It sure seems NBA fans aren’t ready to hear Kyrie Irving’s truth

A weekly dive into the NBA’s hottest topics.

We’re mad because Kyrie Irving is telling on us

Forget for a moment that 18,000 people screaming in unison at one person who is sometimes separated from them by only a few feet is something we consider normal, and consider the fact that by just bringing up the idea that, hey, maybe this shouldn’t be normal, Kyrie Irving engendered vitriol from more than just Celtics fans.

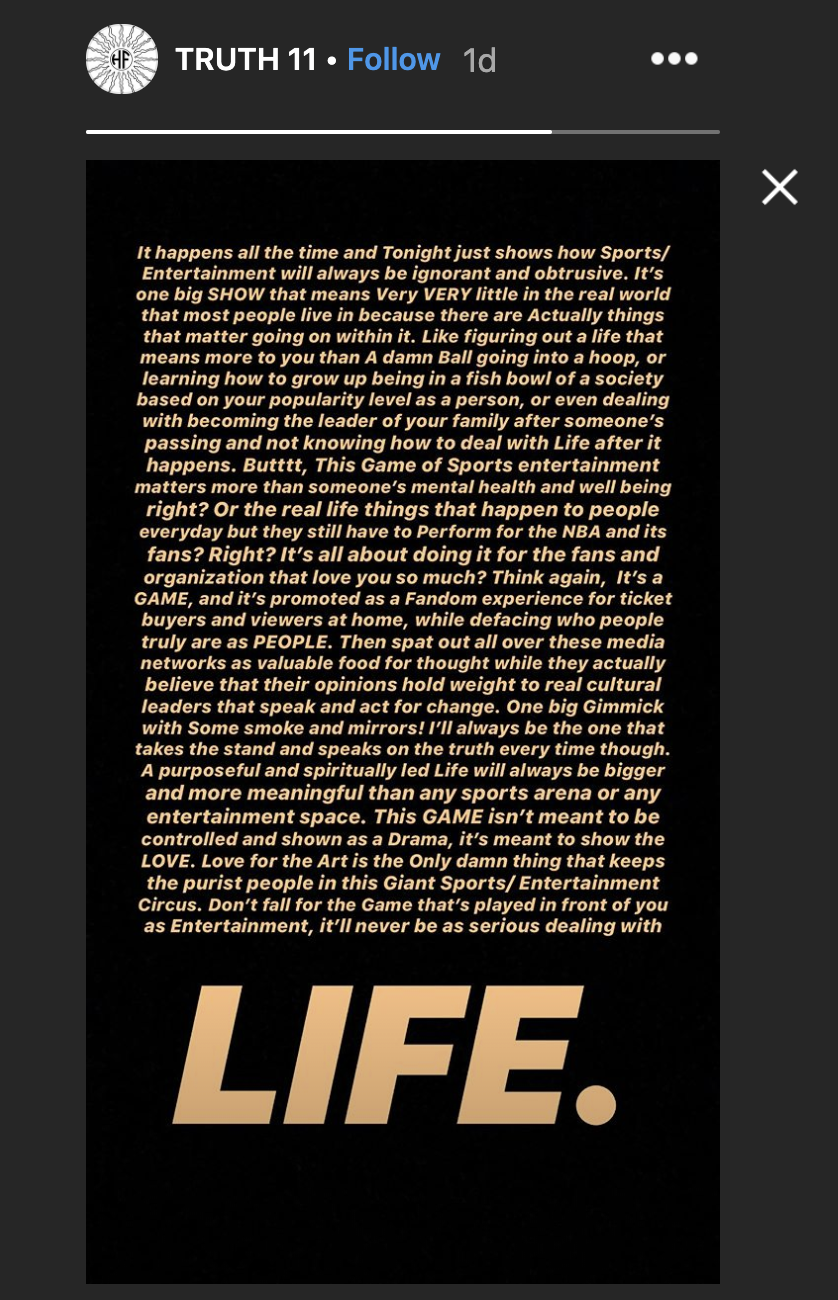

That’s what happened to Irving on Wednesday night, when his absence in his return to the TD Garden with the Brooklyn Nets didn’t stop fans from taunting him. At one point, a “Where is Kyrie?” chant broke out. Irving, who has missed the last seven games — including the Nets’ home win over the Celtics on Friday — with a shoulder injury, took to Instagram to respond:

None of what comes next is to excuse some of Irving’s most annoying, inconsiderate antics: not taking five minutes to autograph basketballs for charity, telling a production crew to photoshop his hat out of a team picture instead of just taking it off. One time, he even changed his mind. He is an imperfect messenger of a message that pillories NBA fans and media, but I’m not here to analyze Irving’s character. The irony is that, despite his fame, few people are qualified to talk about that. I’m here to talk about the reaction to a post that is, third-eye asides aside, true: NBA stars live in a fishbowl, where fans poke and prod at them and demand no reaction in return. If you think he would have been treated any differently if he had behaved better, by the way, consider how Pelicans fans treated Anthony Davis, who was a perfect citizen before he demanded a trade.

The response to Irving’s Instagram story, for the most part? That’s what the money is for. If you haven’t seen Mad Men, Don Draper is usually not the guy whose outlook on life you want to find yourself agreeing with. The attitude prevails within the NBA, too. Stars aren’t just paid for being good at basketball. They’re paid for being good despite the noise, because the noise rakes in profit. The underlying message, despite all the hubbub about caring about players’ mental health, proves Irving’s point: A good deal of an athlete’s monetary value lies in how well he or she handles mass bullying. They are rewarded with two things that through cliché and anecdotal evidence and clinical study have been proven to be hollow — money and fame — although nobody wants to factor that into the argument when they find out a celebrity is unhappy. Truly internalizing that would admit that we are all chasing the wrong things. It’s way easier to just get mad at strangers for being unhappy out loud.

The NBA has made mental health an increasing priority, and fans have applauded the league for it, but they have only applauded players who have opened up with clean, ultimately feel-good stories: thought-out, edited Players Tribune-style essays that are reflective, which is to say, opening up about a past that they have overcome, not a present that has ramifications for people they are around, most importantly the win total of the team they play for.

The more Irving is criticized for lashing out, the more it’s clear that he’s right about the dehumanization of athletes: most people really don’t give a damn about anything except for how well they are playing. Irving touched on the point in his opening press conference with the Nets, when he opened up about how the death of his grandfather impacted his behavior in his final season with the Celtics, and the forces that insulated him from his grief in order to ensure he kept getting buckets. “I barely got a chance to talk to my grandfather before he passed, from playing basketball,” he said. “So you tell me if you would want to go to work every single day knowing that you just lost somebody close to you doing a job, every single day that everyone from the outside or anyone internally is protecting you for. Like, ‘Hey, just keep being a basketball player.’ ” Earlier in the press conference, Irving discussed the pressure his teammate, Kevin Durant, faced to return to the court during the NBA Finals, ultimately resulting in a torn Achilles injury that will rip a year from Durant’s career.

You can understand how Irving might have an ambivalent relationship with the circus of the NBA and the fans who would prefer it if the performers smiled more. He’s not the only one. As commissioner Adam Silver addressed last March, “a lot of players are unhappy.” Most players are willing to play the game within the game, paying lip service to “the world’s greatest fans” who “give them energy every night,” all the while wondering why so many strangers feel a weird sense of ownership over them.

Irving, on the other hand, makes us look at the thing we hate: when famous people show us what fame does. To people. Because however minuscule our individual impact, it makes us feel just a little bit guilty, just a little bit gross. And then we think, “Well, that’s not my fault, I’m one person!” and, “Hey, Kyrie, could you not hold the mirror up so close to my face?”

Irving is begging for mercy from a public that utterly refuses to give it. And maybe he doesn’t deserve our empathy. Where you fall on that issue probably depends on whether you believe it’s a finite resource. Who knows? Either way, if Irving is deflecting, so are we, and if he asked for it, so did we.

The sinking banana boat

On Wednesday night, Chris Paul weaved the ball through his legs, stepped back and unfurled a jump shot over Carmelo Anthony’s outstretched hand in a moment that would have been routine if not for the jerseys on their backs. Paul, traded from the Houston Rockets this offseason, plays for the rebuilding Oklahoma City Thunder, while Carmelo Anthony got his perhaps final shot in the NBA with the Portland Trail Blazers last week.

It occurred to me then that no matter how good you are, unless you’re LeBron James — who was minutes away that night from taking the floor with Anthony Davis to play the Pelicans, whose fans mercilessly booed them for forcefully engineering this marriage — you can’t control your history. History merely happens to you. Even the final leg of the banana boat, Dwyane Wade, only rode off into the sunset in his idyllic final season with the Miami Heat because he was with a world-class organization. Only LeBron truly beat his NBA circumstances, dragging himself out of the Cavaliers’ muck long enough to learn how to win and return his hometown to glory.

Paul and Anthony are still kicking around, hungry for a ring. There was a time it was hard to imagine Paul not eventually winning it all, when his constant string of second-round outs were considered bad luck, not instructive. He was so smart, so hungry, so talented — considered the best captain to steer the ship. Until the Golden State Warriors’ chaos-happy, 3-and-gun style swept the league, punishing the predictability of Paul’s iron grip on the basketball.

Paul’s inability to cede control did him in, but he didn’t really have a choice in the matter. Great players, Melo’s career arc will tell you, never really change. You’re either suited for the environment around you or you’re not, and when Paul had his shots at rings, the NBA was no longer suited for control. Paul was a few years too late to the game to be valorized, and now he’s somehow in the same position as Anthony, whose decisions never skewed so much toward winning as they did toward living an enjoyable life in New York and making a ton of money.

Toward the end of his career, the man that has always been in command is playing hard but he’s playing for nothing, hoping some contender trades for him, his final shot at victory in somebody else’s hands. But I guess that’s the way it’s always been.

Showtime is back … and it’s the new Lob City?

The Los Angeles Lakers do a great job of something nobody else does anymore: getting points in the paint by actually being in the paint. While most teams play outside-in, using the threat of the 3-point shot to penetrate the paint, the Lakers are last in the league in drives per game, but they lead the NBA in paint touches and are second in post-ups. Anthony Davis posts up more than any player in the league not named Joel Embiid.

All of this sounds pretty boring, right? It’s not, because they own the paint by throwing the ball higher than anyone else. With 39, the Lakers lead the league in completed alley-oops by a mile. To put it in perspective, the Rockets are in second place with 29. The 2011-2012 Clippers, a team nicknamed after lobs, notched 107 alley-oops all season. Right now, the Lakers are only eighteen games in.

With the towering length of JaVale McGee, Dwight Howard and Davis in tow (not to mention LeBron’s athleticism), one of the most surefire ways the Lakers generate points is by throwing the ball in the general direction of the rim and hoping everything goes well. Sometimes, the recipient of the lob will tap riskier passes back to the guy who made the pass. With the attention of the defense directed toward the rim, the player with the ball in his hands usually has an open look smack-dab in the middle of the paint. I’ve seen it happen enough times now that I wonder if it’s ever being done on purpose. Innovative success becomes regularized, and in time, leads to something else — I’ve never seen a double alley-oop in a halfcourt setting before. We might get one this season.

More from Yahoo Sports: