August 11, 1994: Scenes from a lost MLB season

One day there was baseball.

The next there wasn’t.

This is the story of the day with baseball. The final day of games in 1994 was an odd day, one Major League Baseball had rarely seen before and one it hasn’t seen since. While a damaging strike looked unavoidable, no one still knew for sure if it was the last day of the season and so uncertainty ruled the day.

In many ways, it was a normal day of baseball on the field. Shutouts were thrown and home runs were hit. Teams moved up and down in the standings.

Away from it, however, it was anything but. Players packed their bags while divulging their plans for their time off. Fans filed through the turnstiles and waved signs asking for mercy on behalf of one of the greatest seasons they’d seen.

Tears were shed, tempers flared and minds were resigned to a sad fate.

The day was Thursday, August 11, 1994.

Riverfront Stadium: Cincinnati

9 a.m. ET

Hours before the most devastating strike in American sports history would begin, Ramon Martinez passed out cigars to teammates in the Dodgers clubhouse.

Major League Baseball players in 1994 were a united lot and they’d so far easily weathered the owners’ attempts to implement a salary cap. A war chest of $175 million built from baseball card royalties was available to get them through whatever stoppage lie ahead.

Yet Martinez and his co-workers were not celebrating the universal fortitude that would result in the cancelation of the first World Series in 90 years while also preserving their powerful union.

No, the cigars were for a much more common transaction. Martinez’s daughter had been born a few days earlier in California. After flying back west for the birth, Martinez hustled back to Cincinnati on Wednesday night. He had a start to make against the Reds the next day.

Knowing what we know now, no one would have blamed Martinez for staying with his family an extra day and then letting the strike extend his paternity leave at the stroke of midnight.

But his return underscored two realities for the 20 teams who were scheduled to play on the season’s final day.

No one knew for sure what would happen in the days and months ahead.

And because there were fans showing up and scores still being kept, no one was going to just mail the day in.

Yankee Stadium: New York

1:05 p.m. ET

As the Toronto Blue Jays and New York Yankees prepared to finish their series at Yankee Stadium, Toronto players’ rep Ed Sprague showed how impassable the situation had become.

“Really there’s no reason to have any meetings if the salary cap issue remains on the table,” Sprague said. “If it remains, there’s no point sitting in a room staring at each other.”

While labor issues had resulted in four stoppages over the previous 14 years, this fifth time loomed as the ominous final battle. The owners were bent on fitting the union with a salary cap straitjacket they’d disguised as a bid for competitive balance.

The players, meanwhile, were determined to ward off that attempt by damaging the owners’ bottom line as much as necessary. The Aug. 12 strike date had been selected judiciously as the players had already cashed a majority of their paychecks for the season. They were seeking leverage from the owners missing out on a payday from the postseason television contract — not to mention the damage that canceling the World Series would do to the game.

Yet that’s exactly where it was all headed as neither side seemed in a rush to resolve their issues. There were no scheduled talks between the two sides on Aug. 11, though both union head Donald Fehr and owner rep Richard Ravitch would meet that night on CNN.

Dodgers fan Larry King served as the go-between.

Eight teams had already played their final game a day earlier, leaving players unsure what was ahead. Some said they’d head home immediately; others said they would stick around the cities to see if anything got resolved.

In Oakland, White Sox shortstop Ozzie Guillen had joked that he was heading to work for owner Jerry Reinsdorf’s other professional sports team in Chicago.

“I’m going to be Benny the Bull,” Guillen said to reporters, referring to Michael Jordan’s rotund mascot friend. “I already asked Jerry and he said I could do it.”

Astrodome: Houston

1:37 p.m. ET

Guillen may have found humor in the situation, but most baseball fans did not. The greatest season many of us had ever seen was being threatened with an unsatisfying ending.

There were storylines abound. The once-lowly Montreal Expos were a powerhouse and owned the best record in the league. The Yankees looked resurrected after a decade of mediocrity while the upstart Cleveland Indians had a shot at making its first postseason since 1954. The league had just been split into six divisions and three of them featured two teams separated by a game or less at the time of the strike.

Individual runs at history were also in peril:

• Roger Maris’ single-season home run record of 61 was being threatened by San Francisco Giants slugger Matt Williams, who had 43 homers with 52 games left to play. Ken Griffey Jr. (40 homers) and a few others weren’t far behind.

• Frank Thomas of the Chicago White Sox and Albert Belle of the Indians were chasing the AL’s first Triple Crown since Carl Yastrzemski in 1967 while competing in a sizzling race in the AL Central.

• Minnesota’s Chuck Knoblauch had 45 doubles and a chance of breaking the record of 67 set by Earl Webb in 1931.

Then there was Tony Gwynn, the San Diego Padres hitting genius who stepped into the batter’s box in the top of the first to face Houston Astros pitcher Greg Swindell.

Gwynn’s average on the scoreboard read .391.

Every baseball fan had their eye on the batting average of the 34-year-old. His average climbed as high as .419 in mid-May and hadn’t dipped lower than .376 since. Becoming the first player to hit .400 since Ted Williams in 1941 was in play.

Gwynn would have needed a 6-for-6 day on Aug. 11 to hit .400 by the strike and that was unlikely, even for him. A 6-for-6 line has happened only 72 times in baseball history, none of them from Gwynn.

Still, there was no way he was going to head into the stoppage without a vintage Gwynn performance. He lined up the second pitch he saw from Swindell and hit a clean line drive into center field for a single.

His average ticked up to .392.

Yankee Stadium: New York

2:32 p.m. ET

Donald Fehr was in the news in 1994 as much as anyone not associated with the O.J. Simpson murder case and that was because he made himself visible.

With the strike now just hours away, the head of the players’ union made the rounds in the Bronx with reporters before the game and then did an inning in the MSG booth to state his side’s case.

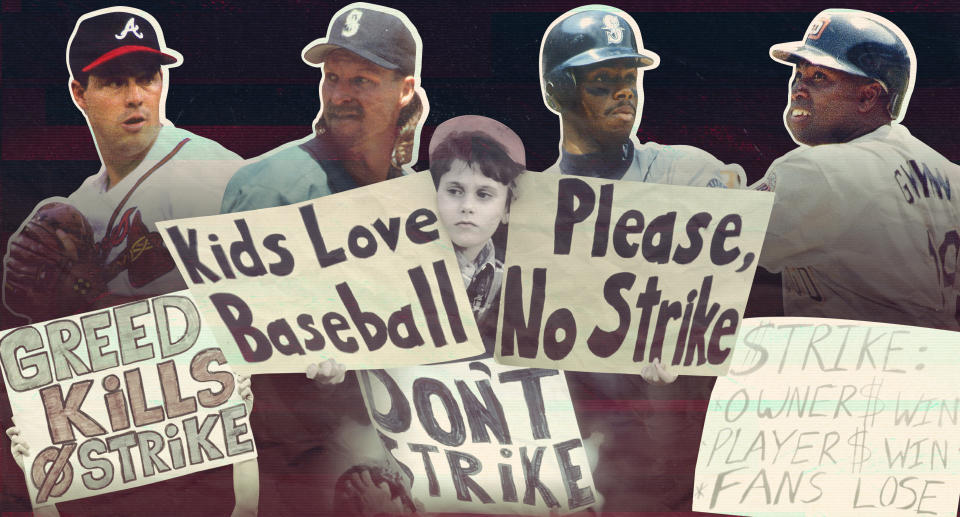

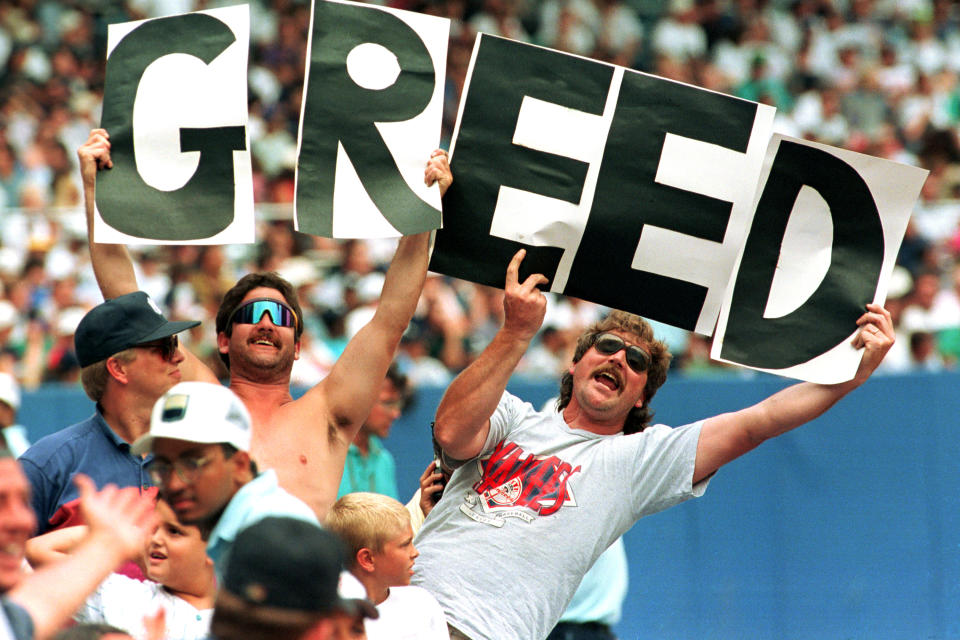

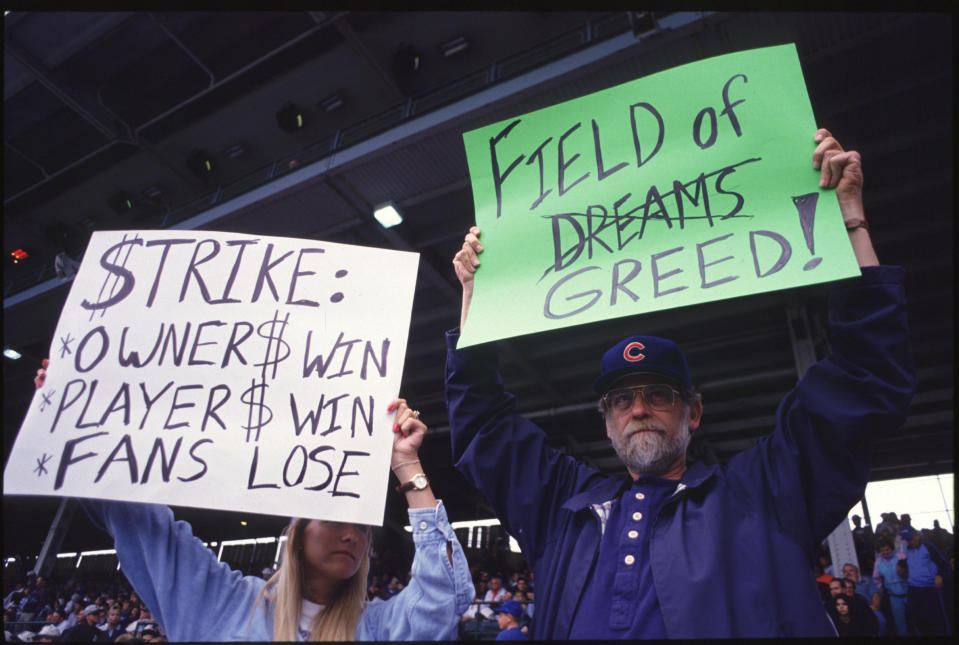

Fehr may have been trying to sway public opinion to the player’s favor, but it was an uphill climb. While there was no love lost for the owners, the players were the visible targets on the field and the ones who were going on strike. Fans labeled players as greedy and ungrateful for being afforded the opportunity to play “a kid’s game.” Heckles and signs were aimed toward them all summer.

“I will play shortstop for $20 a game or a case of Iron City!” read the sign of one thirsty fan in Pittsburgh.

Once Fehr was done with his appearance in the Yankees booth, he went to catch a cab. A horde of television cameras and print reporters followed him to the curb which is when a poetic “only in New York” moment happened.

According to an account in the New York Daily News, a grown man dressed in a clown suit appeared on the sidewalk, seemingly out of nowhere.

“Kiss and make up! Kiss and make up!” yelled the clown.

Fehr’s cab pulled away, leaving the clown and the media mob in a cloud of exhaust.

Riverfront Stadium: Cincinnati

2:58 p.m. ET

The first final out of the day fell into Brett Butler’s mitt on the warning track and the Dodgers ran onto the field to mob new daddy Ramon Martinez. He’d thrown a complete-game shutout in a 2-0 win while opposing starter Jose Rijo had struck out 12 batters over eight innings. Both teams would head into the strike occupying first place.

As “Happy Trails” played over the Riverfront loudspeaker, players from both sides disagreed on how long they’d be out.

“Right now it’s just an abstract thing that the season will be canceled,” Dodgers pitcher Orel Hershiser said. “I would say it’s a 10 percent possibility and 90 percent not possible. But the longer the strike goes, those percentages in change.”

Over in the Reds clubhouse, the outspoken Rijo took a blunter approach. Though the first-place Reds and Dodgers would be guaranteed playoff spots if MLB just came back for the postseason, Rijo didn’t foresee that happening.

“What have we clinched?” Rijo asked. “I think the season’s over.”

Rijo said he would be immediately returning to his home in the Dominican Republic and had some plans in mind.

“I’m gonna get in my Lazy Boy, get out my potato chips and popcorn and hope I don’t get too fat,” he said.

Yankee Stadium: New York

4:22 p.m. ET

“I heard it,” Don Mattingly would say later.

The Yankees and Blue Jays had reached the bottom of the 11th tied 6-6 when the fans who remained rose as one and cheered their way through Mattingly’s entire at-bat.

No one knew if this was Donnie Baseball’s final plate appearance and that stark fact increased the melancholy mood among Yankee fans. The team captain was 33 years old and battling the back problems that had plagued most of his career.

Mattingly had famously never been to the playoffs. He’d arrived in the Bronx in 1982 at the age of 21 just as the Yankees were coming off their 33rd American League pennant. But the regular playoff appearances were about to end. The Yankees would fall into a fallow period for the rest of the ‘80s with Mattingly often being the only draw.

The Yankees’ fortunes would soon change. On the final day of 1994, Mike Gallego wore No. 2 while playing shortstop for the Yankees. By the time baseball came back the following year, a new man owned the number (and eventually the position) while Gallego had unwittingly become the answer to a trivia question.

For now, though, Mattingly flew out to center field and the crowd finally sat back down.

Mattingly ended up returning in 1995 for one final season and reached his first playoffs.

Other players weren’t as fortunate. Among the big leaguers who would play their final games in 1994 were Bo Jackson, Jack Morris, Goose Gossage, Harold Reynolds, and Rick Sutcliffe.

Mattingly said he would’ve been OK had the strike placed him in that crowd and kept his career from the postseason.

“It was one of those times when you’re not thinking about yourself, but all the people who fought for you,” Mattingly said in 2019. “We wanted to preserve all the rights they’d fought for and we were enjoying at the time.”

Astrodome: Houston

4:37 p.m. ET

Sacrifice for the greater good was a theme among the stars who were having good seasons in 1994.

Tony Gwynn was no different than Mattingly. Though he had a chance to forever attach a .400 season to his name, he toed the party line and paid tribute to previous labor heroes like Curt Flood.

“People look at this [strike] as individuals not having a chance to break records,” Gwynn said to reporters. “But guys have sacrificed careers to make things better for a lot of young baseball players. Never in my wildest dreams did I think I’d get this close to .400. But as far as I’m concerned, getting an agreement is more important than hitting .400.”

Gwynn famously used only one bat during the 1994 season, a model he named “The Seven Grains of Pain.” It’d record two more hits against the Astros to go 3-for-5 on the day before being put away for the year. Gwynn’s final average sat at .394 — a number so iconic in San Diego it’s now the name of a popular beer.

Gwynn died in 2014 of salivary gland cancer and spent the rest of his life believing he could’ve hit .400 that year.

“I sure wanted the chance,” Gwynn later told NBC Sports. “I was squaring the ball up nicely, hitting lefties, righties. I would have given it a run. I’m not sure how I would have handled it in September. But I think I had the type of personality to handle it.”

Whether “Seven Grains of Pain” would’ve made it the whole way is up for debate. The bat shattered in batting practice soon after the players returned for the next spring training.

Veterans Stadium, Philadelphia

4:45 p.m. ET

Bobby Bonilla was the New York Mets players' rep in 1994. But if playing nice with the media and trying to curry favor was in the job description, the star slugger apparently didn’t get the memo.

As the Mets prepared to play the Philadelphia Phillies, Bonilla found himself toe-to-toe with television reporter Art McFarland in a confrontation you can now find on YouTube.

“Get that f----- microphone out of my face before I shove it up your ass as far as it can go,” Bonilla told McFarland.

To his credit, McFarland didn’t flinch. The reporter’s mistake, Bonilla believed, was to keep asking how much money Bonilla would lose over the course of the strike. As the owner of a five-year, $29 million contract, the math worked out to $31,146 per day — though it’s unclear how his famous deferred payments affected that total.

Emotions were running high and Bonilla and McFarland wasn’t the only athlete-media fight taking place. In Pittsburgh, Pirates center fielder Andy Van Slyke apologized to radio host John Corby for an exchange that Corby had interpreted as a threat.

Earlier in the week, Corby had called the players “lunatics” on-air and Van Slyke had responded by telling Corby to be careful coming out to Three Rivers Stadium.

“He said he was only giving me some advice that balls and bats can sometimes get away from players,” Corby said. “I don’t like to think I can be abused.”

Mile High Stadium: Denver

5:08 p.m. ET

If baseball fans were being turned off by the impending strike, they weren’t showing it at the turnstiles. The official announced attendance for the final day’s nine games was 291,234 — a total that didn’t include the 47,000 or so fans who packed Camden Yards for an Orioles-Red Sox game that was called due to rain in the third inning.

Out west, the Colorado Rockies were in the second year of their existence and heading toward another attendance record while playing in spacious Mile High Stadium. After attracting an all-time high 4.5 million fans in ‘93, the Rockies were on pace to pass that mark with a full slate of home dates in ‘94.

That would never happen, of course, but 65,043 fans dutifully filed in for one final matinee against the Atlanta Braves.

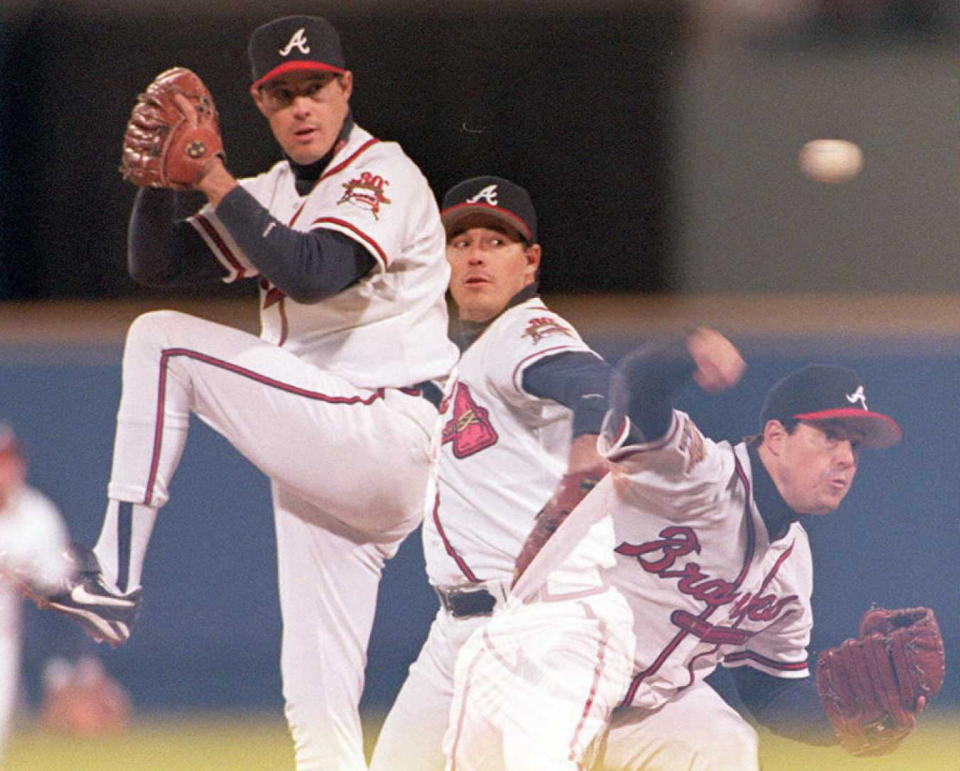

On the mound for Atlanta was Greg Maddux and if no one laments about his lost 1994, it’s only because he’d normalized his insane production and would reach similar heights again. He’d won the last two NL Cy Young awards and was on his way to a record third in ‘94. He’d win a fourth straight in ‘95, too.

Maddux came into the game against the Rockies with a 15-6 record and a 1.63 ERA with nine complete games over 24 starts.

But he wasn’t done just yet.

Maddux’s numbers were about to get even better.

Tiger Stadium: Detroit

7 p.m. ET

The Milwaukee Brewers and Detroit Tigers were having forgettable seasons and both would have undoubtedly liked to get their game over as quickly as possible.

Mother Nature had different ideas and the afternoon start was delayed almost three hours due to rain. Players passed their time in the clubhouse playing cards and speaking with reporters working on their angles.

“I thought I’d be looking forward to this day,” Tigers outfielder Tony Phillips said. “But it’s a really sad day.”

Over in another corner, a journeyman pitcher named Mike Gardiner wondered how the players had come to be viewed as the villains. While other colleagues were making millions, the 28-year-old Gardiner said he wouldn’t be able to absorb the loss of a paycheck as easily as others. His annual salary was $150,000. His career would be over the following year, never having cracked $200K a season, let alone seven figures.

“I don’t have a lot of money to throw around,” Gardiner said. “We’re not all millionaires.”

The game finally started just after 4 p.m. local time and took a shade under three hours. Both teams would finish with identical 53-62 records after the Brewers rallied for six runs in the eighth inning for a 10-5 victory. The announced attendance was 18,857 people though there’s no telling how many made it until the end.

“Before the game, I wondered if it was worth the wait,” Tigers manager Sparky Anderson said. “After that eighth inning, I think that must’ve been going through everybody’s mind.”

Three Rivers Stadium: Pittsburgh

7:35 p.m. ET

As his team prepared for a four-game sweep attempt of the Pirates, Expos manager Felipe Alou lamented his situation.

“I feel like the fisherman who has made a record catch but has to throw the fish back,” Alou said.

Much is still made about the ‘94 Expos and everything that was lost. And for good reason. The team was a powerhouse with a lineup made of players who were all under 30. A core including Larry Walker, Moises Alou, Marquis Grissom, and Cliff Floyd had the team on track for 105 wins.

Yet it’s sadly fitting that the ‘94 Expos would end their season with a loss. On this night, they’d manage only five hits as Pittsburgh Pirates starter Zane Smith fired a complete-game shutout in a 4-0 win that took a tidy two hours and 23 minutes.

Afterward, a 22-year-old Pedro Martinez, who’d won his last five starts, tried to stay optimistic.

“I think everything will be over before we think,” he said.

Up in Montreal, a 19-year-old named Scott Charpentier kept similar hope alive. A newspaper reporter spied Charpentier buying three tickets for the next day’s Mets game at Olympic Stadium — a long shot considering the two sides weren’t anywhere close to resolving their differences.

Charpentier was still insistent that the strike would be resolved by the following night.

And if not?

“I’ll probably frame the ticket on the wall as a souvenir,” he said.

Denver: Mile High Stadium

7:45 p.m. ET

Greg Maddux induced a groundout to third from Dante Bichette and another game was in the history books. Despite the Braves offense exploding in a 13-0 win, the game had only taken two hours and 37 minutes to complete.

Maddux was the day’s star, pitching his 10th complete game and lowering his ERA to 1.56. He’d also pitched in at the plate, going 3-for-5 and plating his first two RBIs of the year.

But if the Braves ace was disappointed about pausing a great season and a fourth straight playoff run for the franchise, he wasn’t letting on. He said he planned to fly home solo to Las Vegas instead of heading back to Atlanta with the rest of the team.

“I guess everyone looks forward to not going to work, no matter what job you’re in,” Maddux told reporters. “It’s weird, it feels like the last day of the season. I remember when I was with the Cubs, it was like this.”

Someone pointed out to him that he’d be missing out on $22,099.47 a day during the strike. But Maddux demurred.

“I’m not worried about that,” he said. “I’m just worried that we strike right … we have to be smart.”

Joe Robbie Stadium, Miami

9:41 p.m. ET

Rain brought an early end to St. Louis’ 8-6 win over the Florida Marlins. But the most noteworthy aspect of the Cardinals’ final day of the season was just beginning.

Team president Stuart Meyer told player rep Todd Zeile just a day earlier that the players would have to find their own way home from South Florida. With the owners and players now at war, the Cardinals team charter would only be available to coaches, broadcasters and support staff.

Though the Cardinals saw their decision as justified, the move came as a surprise. St. Louis was only one of two teams (the Mets were the other) to put the players out in such fashion and it embittered them. Zeile scrambled to find a charter for his colleagues; the $18,000 cost was split among the group.

And so, in the early hours of the strike’s first day, St. Louis’ Lambert Airport played host to a surreal scene. The Cardinals team plane arrived with manager Joe Torre and a few others around 2 a.m. The players charter landed about a half-hour later.

“I was disappointed in the organization,” Zeile said. “There was no real reason to do this, except to kick dirt in the players’ face.”

The team’s response was far from apologetic.

“It isn’t a friendly situation any more, it’s a fact of life,” Meyer said. “It’s a business decision based on the players trying to hit the owners at the toughest time for the biggest financial loss.”

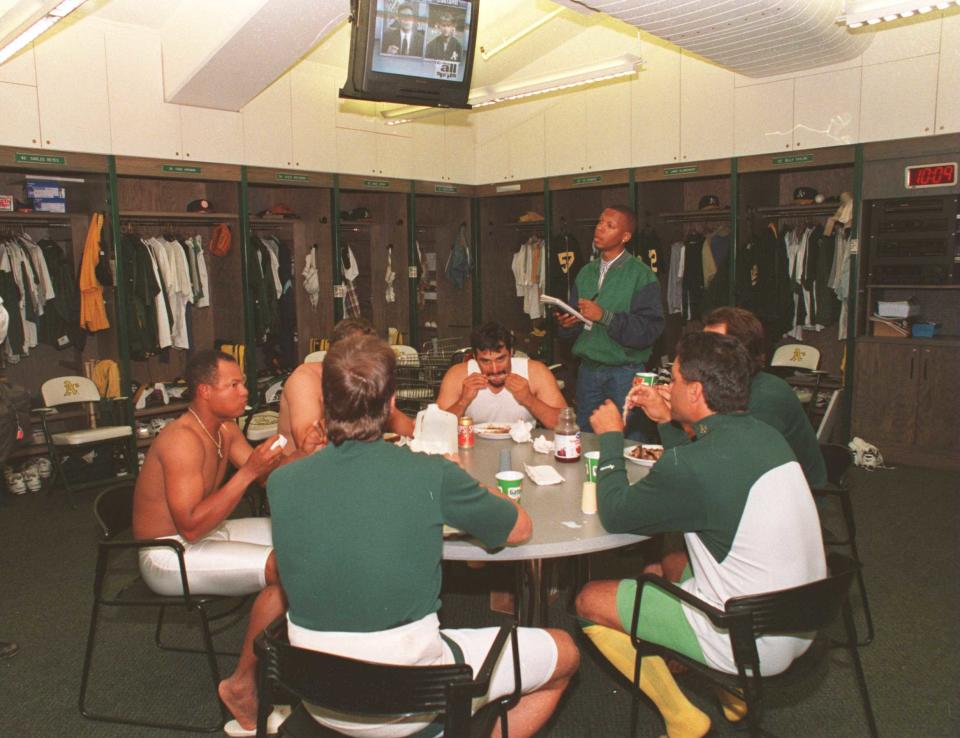

Oakland Coliseum, Oakland

10:07 p.m. ET

There was no debate that baseball’s biggest star in 1994 was Ken Griffey Jr. The Seattle Mariners superstar had received a record 6 million votes for the All-Star Game earlier in the season and was a marketer’s dream. As the strike loomed, he stood back to back with Frank Thomas on the Sports Illustrated that currently sat on newsstands across the country.

