The city that hated its NFL team

It seems a simple enough recipe: combine a football-mad population with a team needing a home, and bang, instant love affair. And it almost always works — see Baltimore, Phoenix, Indianapolis and Charlotte, for instance. Even when the matchmaking doesn’t result in an immediate connection, the spark eventually flames up — see, say, Los Angeles and the Rams.

But only once in the NFL’s history have a team and a city actively hated each other right from the jump, only once has the relationship turned so ugly that the plug got pulled after just a few months. Like all bad relationships, it faltered on the rocks of jealousy and pain, and also like all bad relationships, both parties would just as soon forget it ever happened.

This is the story of a city that, for one brief season, was an NFL town … and hated every minute of it.

The NFL almost had the Memphis Hound Dogs

If fate’s wheels had turned in a slightly different direction, you’d be reading previews right now of how well the Memphis Hound Dogs will stack up in 2018 against their AFC South rivals. The “Heartbreak Hotel” would be as feared a section of fans as Cleveland’s Dawg Pound or Oakland’s Black Hole. The possibility was there, but the NFL chose a different path, one that led far away from Memphis.

For all its prestige as a musical hotbed, Memphis is, in truth, a very large small town. Hard up against the Mississippi River, far from any coast, weird in a way that can intimidate the comfort-minded, it’s all too often a place you stop through on the way to someplace else. If you’ve sent a FedEx package in the past 30 years, chances are it’s routed through Memphis.

“We’re not a city that has all the advantages of a coastal city, we’re not a city that has a dozen Fortune 500 companies,” says Frank Murtaugh, managing editor of Memphis magazine and a 30-year Memphis resident. “But we have desire, we have heart, we have devotion, the core components to being a long-term sports fan. We just needed a winner.”

Memphis’ uneasy relationship with the NFL dates back decades, as the city had tried time and again to pretty itself up to attract the league’s attention, and time and again watched as other cities snared or were awarded new teams.

The Memphis franchise of the World Football League, dubbed “the Grizzlies” three decades before the basketball team arrived, boasted notables like Danny White and Larry Csonka, and brought football madness to the Mid-South in the mid-’70s. When the league folded, the team collected season ticket deposits from 40,000 fans to try to entice the NFL to bring the Grizzlies into the fold; the NFL refused.

Ten years later, the Memphis Showboats of the USFL were one of the league’s highlights, selling out the Liberty Bowl for games like a June showdown against Birmingham. (Getting Memphians to do anything in the river-soaked heat of June is an astonishing achievement.) But when the USFL evaporated following a lawsuit against the NFL brought by one of the league’s owners, a New York businessman by the name of Donald Trump, the city once again found itself team-less.

In 1987, Memphis spent $19.5 million — about $43.2 million in today’s dollars — to refurbish the already-dated Liberty Bowl, expanding bench seating to 62,000 and adding 44 luxury suites to the saddle-shaped concrete oval. The city then sat back and waited for the NFL to call … and then watched in horror as Phoenix, like Indianapolis before it, vultured away an existing franchise.

Six years later, Memphis took another shot at the league, with an ownership group that included local big shots like Fred Smith, founder of FedEx, and Elvis Presley Enterprises. Memphis pitched a team — “the Hound Dogs,” a byproduct of the Presley estate’s connection — to the NFL, facing off against four other hopefuls: Charlotte, Jacksonville, Baltimore, and St. Louis. (Bar trivia: while Jacksonville had already settled on the “Jaguars” name, Carolina initially called its prospective team “the Cougars,” while Baltimore offered “Bombers” and St. Louis, “Stallions.” The 1990s were not a great era for potential team names.)

Based on that list, you can guess what happened next. All four of those other cities got franchises – Charlotte and Jacksonville won the expansion bids, and Baltimore and St. Louis lured teams from other cities by building far splashier stadiums than the Liberty Bowl. Memphis couldn’t win on its own merits, and it didn’t have the goods to pull another team away from its home.

So Memphis sat back, licked its wounds – it was used to that by now – and tried to find comfort in college basketball, where a kid named Penny Hardaway had brought some national prominence back to the local university program.

Houston and the Oilers: an ugly NFL breakup

About 600 miles away in Houston, a football-mad city was growing ever more angry with its team … and more specifically, with its owner, Bud Adams. Adams, who made his fortunes in oil, was the anti-Memphis, a gambler who’d beaten the NFL every time he turned over his cards. A charter member of the old AFL, he signed 1960 Heisman Trophy winner Billy Cannon right out from under the NFL’s nose, then won a court battle to keep him. Nearly 20 years later, he won the rights to the prized Earl Campbell in an all-in trade with Tampa Bay, and rode Campbell right to the top of the AFC. But Adams seemed cursed to never see the promised land of the Super Bowl; the Steelers thumped Houston in two straight AFC championships, and a decade later, Houston suffered the worst collapse in playoff history, losing a 1993 AFC wild-card game to Buffalo after leading 35-3.

Like Memphis, Adams had watched with envy as the Rams moved into fancy new digs in St. Louis. But while Memphis coveted a team, Adams lusted after the stadium. The Astrodome, where the Oilers had once played to tens of thousands of raucous Luv Ya Blue fans, was a decrepit, echoing dump, and not long after that playoff collapse, Adams began demanding $186 million for a new stadium. Houston turned on him, hard, and a 2-14 season in 1994 didn’t help his case.

So Adams started casting a wayward eye around the country, looking for another home, and lo and behold, then-Nashville mayor Phil Bredesen rolled out the red carpet. He spearheaded a May 1996 referendum where Nashville residents, visions of Super Bowls dancing in their heads, voted to bear the brunt of funding for a proposed stadium via property tax increases. At the same time, NFL owners approved Adams’ move to the Volunteer State by a 23-6 margin, with one abstention – the bare minimum needed for the go-ahead.

Adams played cagey with Oilers fans, the media, and his own players – members of that last Houston Oilers team were getting their updates from the newspaper, if at all – and that led to the awkwardness of three consecutive lame-duck seasons. Houston played its final game in December 1996 before a crowd of barely 15,000.

“It was handled so poorly,” Hall of Fame offensive lineman Bruce Matthews said. “If anything – I think about the Rams and Chargers – we set an example in how you don’t want to move a franchise. It was a wreck.”

Plus, there was a problem at the other end of the pipeline. Nashville wouldn’t have its stadium ready until the 1998 season. That meant the Oilers would have to find a place to play for two years. Adams initially assumed the team could play in Vanderbilt’s 41,000-seat Dudley Field, but that had a few problems: first, there were none of the skyboxes for that sweet, sweet corporate revenue, and second, the stadium couldn’t sell alcohol, being an NCAA site. (The University of Tennessee’s Neyland Stadium had a tough-to-fill capacity of 102,000; Adams was spooked by the thought of large swaths of empty seats, which turned out to be more than a touch ironic.) Combined, both college stadiums were a no-go.

Adams then looked to another option that he assumed counted as “local” – the Liberty Bowl. It was a decision one makes by looking at a map, not by consulting anyone with any awareness whatsoever of either city. Memphis was just three hours down Interstate 40, the reasoning apparently ran; this was as close to a perfect solution as you could get … right?

Nope. Nashville and Memphis loathed each other, Memphis seeing Nashville as a pretentious, hopelessly conventional suburban enclave and Nashville seeing Memphis as a trying-too-hard, affected-cool backwater river town. The two cities have spent a century trash-talking each other for everything from music (country vs. blues) to food (hot chicken vs. barbecue) to on-brand nicknames (Smashville vs. Grind City). Assuming Memphis fans would support a Nashville team was as naïve as assuming, say, New York Giants fans would go to Jets games, or that Houston fans would babysit a Dallas team. A full 20 years before the Chargers’ brain trust assumed San Diego-based fans would make the drive to Los Angeles, Adams figured the three-hour drive between the cities would be no hurdle at all.

He figured wrong. When the NFL came calling one more time, expecting a warm reception, Memphis – burned so many times before – wasn’t biting.

Memphis to NFL: Drop dead

“They seem to think that all they have to do is hang out a sign at the stadium and watch Memphians and Nashvillians line up to buy tickets to see the Oilers play,” local writer Dennis Freeland wrote in the August 28, 1997 edition of the Memphis Flyer. “The Oilers have done almost nothing to ingratiate themselves to the fans of either the city where they live, practice, and hope someday to play, or the city where they are playing while Nashville completes a new $292 million stadium.”

Adams and the NFL showed about as much concern for Memphis as you’d show for a parking spot at a grocery store. He dubbed Memphis residents “Memphanites,” whatever that meant, and then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue doubled down by referring to then-Memphis mayor Jim Rout as “Mayor Stout.”

Clearly, this was a temporary layover, nothing more.

“Houston was done with us, and Memphis wasn’t thrilled,” then-Oilers general manager Floyd Reese says. “It all happened so fast. We didn’t have enough time to get things how we wanted.”

“It was billed to us as, once this all goes through, it’s going to be great,” Matthews says. “Instead it got weirder and stranger.”

Attempts to ingratiate the team with its babysitter failed miserably. The team attempted a meet-and-greet by bus from Nashville to Memphis, and stopped in Jackson where indifferent fans and befuddled players stared at each other in 98-degree heat. Later came a disastrous attempt at a team parade through Memphis’ Beale Street … a parade where nobody showed up.

“We were coming down on the red carpet to this open-air park,” Eddie George recalls. “The sides were all roped off. But there was no one there! Maybe 150 people showed up!” Several Titans just ducked under the rope line to go buy beers from street vendors.

“In the NFL, travel is a five-star affair. But the hotel we stayed in in Memphis was second-rate,” Reese says. “You’d take the plane to Memphis, you’d go into the same room you’d been in before, and the same light was blinking on the phone with the same message that had been there the last three weeks.”

“We were always on the road once the season started,” Matthews says. “It was just so ridiculous. We kept saying, ‘When are we getting to the real thing? Where’s the comfort zone? We were never feeling it.’ ”

The players would fly to Memphis on a Saturday night for a Sunday game, parking at that dismal hotel and just trying to figure out what to do next. They even had to take cabs from their hotel to the game itself.

“Memphis was not a big town,” George recalls. “It’s changed a lot, but back then, there was not a lot to do the night before the game. You’d show up, you’d play, you’d leave. Maybe we’d get some barbecue or go to a jazz or blues club to relax, but that was it. There was no chance to connect with the town.”

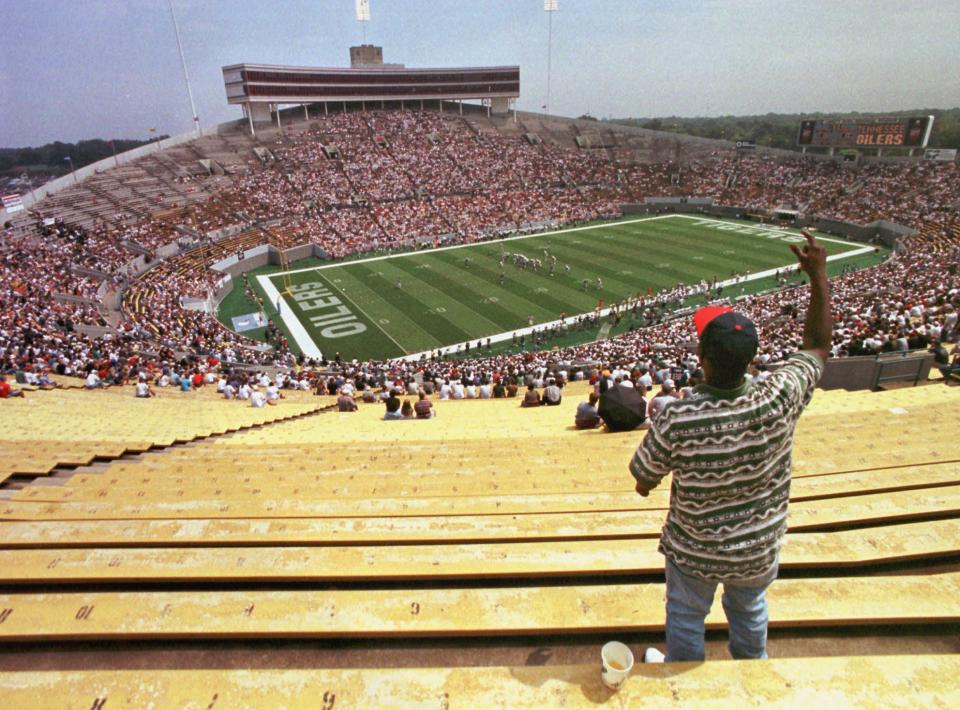

Visitors to Memphis included Oakland, which brought out a huge contingent of bandwagoning local fans, and Cincinnati, which … didn’t. The Bengals game drew a reported attendance of barely 17,000 mildly interested fans who couldn’t even muster up enough noise to be heard a block away from the Liberty Bowl.

“[Opposing teams would] come in and just be shaking their heads,” Reese says. “They understood. We were playing in a stadium that was not of NFL caliber. You’d apologize, but there was nothing you could do.”

“It wasn’t a destination. Your week wasn’t scheduled around the ball game,” Murtaugh recalls. “People went if they didn’t have anything better to do that day.”

Tickets cost $25 to $60 (about $40 to $95, in today’s dollars), but even at those reasonable rates, nobody showed up. The insult-to-injury schedule brought both Jacksonville and Baltimore to the Bluff City to remind Memphians of what they’d missed out on. Somehow, the team won six of its eight games in the Liberty Bowl. (The Jeff Fisher-coached team went 2-6 on the road to finish at a perfect 8-8.)

George, the team’s young centerpiece, suffered a whiplash culture shock; his first year as an Oiler was the team’s last in Houston. “He was fresh off the Heisman [at Ohio State] and playing in front of 102,000 people,” Reese said. “And here he was, playing in front of 20,000 people. I kept telling him and everyone else, ‘Guys, hang in there. It’s going to get better.’ ”

For the year, George rushed for 1,399 yards and six touchdowns. The Oilers’ mobile young third-year quarterback, Steve McNair, posted respectable numbers, and the rest of the team made a vow: this season wouldn’t break them.

“We didn’t know what to expect one week to the next,” George says. “But once we added some key pieces it made us invincible. We got over the hump, and having that [adversity] to bring us together helped.”

While the locker room bonded, the front office fractured. The season’s final game tipped Adams’ fury. The Steelers came to town, and attendance swelled to more than 50,000, by far the best mark of the season. But there was a reason for that: it was cheaper for Steelers fans to buy airfare, a hotel and a ticket to an Oilers game in Memphis than a hometown game at Three Rivers. Enraged at the sight of black and gold legions drowning out the few baby blue faithful, Adams pulled up stakes and hauled the team back to Nashville for good. No NFL team has played a regular-season game in Memphis since 1997, and nobody seems too upset about that.

Memphis and the Oilers: Better off after the breakup

The fortunes of Memphis and the Oilers turned upward after that disastrous season. Two years later, the Oilers – rebranded as the Titans – reached the Super Bowl and fell 1 yard short of a potential overtime. Players who’d suffered through the dark days in Houston and the desolate days in Memphis credited the adversity for bringing them together as a team, strengthening their bonds.

“No question,” Matthews says. “When you’re crappy for a while, you’re drafting high, and we were 8-8 for three years in a row. But it culminated in that ’99 team that went to the Super Bowl.”

“Over three different seasons, we were spread over three different cities, in three different stadiums, with three different names,” Reese says. “We didn’t get a chance to know who we were.”

Memphis took steps forward as a sports town, too, welcoming the Triple-A affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals to a brand-new downtown baseball stadium, a far cry from the rickety dump that sat in the shadow of the Liberty Bowl. Less than four years after that disastrous Oilers season, Memphis ended up on the winning end of a pro relocation, welcoming the NBA’s Vancouver Grizzlies to town. Sure, the town would still see a run of off-brand and untested pro football teams – the XFL’s “Maniax” called Memphis home for a year in 2001, and the new Alliance of American Football will have a team in Memphis – but thanks to the Grizzlies, Memphis is now a legitimate pro sports town.

These days, while the rivalry between Memphis and Nashville remains strong, the Grizzlies’ recent run of playoff success has helped dull the edge. They’re both big league towns now, albeit in different sports. There’s not a whole lot of Titans fandom in Memphis, despite the fact that Titans games block out any others in their time slot every Sunday. Pop into any given sports bar and you’re likely to see far more Patriots, Steelers, or Cowboys jerseys than Titans ones.

Maybe that’s because of some lingering bad feelings, or maybe it’s because of the fact of what Bud Adams never realized: Memphis and Nashville share borders, but little else. The hills of east Tennessee, the bright lights of Nashville, and the Mississippi River-fed Memphis are so distinct they might as well be three different states. There’s a reason that the state’s flag has three stars, after all.

“I have no doubt the NFL would have succeeded here, at least as you measure with attendance and bottom line,” Murtaugh says. “We want to call ourselves a basketball town, but this is a football region. Had there been no Tennessee Titans, had a franchise been located in Memphis, there’d be people flocking from Nashville westward.”

____

Jay Busbee is a writer for Yahoo Sports. Contact him at jay.busbee@yahoo.com or find him on Twitter or on Facebook.