Go for 2 down 1? Inside the NFL’s most fascinating decision

On a raucous September Sunday in 2016, with an Oakland Raiders pullover not quite fully zipped, and a headset not quite fully blocking out New Orleans noise, Jack Del Rio made the NFL’s most intriguing decision before it had even presented itself.

It was the fourth quarter. His Raiders were about to receive the ball, down seven to Drew Brees’ Saints. “It was our season opener,” Del Rio recalls. “I wanted to convey confidence and belief to our team.” So he told quarterback Derek Carr – “BEFORE the drive,” he clarifies via text – “that we would not only score but then get the two-point conversion and win.”

History disagreed with him. Math disagreed as well. ESPN later explained that an extra point would have given the Raiders a 51 percent chance at victory. A two-point attempt slashed their win probability to 44.

Yet when Seth Roberts spun into the end zone, Del Rio raised two fingers. Carr connected with Michael Crabtree to give Oakland a galvanizing win. And Del Rio – now an ESPN NFL analyst – was feeling himself postgame.

“Good thing ESPN isn’t coaching the Raiders,” he quipped.

In a way, Del Rio’s all-or-nothing gamble was emblematic of a broader trend. In recent years, NFL coaches have strayed from their traditional conservatism. They are leaving offenses on fields on fourth down, or for two-point conversions, at soaring rates.

But going on fourth, going for two – these are trends supported by analytics. Del Rio’s? While he says his bold call was “a combination of the analytical and the gut feel,” the numbers didn’t support it. Nor did they support the Jacksonville Jaguars going for two down one this past Sunday in Houston, nor the Denver Broncos in a similar spot against Chicago.

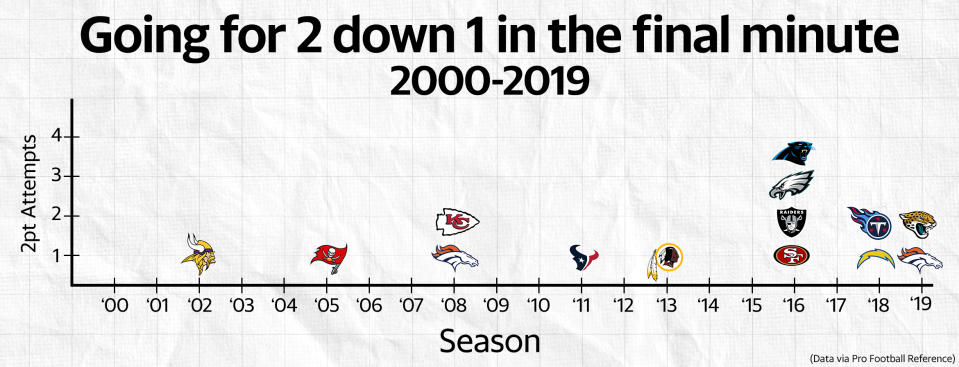

Fifteen times since the start of the 2016 season, NFL teams trailing by seven have scored touchdowns in a game’s final minute. Eight of those 15 have then gone for two. In other words, more coaches have taken Del Rio’s risk over the past three-plus seasons than in the previous 22.

The question is why. This trend, more often than not, runs counter to analytics. The math behind it is highly influential, but largely underexplored.

Which is why this decision – down one, final minute, go for two? – might just be football’s most fascinating.

Gut vs. Analytics

The NFL’s first successful all-or-nothing two-point conversion was the product of a coach’s gut instinct.

It was Dec. 15, 2002, and Mike Tice’s Minnesota Vikings trailed New Orleans by seven points late in the fourth quarter. Before his team launched a game-saving 13-play, 74-yard drive, Tice informed his offensive coordinator that he had no interest in settling for overtime if the Vikings scored a touchdown to pull within one.

“When we score, we’re going for two,” Tice boldly proclaimed.

At a time when risk-averse NFL coaches stubbornly clung to the notion that the safe option was always the best one, Tice believed he had good reason to defy conventional wisdom. He figured his overmatched 10-loss team had a better chance to get two yards on a single play than to outduel the playoff-bound Saints in OT.

So he called on Daunte Culpepper. Culpepper fumbled the snap. Tice's heart leapt into his throat. But Culpepper recovered and plunged in for two. The gamble paid off.

“We had lost so many close games,” Tice says now. “We felt like we might as well go for the win.”

[Watch live NFL games all season long for free on the Yahoo Sports app]

Seventeen years later, decision-making processes have progressed and diversified. Some teams nurture mathematical models to aid them. Take the Kansas City Chiefs, for example. When asked about the situation, head coach Andy Reid says: “You put everything in a hopper, and put it with analytics, also.” His trusted statistical analysis coordinator, Mike Frazier, “does all of that for us. … He's got a million charts up there. Anytime something new comes out, we jump on it.”

