to tread unfamiliar territory, to go against the grain and to take a chance on a talented, yet perhaps inexperienced person of color. But if the NFL is committed to diversity and inclusion as it purports itself to be, teams will actively and genuinely take advantage of the pipeline of minority offensive coaches.

“Our ownership group is a strong believer in diversity,” Spielman said. “And they created two quality control positions on the offensive side this year. And I told Coach [Mike] Zimmer and ownership that both of those are going to be filled with minorities.

“It’s easy to go out and find white people to fill those, to be honest with you,” Spielman added. “But to go out and find diversity on the offensive side of the ball, we did a nationwide search … but found two top-quality [candidates] that were actually GAs at the collegiate level, that played college football.”

Monday’s panels gave way to presentations of personal testimonies, interview techniques, offensive philosophies and schematic breakdowns during Day 2’s session at Morehouse College.

“To hear these men come up here and deliver the way you did … God dammit, we know this game,” said Vincent, addressing the room. “We can coach it. We can teach it. We can light that scoreboard up. And we can stop people defensively. We know how to identify talent. We’re just asking for a more fair process.”

Many in attendance expressed confusion over Bieniemy not being hired as a head coach, but the Kansas City coordinator expressed only gratitude for his opportunities to interview during a one-on-one interview. He also acknowledged that he did some self-scouting in order to better prepare himself for the next wave of offseason interviews.

“There are certain things that stand out, and you say, ‘Hey, you know what? I could have been better,’” Bieniemy told Yahoo Sports. “But I will say this: After going through that process, and if I’m blessed and fortunate to have that opportunity again, I’m good. I’m ready.”

More from Yahoo Sports: