A future NFL QB, an All-American RB and a relentless D. Story of IU's last bowl winners.

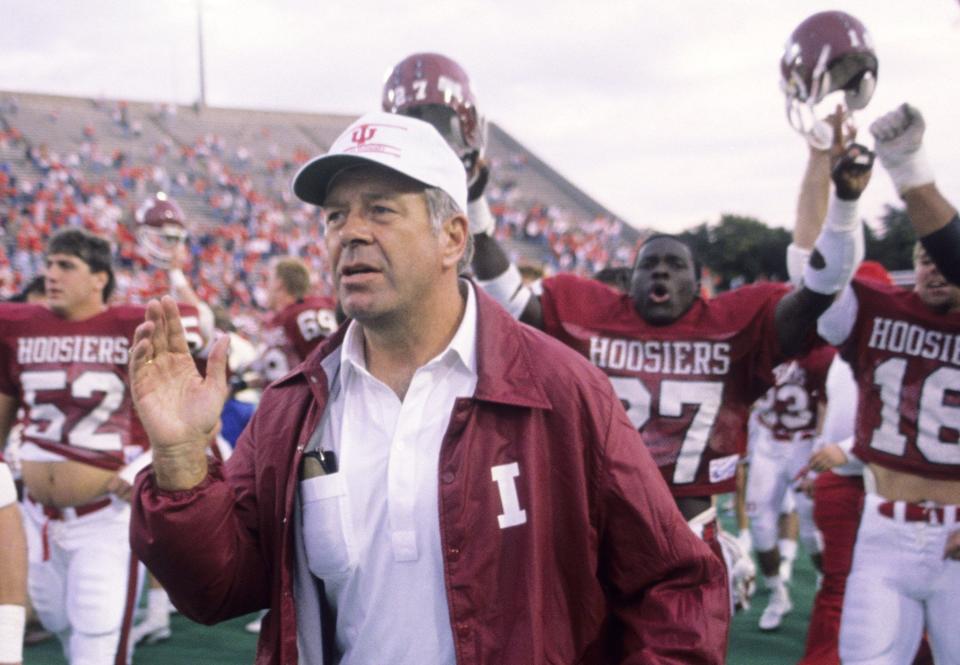

BLOOMINGTON – In the summer of 1991, then-Indiana coach Bill Mallory joined a junket of coaches brought together for an offseason trip sponsored by Nike.

When he got home, Mallory pulled longtime defensive coordinator Joe Novak aside, and told Novak the two of them were going to Miami. There, Jimmy Johnson was having success running a more flexible defense — specifically, it moved from a five-man front to four — and Mallory wanted to study it up close.

“They were running a 4-3 defense,” senior linebacker and captain Mark Hagen said. “We felt like we had the personnel to be effective with it.”

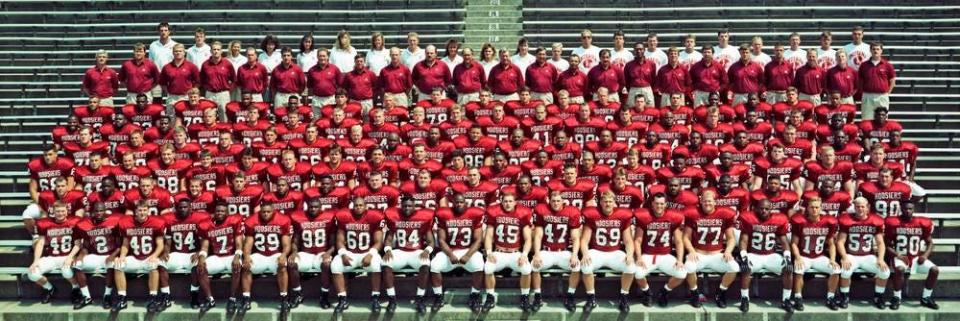

With some clear early season growing pains, Mallory’s decision still helped set the stage for one of the best seasons of his tenure, and IU’s most dominant bowl performance ever. With Trent Green behind center, Vaughn Dunbar steamrolling his way to All-America honors and that defense becoming one of the best in program history, the Hoosiers wound up winning the 1991 Copper Bowl — making them the last Indiana team to win a bowl game.

This is their story.

DOYEL: Cignetti flipping everything IU's way: recruits, narratives, hope

***

Indiana arrived to 1991 with a solid core of seniors, a star in Dunbar and a coming force at quarterback in Green.

Mallory’s switch to the 4-3 was well received. It mixed a talented linebacker group, led by Hagen, with a deep defensive line. With early trips to Notre Dame and Missouri on the schedule, the Hoosiers were anxious to get on the field and see where they stood.

Hagen: “I think any time you finish your college career, you want to finish strong. I think that’s what we were able to do. There was a strong group of seniors in that ’91 season, a lot of guys I’d played five years of football with.”

Already, Mallory had established himself as IU’s best-ever head coach. His players, who as alumni have taken to the term “Mallory Men,” handed down a culture of winning that eventually included six bowl berths in eight years, wins over Big Ten powerhouses like Michigan and Ohio State, and Anthony Thompson’s Heisman runner-up finish.

The players Mallory had recruited in his first 3-4 years on the job were coming of age now, as college juniors and seniors. They’d been with Mallory and his staff as they built teams that enjoyed virtually unprecedented success in the Big Ten and the postseason. This was their turn.

Greg Farrall, senior lineman/linebacker: “What we went through, all the way from Black Monday and the (1984) 0-11 team, all the way up to Trent and the guys from the next few years, we’re the men we are today because of him. … That man was like a second father to many of us.”

Up first in 1991 was a trip to South Bend. Lou Holtz’s team began the season ranked No. 7 nationally, with junior Rick Mirer behind center. Riding its remade defense, Indiana kept things competitive until Notre Dame turned loose a bruising sophomore running back from Detroit named Jerome Bettis.

Farrall: “We were doing great until they gave Bettis to us. It was like trying to tackle a redwood tree.”

Hagen: “They finished the game with a third-string Jerome Bettis out there. I think he went for about 100 yards in the fourth quarter.”

Indiana lost 49-27, but backstopped that defeat with a win over Kentucky and a tie at Missouri.

Then came Michigan State. The Spartans had been a thorn in Indiana’s side through the 1980s, often competing alongside the Hoosiers at or near the top of the Big Ten. A famous locker room moment still captured on YouTube following their 1987 game reflects Mallory’s fierce but respectful personality, the IU coach congratulating Michigan State in the Spartan Stadium home locker room after the win that essentially clinched the Spartans the Big Ten title.

Buck Suhr, running backs coach: “We prided ourselves on being physical, and they did too.”

Michigan State was known then for a demanding style of football, under George Perles. His teams had at times exerted that physicality on Indiana. This time, the Hoosiers were ready.

Despite it being early October, snow fell as the two teams warmed up. One eventually had to stop, but not for the weather — Indiana’s players were hitting so hard in warmups, coaches pulled them off the field.

Suhr: “We had to call that one off, because we were going after each other so hard that day that we just blew the whistle and said we can’t do this anymore. Somebody’s going to get hurt.”

There had been some competitive games in the Old Brass Spittoon series under Mallory. The 1991 meeting was not one of them. Despite riding Tico Duckett, the Big Ten’s offensive player of the year the previous season, Michigan State managed just 33 rushing yards. A full box score is hard to come by, but at least one retelling for this story suggested the Spartans never even crossed midfield.