“Two powerful reasons to keep playing ball,” read the cover

Everyone wanted to see what Griffey would do next and there was no shortage of ways he could do something you’d never seen before. His slash line coming into the Mariners game against Oakland was .322/.400/.669 with 39 homers, 86 RBIs and 92 runs. Unreal totals for a full season, let alone one with almost two months left.

And yet it seemed clear that Griffey’s numbers were about to be frozen in carbonite, never to be thawed.

“I picked a bad year to have a good year,” he said.

Reporters asked Griffey his plans for the strike and his response was incredibly on-brand for 1994. The 24-year-old would go to MC Hammer’s house in the Bay Area to play air hockey and video games before driving back to Seattle.

Griffey’s performance that night was even more on-brand. He started the day by making a great catch on the track in the bottom of the first, robbing Stan Javier of extra bases.

He then hit a grand slam off Ron Darling in the top of the second inning. It was his 40th and final home run of the year.

Veterans Stadium, Philadelphia

11:28 p.m. ET

The late West Coast start time made it seemed destined that the A’s and Mariners would be the last game completed. But the Mets and Phillies made a late run at that honor, stretching their game to 15 innings before 37,605 people in Philadelphia.

Finally, as the rain came down on Veterans Stadium, Ricky Jordan singled off Mario Gozzo to score Billy Hatcher.

A year earlier, the Phillies season had ended in walk-off fashion when Joe Carter hit his home run off Mitch Williams in Game 6 of the 1993 World Series. Now the next Phillies season had ended with them on the right side of a game-winning hit and yet the feeling was just as empty.

In the clubhouse, Lenny Dykstra pulled on a cigarette before delivering an epitaph in Dykstra-esque fashion.

“Dude, this really sucks,” he said.

“We knew it was coming for two years,” he continued. “But you keep thinking something will happen and that the strike won’t happen. But, boom, here it is, man.”

Oakland Coliseum, Oakland

12:45 a.m. ET (Aug. 12)

The final pitch of the 1994 season was a Randy Johnson fastball, fired 45 minutes after the strike deadline on the East Coast. It blew past Ernie Young, who went down on three strikes for the third out of the ninth inning.

It was Johnson’s 15th strikeout of the game. After an uneven start to his career, he’d blossomed in recent years and was almost ready to blast into a Hall of Fame stratosphere that would see him win five Cy Young awards.

But like everything else in baseball, it would have to wait. The strike would last 232 days, cancel 948 games and cost the owners about $580 million in revenue. The Expos would never reach the playoffs, the marks set by Roger Maris and Ted Williams would remain untouched.

The game’s reputation, meanwhile, took a big hit with fans when the rest of the season and the World Series was called off on Sept. 14. While spectacles like Cal Ripken and the Big Mac-Sammy home run chase would grip the nation’s attention, the game has arguably never quite recovered from the damage it brought onto itself in 1994.

Whether or not the players fully realized this at the time is up for debate. What they did know was that there was a line to be held and they were willing to hold it like they had before.

"I've been through this four times already,” Rickey Henderson said in the Oakland clubhouse. “Go talk to the young guys. I'm on vacation."

Anaheim Stadium, Anaheim

Postscript

The Angels did not play on Aug. 11, but they were scheduled to leave for Detroit for a weekend series. Though a strike looked imminent, the team still pulled two buses up to the stadium. The team’s clubbies came out and quickly loaded them with equipment for the road trip. Bats and gloves, catcher’s equipment and uniforms. Manager Marcel Lachemann, a six-man coaching staff, trainers and the PR guy arrived. They all climbed aboard and waited for the trip to the airport to begin.

Yet not a single player showed up. The buses never pulled away from the stadium. The scheduled plane never took off.

“We were just following our itinerary,” Angels GM Bill Bavasi said at the time. “We figured that if they didn’t show up for the plane, the strike was on.”

Editor’s note: This article was written using contemporary articles from the Associated Press, Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati Enquirer, Detroit Free Press, Los Angeles Times, New York Daily News, Philadelphia Inquirer, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, The Press Democrat and The Sun-Sentinel.

More from Yahoo Sports: