Who invented the point forward? Coaches and players from Wisconsin and Milwaukee played a part

“When we say point forward, it means that he’s going to flop with the two guard.” – Milwaukee Bucks head coach Don Nelson on Paul Pressey in 1984

In a Milwaukee Journal story published Nov. 6, 1984, Don Nelson made the first public reference of a new hybrid position – point forward – in the NBA, one that would fundamentally change the game.

But who invented it? Who played it first? Who named it?

Those answers vary, depending on whom you ask. What is definitive, however, is that a collection of coaches and players in and from Milwaukee and Wisconsin were part of them, which pushed the NBA into a new era in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And it is only fitting that four decades later Giannis Antetokounmpo would surpass what most imagined a forward could do with the ball.

In a two-part series, the Journal Sentinel interviewed two dozen players and coaches to examine the origins of the point forward position and how it's rooted in Wisconsin – even if its seeds flowered around the country. In Part 2, Antetokounmpo will show how he has perhaps pushed the point forward to near extinction and the league into a new era of position-less basketball.

Tom Nissalke needed to innovate in Houston

In 1976, Wayland Academy and University of Wisconsin alumnus Ray Patterson tabbed an old friend and pupil in Tom Nissalke to turn around the Houston Rockets.

Their history ran deep, as Patterson first coached Nissalke at the Beaver Dam high school. Patterson then started Nissalke’s career by hiring him to coach their high school alma mater. After Nissalke had brief stints as an assistant at Wisconsin and Tulane, he joined Larry Costello’s coaching staff with the Milwaukee Bucks in 1968 when Patterson was the president and GM.

Following the Bucks’ championship season in 1971, Nissalke, a Madison native, began the itinerant life of a professional basketball coach. Patterson took over as GM of the Rockets in 1972 and, after missing the playoffs three times in four years, he hired Nissalke to make the Rockets consistent winners.

But, he was not exactly known as an offensive innovator; the hard-nosed Wisconsinite's calling card was defense.

And in his first season, Nissalke won coach of the year after guiding the Rockets to the Eastern Conference finals by making them a top-10 defensive team. But after his second season, the Rockets offense cratered to the bottom of the NBA.

So to start 1978-79, Patterson swung big and signed free agent Rick Barry from Golden State to juice the offense. Placing Barry alongside point guard John Lucas, all-stars Moses Malone and Rudy Tomjanovich and scoring guard Calvin Murphy would create a dynamic offense.

Or so Patterson and Nissalke thought.

In that era, true unrestricted free agency did not exist. Compensation was required if a team signed another team’s free agent, but the Rockets and Warriors could not agree on that. So, the decision fell to NBA commissioner Larry O’Brien.

To the shock and dismay of the Rockets, O’Brien sent the 25-year-old Lucas to Golden State.

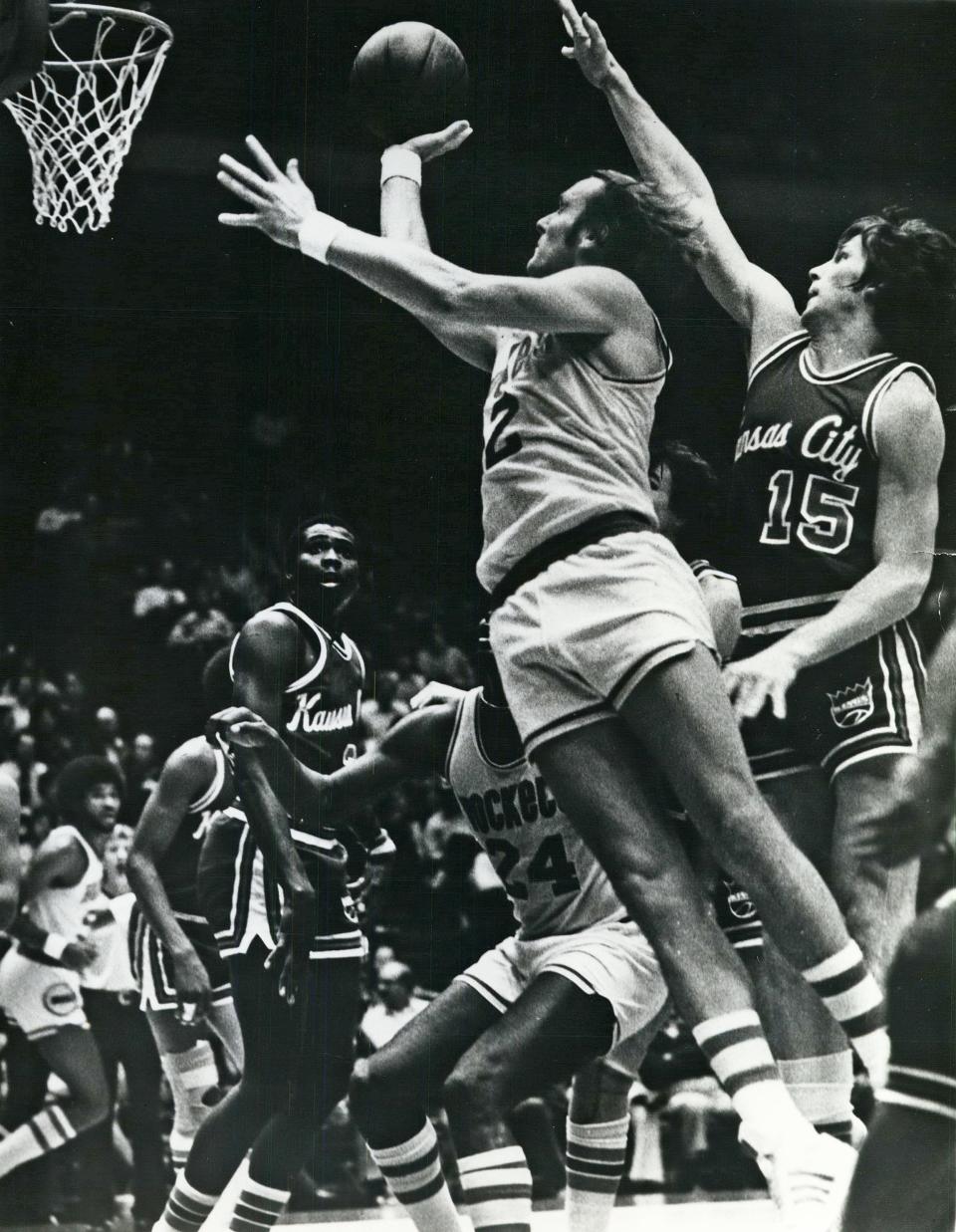

Suddenly, Houston didn’t have a point guard. Nissalke had to improvise, and he eventually turned to Barry.

Though the forward averaged 6.0 assists per game with Golden State from 1973-78, the playmaking was a result of the attention on him as an elite scorer. This would be different.

The 6-foot-7 Barry would be setting up the Houston offense.

“I was probably the first one,” Barry said of the concept of point forward. “There were very few times that you saw forwards in the top 10 in assists. I’ll do whatever it takes to win and that’s what it really was basically all about.”

He averaged a career-high 6.3 assists, sixth-best in the league. He had 28 games of at least seven assists, including 11 with 10 or more.

“It was just to utilize his great passing skills and also to get the great shooters in position,” said Del Harris, Nissalke’s assistant coach. “And Rick could score it, he could drive it, he could pass it inside to Moses or he could find shooters coming off the screens.”

The experiment, and Barry, were derided in real time.

“He is content now to take an occasional shot, play inconsistent defense and pretend he's a 6-foot-7 playmaking forward,” wrote the Washington Post in December 1977. “He’d rather stand at the top of the foul line and pass (he's averaging seven assists) than try to penetrate down the lane.”

The Rockets offense drastically improved and they finished fifth in scoring but were swept out of the playoffs. Nissalke was fired.

“They talk about all that as a wonderful thing,” Barry said of Nissalke's decision to have him run the offense.

He laughed incredulously.

“No, what it did was shorten my career," Barry continued. "I was the only forward in the top 10 in assists and everything, but I didn’t get to shoot the ball, so they basically made me just the afterthought for offense. Which was fine, I just wanted to win. But I didn’t go there with the intention of wanting to be that way."

Even if the idea of a bigger playmaker wasn't accepted in that moment, Del Harris definitely took to it. So when he assumed the Rockets head coaching job in 1979-80, he didn't abandon the concept. Instead, he leaned into it with 6-8 forward Robert Reid.

“I would often start at small forward and then five, six minutes into the game I went to the point guard and had that transition,” Reid said.

In 1980-81, Reid averaged 4.2 assists as the Rockets made it to the NBA Finals.

“Rick and Robert, typically, they were going to be more mobile than the guys they played against,” Rockets shooting guard Mike Dunleavy said. “Robert, he was really framing us up as shooters for sure.

"Rick is one of the greatest passing forwards of all time. So, for him to break down everything and create a play and open it up for us, it was a clear and good strategy.”

A Milwaukee star helps Seattle win a title

John Johnson led Messmer High School to a state title in 1966 and was an All-American at the University of Iowa, but it was clear he was more than just a scorer.

"He was a big forward who could really handle the ball, shoot well, rebound, drive to the basket," former Milwaukee Don Bosco coach Tom Sager said in a 2005 Journal Sentinel story.

The first pick of the expansion Cleveland Cavaliers in 1970, the 6-7 Johnson burst into the NBA with consecutive all-star seasons, averaging 16.8 points and 5.0 assists. But he was traded to Portland in 1973 and Houston in 1975, where he would later play under Nissalke.

“I did learn a lot from him and saw he was able to handle the ball,” Reid said of Johnson. “And that’s how I was able to do it.”

When Johnson was traded again, this time to Seattle in 1977, it looked like he was closer to wrapping up his career than revitalizing it. As luck would have it for him, the SuperSonics fired head coach Bob Hopkins in-season and hired Johnson's former Cavaliers teammate Lenny Wilkens.

“His skill set stood out to me,” Wilkens said of Johnson. “Either one of us got the ball, the other would take off and I thought, hey, this is great, this makes us much more effective. And I thought it was something that wasn’t utilized in the NBA hardly at all at the time.”

Wilkens expanded Johnson’s playmaking role in 1978-79, helping the SuperSonics win their only NBA title. Johnson often looked like the playmaking wunderkind from Messmer, as he averaged a team-high 4.4 assists.

“’J.J.’ brought the ball down and got everybody in the play,” Reid said. “They kept listing J.J. as a forward but he’d let Freddy Brown and (Gus) Williams (rest). They had strong legs come the fourth quarter because they didn’t have to handle the ball as much.”

In 1980 Johnson averaged a career-high 5.2 assists.

“He was very good at making the play and passing the ball and loved doing it,” Wilkens said. “I just felt like, hey, this guy’s a natural at it and I’m going to utilize that ability of his to help us with our team. So, I think J.J. was one of the first really, point forwards.”

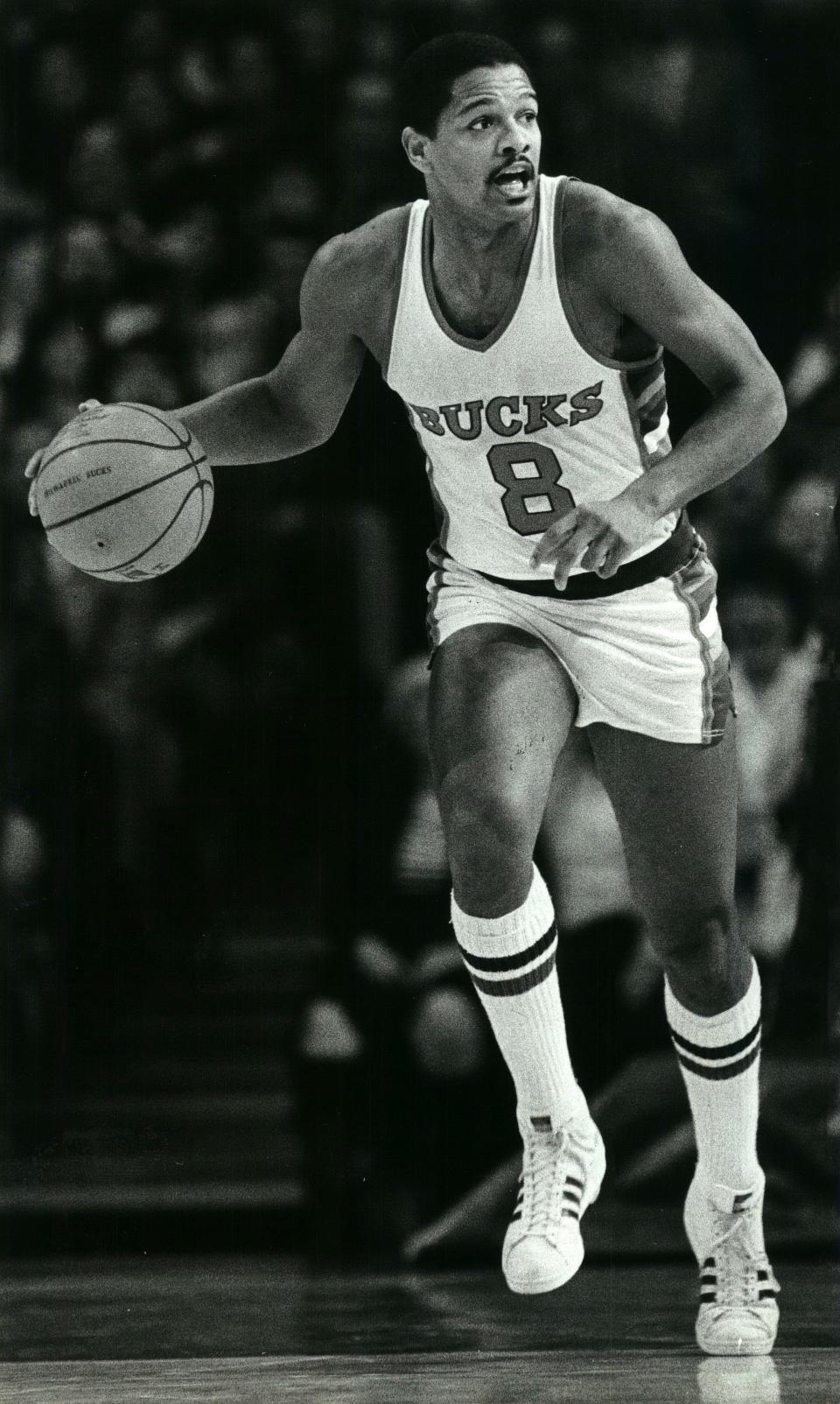

In Milwaukee, Marques Johnson relieved pressure

After a Madison native and a Milwaukee prep star ushered in a new dawn in basketball, the light reached the Bucks in the spring of 1984 – and Marques Johnson remembers it clear as day.

During a practice between Games 2 and 3 of the 1984 playoffs against New Jersey, Don Nelson devised a way to relieve the pressure Nets guards were putting on Dunleavy, then a member of the Bucks, as the team’s primary ball handler.

Nelson, cigarette and coffee in hand, decided putting the ball in the hands of the 6-7 Johnson would loosen up the Nets defense.

“They weren’t pressuring me at all,” Johnson recalled. “So ‘Nellie’ told me, ‘M,’ I want you bring the ball up the floor and get us into our offense.”

The coach walked his all-star through a handful of plays and it helped turn the series. The Milwaukee Journal wrote Johnson “handled the ball and was the offensive playmaker” following the Bucks’ series-clinching victory.

“If you had the ability to rebound, and you eliminated the outlet pass, you could take the ball yourself and quickly make plays just like a point guard would,” Nelson said. “Go ahead and dribble it up yourself, get in the middle of the court, and be aggressive and make plays in the open court. Marques was good at that.”

Who coined the name point forward?

What’s in a name?

Sometimes, it’s everything. Especially when you’re about to break long-standing positional boundaries. So, who came up with the sobriquet?

That remains clear for Marques Johnson, too.

“I said to him instead of a point guard I’m like a point forward,” he recalled of that practice in New Jersey. “’Nellie’s like, yeah, yeah, point forward, I like that you’re my point forward, yeah, I like that ‘M,’ point forward. It wasn’t like some big epiphany. It was a throwaway. It was at practice. Other guys were around, not sure if anybody heard it, nobody probably remembers it, it was a throwaway comment. That was the first time that term was ever uttered.”

Nelson and Harris, who by this time was an assistant coach in Milwaukee, first used the phrase together in training camp meetings at the Playboy Club in Lake Geneva in the late summer of 1984. By then, Johnson had been traded to the Los Angeles Clippers and the Bucks still lacked a true point guard.

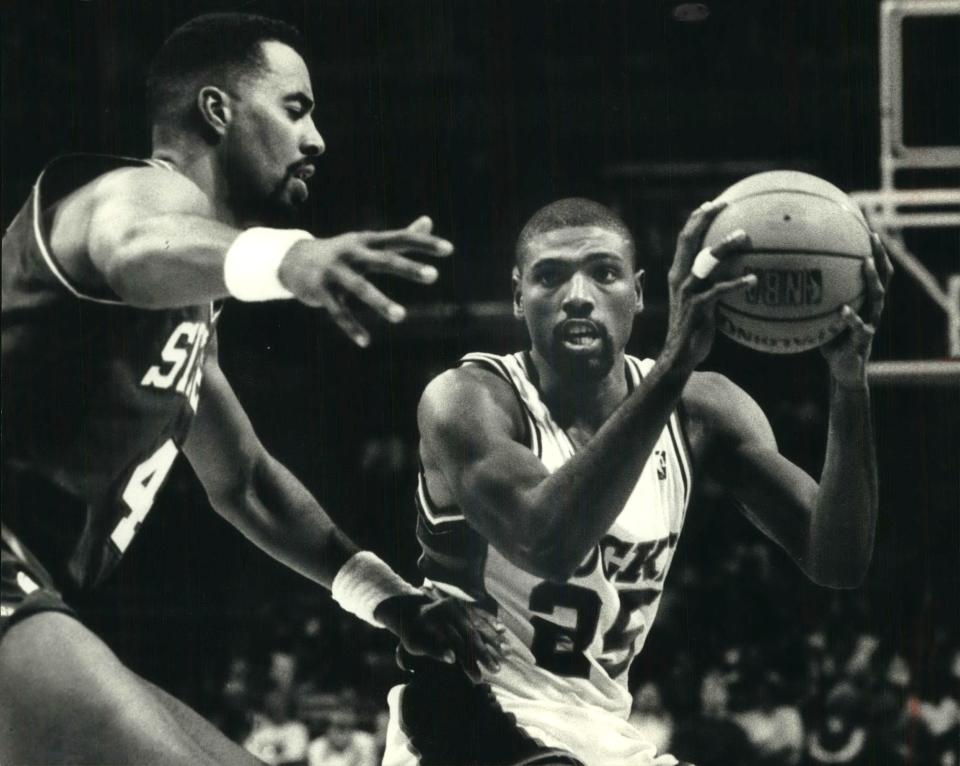

Their attention turned to Paul Pressey, a 6-5 forward entering his third season.

Harris reminded Nelson of how he and Nissalke used their forwards in Houston, and in a 2010 NBA.com story Harris said he dubbed Reid a point forward in meetings.

Reid confirmed this to the Journal Sentinel but, for their part, neither Nelson nor Harris was inclined to dispute Johnson’s memory.

“I guess somebody gave it a name, point forward. Maybe I did. I don’t even know,” Nelson said. “I don’t really talk about it that much. I can’t really remember if I started it or somebody else. It didn’t really matter. Plagiarizing is legal in sports. You can copy anybody you want and get away with it. Maybe I got the idea from somebody else. I don’t think I did, but if I did that’s all legal.”

He laughed.

What is not in doubt is Nelson was the first to say it publicly.

In Houston, Reid couldn’t help but notice there was growing attention on this new position he was intimately familiar with.

“(Nelson) did bring it to that next level because, let’s be honest, Milwaukee had a winning reputation,” he said. “And it was more noticeable. You had the No. 1 college player of the year, Marques Johnson, there. Now you’re getting all the notoriety. Robert Reid, NAIA from St. Mary’s? You just do it and you play and you don’t think about it.”

John Johnson, who passed away in 2016, has since been recognized as an early point forward.

“I don’t know if he ever used the same term,” his son Mitch Johnson said. “When we talked basketball, he would talk about himself like he was the point forward. And if he did, he definitely never said, oh, I made that up, like I created it, or all of a sudden someone called me that.”

Nissalke, Harris and Wilkens outlined the concept. Barry, Reid, John Johnson and Marques Johnson were the first examples of it. But it was Nelson and Pressey who stamped a new age.

“I was very fortunate and blessed to be in that position at that time that he gave me that title to run a point forward,” Pressey acknowledged. “That’s not taking anything from anybody.”

Paul Pressey was the first full-time point forward

Pressey played this new position full time in 1984-85 and averaged 6.8 assists, good for 17th in the NBA. He was the only player considered a forward in the top 40 in that category.

“He could handle, he could pass really well,” Nelson said. “He could envision plays and where the scoring opportunities would be and stuff like that. He had the mentality to be a point guard, really, so it made it a pretty easy decision.”

Though the 6-5 Pressey was bigger than other point guards, Nelson used him with smaller lineups including Sidney Moncrief (6-5), Dunleavy Sr. (6-3) and Craig Hodges (6-2) with 6-9 Terry Cummings playing the five position.

"Other small forwards had the mindset to shoot, or score first and pass later," Pressey said of his opponents. "I was a playmaker.

"You’ve got to learn to balance that (and) I'll take my shots when they’re there, but my first job was to get guys into the offense and get ‘em shots."

For Nelson and his players, it only made sense to use Pressey the way he did. But that sensibility began to splinter the rigid frames around NBA positions.

“They would put two guys on one side of the floor and play three against three, and then the small forward would play point forward,” said ESPN analyst Hubie Brown, who began his head coaching career against Nelson's Bucks.

“That changed the defensive rules and then that changed how you were going to play. That caused a lot of confusion within coaching early on of what were you gonna do?”

Pushing the point forward, forward

“I basically did it because I thought it was a good idea,” Nelson said of the point forward. “It took on a life of its own.”

And it evolved quickly.

Pressey, who averaged 7.1 assists from 1984-89, defined the position thusly: “When you take the ball out of bounds and give it to the small forward and he’s bringing the ball up the floor, he’s actually running your offense on a steady basis … at least 25 plays for you.”

While Pressey was mainly a facilitator, the 1990s saw Chicago’s Scottie Pippen (6-8) and Detroit’s Grant Hill (6-8) add a bigger, more athletic scoring element to the position.

Then came LeBron James, who was 6-7 as a rookie in 2003.

In his first decade, James averaged 27.6 points and 6.9 assists, including two seasons averaging at least 30 points and six seasons averaging at least seven assists. James would grow to 6-9, and running an offense at that size was no longer novel.

“’Nellie,’ to me, is the godfather of all that,” said Sacramento head coach Mike Brown, who coached James in Cleveland from 2004-15. “Because wherever he went, he tried to emulate that with a certain guy. He put non-traditional ball handlers, in my opinion, in that spot. It was a little easier for me to do that with LeBron.”

In the summer of 2013, the Bucks thought they might add a new chapter to the point forward story when they drafted a 6-9, 18-year-old from Greece.

"He’ll be able to play two, three, (the) one, point forward – that’s what he plays,” then-Bucks head coach Larry Drew said at Giannis Antetokounmpo’s introductory news conference on June 28, 2013. “That’s what comes to your mind when you watch him play because he has the ability to take the ball off the glass and he can take it coast-to-coast. And he makes plays. That’s very, very, very intriguing. It’s just not a lot of guys that can do that."

The gangly teen profiled a lot like Pippen for the Bucks' front office, but he had bigger goals. Literally.

"I’ll be like Magic, you know?" Antetokounmpo said that summer day with a wide smile. "Like (Kevin Durant) – mix ‘KD’ and Magic Johnson.

“I think it’s better that I grow because I’m a point guard. Six-10, maybe point forward as the coach says, and I think it’s better. I can play the point guard position. I can handle the ball very well. But the thing that makes me special in the game is I’m an unselfish point guard. I pass the ball to my teammates. And when the team needs a scorer, I’m that scorer."

Little did anyone know how he would not only grow into – but beyond – that role and help push it to near-extinction.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Players, coaches from Wisconsin key to point forward position in NBA