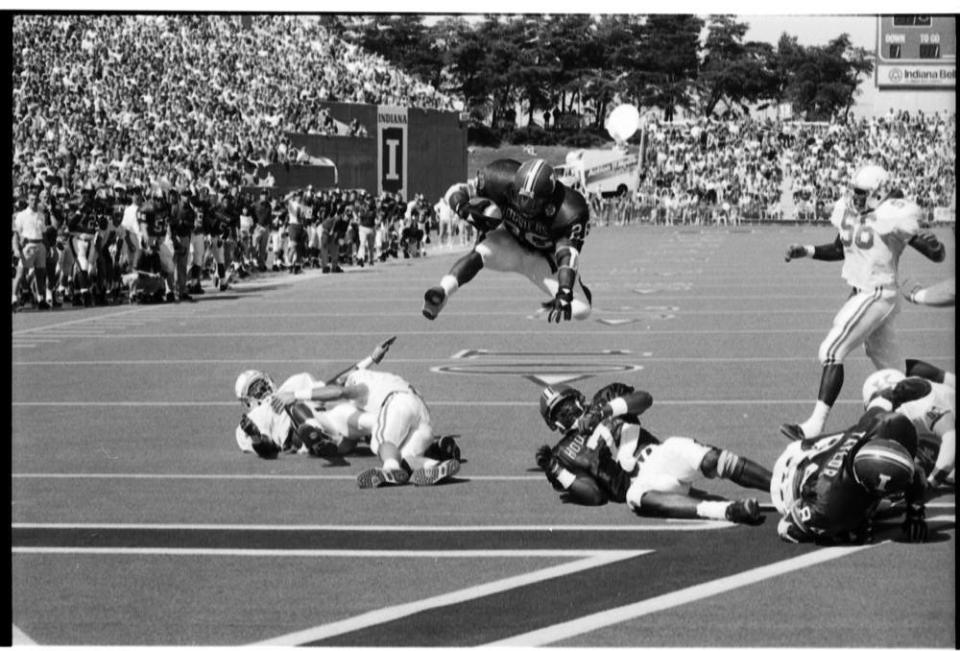

Green passed for 241 yards, while wide receiver Eddie Thomas accounted for 101 of those. Dunbar finished with 158 total yards on 29 touches. Indiana won, 31-0.

Victory exorcised a few demons, but also offered a glimpse of what the Hoosiers could be — both on defense, and on offense.

Hagen: “We shut out Michigan State. That’s when you kind of saw the defense ignite and play with a lot of confidence.”

Trent Green, quarterback: “That was a really big moment.”

***

The Michigan State win sparked a run of four victories in five games, a stretch that set the Hoosiers on their way. Yet it might be the one loss in that run, 24-16 at Michigan, that’s remembered best.

Led by Elvis Grbac, Ricky Powers and eventual Heisman Trophy winner Desmond Howard, the Wolverines finished that Big Ten season a perfect 8-0, before losing the Rose Bowl to Mark Brunell’s Washington. They steamrolled their way through the conference, beating Iowa by 21, ranked Illinois by 20 and rival Ohio State by 28.

Their toughest game in Big Ten play: an Oct. 19 lunchtime kickoff against Indiana.

Suhr: “We had some really close calls. Michigan was a game where we got pretty much screwed.”

Indiana lost by eight, Michigan’s game-sealing touchdown coming on a late pass from Grbac to Howard.

Farrall: “He throws this ball on the end zone on a post route to Desmond, he lays out parallel to the ground, perfect fingertip catch in the end zone. I remember saying to myself, ‘Jeez, if you’re gonna lose, I guess lose like that.’”

Mallory’s frustration, however, lay in what came before. On an afternoon when Indiana coaches saw the whistle blow against them over and over, things boiled over when that Michigan touchdown drive was extended because of a defensive holding penalty.

History remembers it differently based on who tells it. Some former Hoosiers swear the call itself was weak. Others suggest officials first whistled pass interference, and upon realizing the ball was uncatchable, changed their call to holding.

Suhr: “They threw a fade into the end zone. The ball landed in a tuba. The flag comes out and they call interference. It’s obviously an uncatchable ball. It landed in the tuba section. They get together and call holding. You can’t do that.”

The play stood, and the score eventually did too. At his weekly Monday news conference two days later, Mallory openly criticized the way the game had been officiated.

Mallory, from the Chicago Tribune, Oct. 25, 1991: “The officiating was not acceptable. I’m not going to sit here and be muzzled by this thing. You can stick it. Our players work too hard and our coaches work too hard for (the officials) to go in and slop around in a game like that.”

“This thing” was a beefed-up Big Ten policy against public criticism of game officials, pushed for by then-Commissioner Jim Delany the summer before. Mallory, among the most widely respected coaches in the conference, was an unlikely candidate to be first to run afoul of that rule, but Delany punished him nonetheless, suspending Indiana’s coach for the next week’s game at Wisconsin.

Still, the Michigan game had proven some of Indiana’s offseason adjustments worthwhile. That 4-3 defense stood up to Michigan as well as any in the Big Ten that fall. And adjustments to a Green-marshaled passing attack — including more checks at the line for Green and the introduction of hot routes — advanced IU’s offense as well.

Green: “(The offense) evolved a lot. Even though that season we ended up losing the controversial game up at Michigan where coach Mallory got suspended, we had a lot of success against Michigan with that offense.

“That was something new to us, and new to the Indiana program. Give a lot of credit to the coaches for adapting and changing to that, the players for accepting all that change, and that was an explosive offense in that era.”

Michigan remembered the encounter, a close win in a famous season. Indiana left aggrieved. But there’s a footnote to the history of that game lost in time, one Suhr hasn’t forgotten 22 years later: That crew was flagged for 14 missed calls, and suspended for the next week itself.

Suhr: “To give Michigan credit, Desmond Howard was awesome against us that day.”

The Hoosiers followed that loss with a trip to Madison. Without Mallory, and against a Wisconsin team coached by Barry Alvarez and captained by Troy Vincent, IU struggled badly in the first half, trailing 17-0 at the break.

Mallory could only go as far with Indiana as the team bus to head to the stadium, because of his suspension. In his absence, coordinators George Belu and Joe Novak tried to rally a team that eventually fell behind 20-0.

The rally came. Dunbar played through a pinched nerve in his shoulder, and Indiana’s defense only allowed five second-half first downs. Green ran for two touchdowns in the fourth quarter, icing a 28-20 win.

Suhr: “Vaughn Dunbar put us on his back and pounded them with a terrible shoulder. That was another one of the stories that made that team really special.

“We won that game for coach Mallory.”

***

Road losses to Iowa and Ohio State set up an Old Oaken Bucket tilt with Purdue that might have had bowl eligibility riding on it.

The Hoosiers were at that point 5-4-1, their tie at Missouri keeping them from the coveted six-win threshold. Bucket games around that time often carried significant stakes, for both sides. But this time, Purdue was at the finish line of an eventual 4-7 season in Jim Colletto’s first year as coach. The goal was to keep IU from bowling.

Indiana tore off a 24-6 halftime lead, before Purdue scored 16 unanswered to set up a potential game-winning 35-yard field goal. Joe O’Leary, who’d already missed three kicks that day, pushed his final effort well wide of the post. Indiana, 6-4-1, confirmed its postseason.

Hagen: “There were certainly a lot fewer bowls back then, so nobody was gonna take a team that didn’t have six wins.”

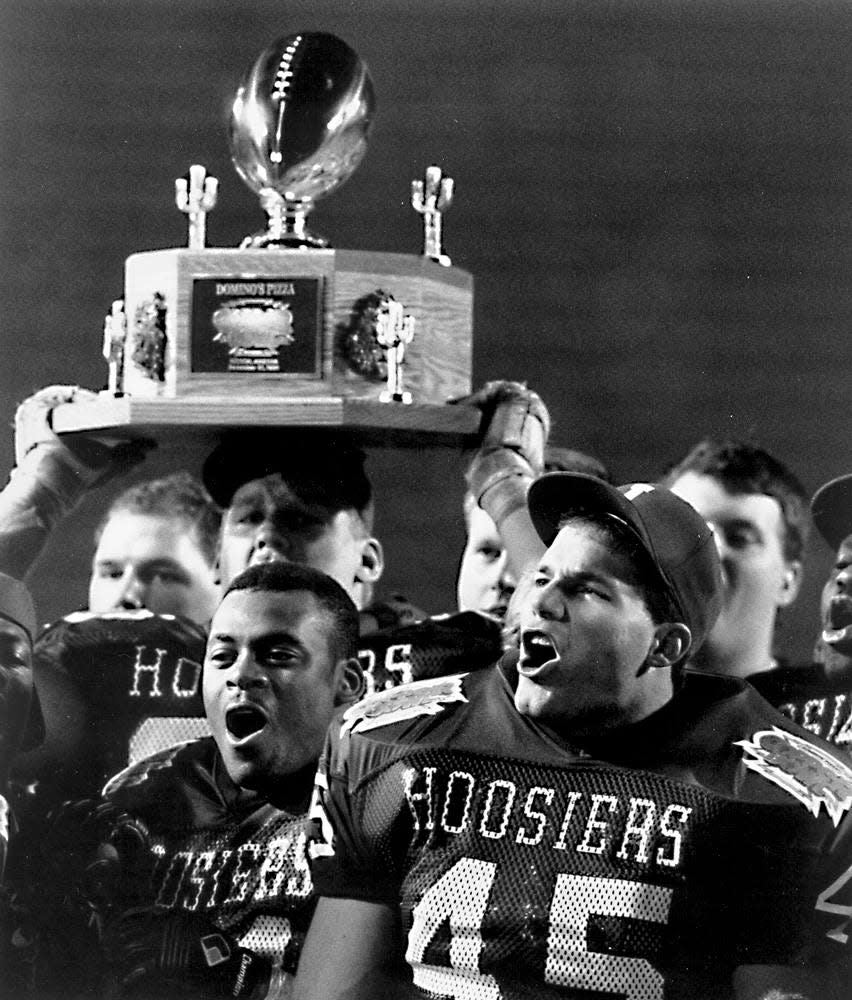

Next stop: the Copper Bowl, in Tucson, Ariz. The Hoosiers drew Baylor, runners up in the old Southwest Conference.

The Bears finished the regular season 8-3, behind quarterback J.J. Joe and defensive tackle Santana Dotson. They counted wins at Colorado, at Arkansas and at Texas on their ledger. They headed to the desert as favorites, and they acted like it.

Rod Carey, offensive lineman: “We definitely felt the arrogance from Baylor. Everyone was just a little put off by that.”

It was Mallory’s fifth bowl as IU coach. He and his staff, to the surprise of their roster, decided to change their schedule in the week leading up to the game. Everyone took to the tweaks quickly. The week that followed exceeded anyone’s expectations.

Carey: “We went to, that year, morning practices at the bowl site. We were an afternoon practice team. Everyone was a little like, huh? But after we got into the morning routine, everybody liked it, because they had their afternoons free, they had their evenings free.

“Everyone was excited to get to practice and get it over, instead of waiting all day at a bowl site for an afternoon practice.”

Suhr: “It was a really good week. We stayed in a good place and had good practices. There were no bad events.

“Bill was pretty intense that week. We stayed at it.”

All the while, IU attended bowl events with their opponent, absorbing more of Baylor’s perceived arrogance. They heard suggestions from attending media the Bears were a heavy favorite, that it would be a surprise if Indiana even kept things close.

Green: “We got down to Tucson. They had several team events with both Baylor and Indiana present, and it was very noticeable early on and throughout the course of the thing that it was Baylor’s bowl game and we just happened to be their opponent. Not that they said anything, it was just the vibe of the whole thing.

“Going into that bowl game, we all felt like we were better than our record and we wanted to prove it on that stage.”

Hagen: “Not one thing seemed to be said about our defense, so that kind of pissed us off a little bit. We really felt like we had something to prove, going out and shutting them out that night.”

Carey: “We kept hitting them in the mouth, and they started chirping louder and louder, and then pretty soon, they stopped chirping, because we didn’t stop hitting them in the mouth.”

Farrall: “To hang it up, have our last game to play against Santana Dotson, in the Copper Bowl, we were not favored — I don’t believe we were — and we smoked them. We beat their ass.”

The game, played on New Year’s Eve 1991, was never very close.

Baylor managed to stay relatively competitive in first downs, and total yardage, but Indiana led in both categories. The Bears fumbled the ball four times, losing one, and committed two turnovers to IU’s none. The Hoosiers led 17-0 at halftime, and finished with one last touchdown in the fourth quarter. Green ran for two, Dunbar one. The favored Bears never scored.

Indiana won, 24-0.

Green: “I just remember getting back to the hotel and of course all the alumni, the coaches, the families, everybody’s greeting us back at the hotel.

“It was just a big festive sendoff for the seniors, and ringing in the new year.”

Hagen: “For me personally, it was a great way to go out, finish my football career.”

Suhr: “It was one of our better bowl trips not just because of the win but the way we prepared and everything.”

Carey: “That was really satisfying.”

Dunbar was a consensus All-American in 1991. Green would be drafted into the NFL two years later. A handful of other players from that team would eventually turn pro, or be elected into Indiana’s athletics hall of fame, or both.

For players like Hagen and Farrall, it was a satisfying end to a career spent building onto success in a program that had too rarely known it. It would prove Mallory’s final postseason win at Indiana.

It is, to date, the Hoosiers’ last bowl victory, a distinction that team’s alumni wear with pride, but one they are also ready to pass on.

Farrall: “None of us want to own the record of winning the last bowl game at Indiana University in 32 years.

“We’re ready for some wins.”

Follow IndyStar reporter Zach Osterman on Twitter: @ZachOsterman.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Indiana football bowl history: Hoosiers' last win is 1991 Copper Bowl