Yet the go-for-two-down-one decision is still largely a situational one made on instinct. Multiple coaches who spoke on the subject used some version of the phrase “every game is different.”

“You definitely talk about scenarios [beforehand], but there’s so many variables that go into the flow of the game,” Bears head coach Matt Nagy says. “The weather, how you’re playing. Are you playing catchup? Is it a high-scoring game?”

Adds Tice: “Are you home? Are you on the road? Do you have injuries that are going to hurt you if you go to overtime? Is your defense able to make another stop?”

And Tennessee coach Mike Vrabel, speaking last season: “Who's on the other side throwing the football?”

In his case, in Week 7 of 2018, it was Phillip Rivers. Vrabel’s Titans chose to go for two and the win, only to be stopped and sent home in defeat.

Coaches, in essence, are considering the relevant variables. What they lack is a proven method for weighing them. Instead of crunching numbers, they’ve taken a more simplistic approach. Of the 15 teams who've found themselves in this situation since 2016, all six favorites have kicked and bet on themselves in OT. All but one of the nine underdogs have gone for two.

Relative team strength aside, the prevailing thought seems to be that the decision amounts to a “50-50 proposition,” as Denver coach Vic Fangio recently called it. So when Fangio’s Broncos scored with 31 seconds remaining on Sunday to pull within one of the Bears, there were no nuanced conversations with statisticians. The choice, Fangio said Monday, was his.

“To me, the biggest part is just in your gut,” he said. “Analytics is good. Stats are good. But you just gotta go with your gut sometimes. And my gut told me to go for two there. Doesn’t mean I’ll do it the next time.”

“Overtime,” Vrabel said last year, “is a coin flip. You have the ball on the 2-yard line. Those are 50-50. It's a bunch of coin flips.”

Or is it?

Math enters the picture

The most qualified person to assess that question might be a former backgammon world champion with a passion for game theory.

Frank Frigo has long theorized that risk-averse football coaches were negatively affecting their teams’ chances of winning – especially with their reticence to go for fourth-and-shorts, two-point conversions and onside kicks. Over a decade ago, he began working to confirm his hypothesis and fill a market void by creating a simulation model to assess how win-probability changes in all kinds of customizable scenarios.

“It turned out coaches were making even worse decisions than we actually realized,” Frigo says.

In 2013, he co-founded EdjSports, a Louisville-based data-analysis firm that works with NFL and college coaches to help them improve their in-game risk management. EdjSports prepares custom reports for teams before every game to help them make optimal choices in every down, distance, field-position and clock situation.

Asked whether NFL teams should go for two or kick if they score a late touchdown to pull within one, Frigo says it’s a marginal decision that can lean in either direction depending on a number of factors. Chief among them: Extra-point and two-point conversion percentage, hypothetical overtime odds and – the variable most often overlooked by NFL coaches – time remaining.

The more time left for an opposing team to mount a last-gasp drive, the more likely Frigo is to recommend playing for overtime. That’s precisely what the Jaguars should have done in Houston on Sunday, per Frigo’s model, because the Texans had a roughly 30 percent chance to score on their final possession had Jacksonville converted its two-point attempt with a half-minute remaining.

Why so high? Because while teams in a tie game must tread carefully, those facing a deficit have increased incentive to take risks. Downfield throws and fourth-down aggression give them a disproportionately good chance to score on final-minute drives. Hours after the Jags failed to convert their two-point attempt this past Sunday, another tight contest provided Example 1A.

The Broncos converted their two-pointer to edge in front of the Bears by 1. But they left 31 seconds on the clock. With Chicago playing from behind, they were 31 desperate seconds. On fourth-and-15 – a down on which the Bears would have punted in a tie game – Mitch Trubisky found Allen Robinson for 25 yards. On the very next play, Eddy Piñeiro drilled a 53-yard game-winner as time expired.

Denver’s two-point proposition was unique. A penalty had moved the ball from the 2-yard line to the 1. “We thought that the Broncos needed to convert two-point conversions 53 percent of the time for it to be a good decision,” Frigo says. “From the 1-yard line, that’s far more justifiable.”

That the Broncos converted their two-point conversion and still lost, however, highlights the most overlooked peril of going for two.

If time is undervalued by coaches – Tice, Del Rio, Fangio, Chargers coach Anthony Lynn and others have boasted about predetermining decisions before drives – Frigo believes intangibles such as fatigue and momentum are overvalued.

Analytics demonstrate that underdogs, in fact, do have more reason to try to win a game on one play rather than over the course of a 10-minute overtime period. But Frigo says the chasm between two NFL teams must be vast for it to be significant. Had Jacksonville and Houston gone to overtime, their win probabilities were pretty even despite the Texans entering as 7.5-point favorites. By contrast, the undermanned New York Jets would have a significantly better chance to convert a two-point conversion to clinch victory than to try to win in overtime if they somehow get to that position as 23-point underdogs at New England on Sunday.

“That has to get some consideration,” Frigo says. “If you’re a huge dog in the game, you’re probably a bit of a dog in overtime. Why not take advantage of a highly leveraged situation to try to put the game away in one play?”

College at the forefront

A level below the NFL, college coaches have been doing this for decades. Championships have been won, undefeated seasons lost and legacies forever altered based on the choice between one and two. There was SMU coach Bobby Collins, perhaps costing his team a national title by settling for an extra point against Arkansas in 1982. And Tom Osborne, definitely costing Nebraska one two years later by going for the win and failing against Miami.

But the most famous Go-For-Two-Down-One decision punctuated one of college football’s historic upsets. In the 2007 Fiesta Bowl, Boise State pulled off a clever trick play to clinch a 43-42 victory over heavily-favored Oklahoma.

Sensing that his defense was tiring after Oklahoma rallied from an 18-point third-quarter deficit and then scored a touchdown on the first play in overtime, Boise State coach Chris Petersen elected to leave his offense on the field after the Broncos pulled within one with a score of their own. Petersen instructed three of his receivers to line up in a bunch formation as though Boise State was going to run one of its trademark bubble screens.

Quarterback Jared Zabransky looked that way to further draw the defense’s attention. Then, with his best Statue of Liberty impression, he handed the ball behind his back to tailback Ian Johnson, who ran untouched into the end zone.

Game that changed it all..

An Adrian Peterson lead Oklahoma vs. Boise St. Who remembers the chaos?

2007 Fiesta Bowl pic.twitter.com/HbIkG88j5u— MyBookie CFB (@MyBookieCFB) March 7, 2019

“It takes a lot of guts to go for two in that situation, but we felt like we had a great play in our back pocket,” Zabransky told Yahoo Sports. “We had probably practiced it 50 times against the scout team and it worked flawlessly almost every time.”

The importance of having a go-to two-point play handy is the greatest lesson from the college ranks. Even if that means Googling "good two-point plays" and then borrowing one from Alabama, like SMU coach Sonny Dykes did to find his overtime game-winner against Navy last season.

“All our players and coaches knew what play we were going to run,” Dykes says. “That’s a big factor in your decision when you have something you’ve been working on.”

Going for two and the win was also an easy decision for former Maryland interim coach Matt Canada when his team won the toss after taking heavily favored Ohio State to overtime last season. Canada’s gamble would have resulted in an upset victory too had his quarterback’s two-point pass been more accurate.

“An unbiased observer would probably say Ohio State had better players spot for spot,” Canada says. “If you’re an underdog, you can end it on one play, and you have a play that you think will work, to me that’s when you go for two.”

So, is there a right answer?

It took more than two decades for Canada’s line of reasoning to become commonplace in the NFL. Over the first 16 seasons of the 21st century, 71 teams found themselves down one in the fourth quarter’s final minute, having just scored a touchdown, facing football’s most fascinating decision. A mere six pushed their chips all in.

Tice was one of them. But he was acutely aware of one reason his contemporaries chose not to.

“If we didn’t convert there,” the retired coach says of his groundbreaking two-point success in 2002, “I knew the media was going to rip my ass.”

In 2019, the discourse is far more civilized. Unconventional choices rooted in data are far more respected. Their gradual acceptance has helped unleash a wave of analytics-driven aggression, a wave which the eight coaches who have attempted final-minute two-pointers down one over the past three-plus years are surely riding. The ones who fail are still scrutinized, but not ridiculed. The ones who succeed are championed as pioneers.

But should they be? Should coaches in this specific situation be riding that wave?

"Generally, as a rule of thumb, we lean on the side of more aggression,” says Frigo, the statistical analyst. “But in this situation, it’s so situationally dependent."

In other words, it’s complicated. Coaches have been emboldened by numbers, but in this case not always endorsed by them. Which is why their decisions are so unique, each its own mysterious animal. They are marginal and murky, and most of all rare, all of which explains why, in the grand scheme of football coaching, they are relatively unexplored.

But when two is the call, they turn 60 minutes of finely choreographed brutality into the whimsical flip of a switch inside an observer’s head. They decide games, swing seasons, change futures. And the most interesting thing about them?

Precisely because they are so murky, precisely because their margins are so fine, still, in 2019, there is no definitive guide to making them.

– – – – – – –

Yahoo Sports’ Terez Paylor contributed reporting from Kansas City.

Jeff Eisenberg is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email him at jeisenb@verizonmedia.com or follow him on Twitter.

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.