The amazing story of the greatest AAU team you've never heard of

NEW ORLEANS – Of all his earthly possessions lost to Katrina’s flood in 2005, the one Richard Coffey wishes he had right now is a program from a long-ago basketball tournament. For years he had kept the program as proof that once he was part of a magnificent teenage team – one so good that 37 years later he breathes his teammates’ names as if the whole thing had been a dream.

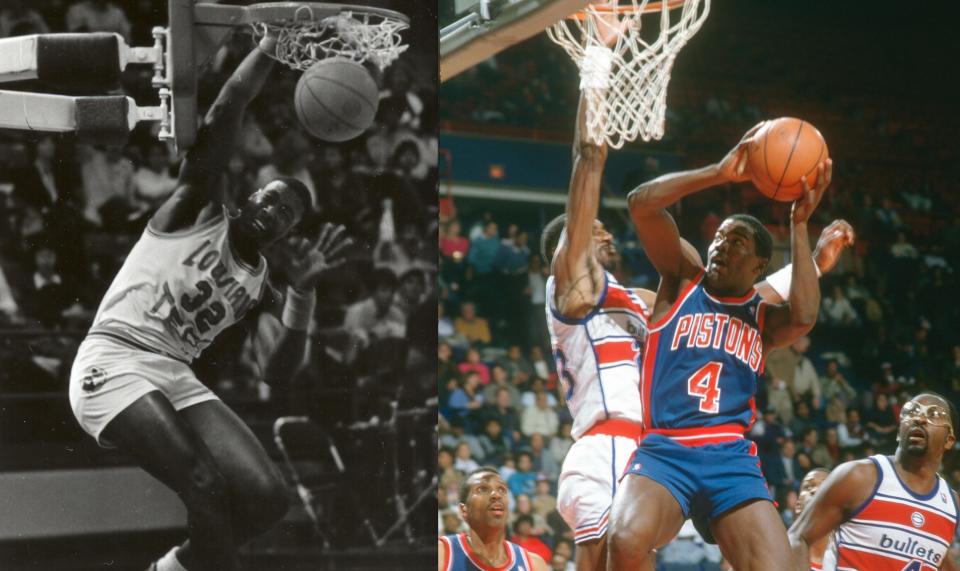

Karl Malone.

Joe Dumars.

Hot Rod Williams.

Benny Anders.

“I don’t think anybody would believe I played with those guys,” he says.

Back in the summer of 1980 there was a Louisiana AAU team of 15- and 16-year-olds almost too amazing to be true. Among those on its roster were two future Hall of Famers (Dumars and Malone), a player who would become one of the NBA’s best shot-blockers (Williams) and another (Anders) who turned into the most dazzling player on a college basketball dunking sensation known as Phi Slama Jama. It was the kind of team that caused heads to turn and the rat-a-tat-tat of dribbling to stop the moment its players walked into a gym.

Even today, Guy McInnis, a guard on the team, chortles as he recalls the silence that greeted them.

“We weren’t even trying to be intimidating!” he says.

But how could they not terrify? Imagine the alarm that must have blared through a high school junior’s brain as he watched a young Malone, already 6-foot-8 and chiseled from years on the farm, dunking so hard that he shook the walls of tiny gyms? Who wouldn’t stare, slack-jawed, as Anders, just three inches shorter than Malone, dribbled behind his back, then took off from the foul line hurtling toward the rim?

The Louisiana team’s players were strong and fast and played ferocious defense. Their coach, an old-time grinder from the northwest part of the state, drove them to run, run, run. Sometimes, it seemed, they won simply by showing up. Though no official record of that summer exists, the players remember dominating nearly every game they played around Louisiana or in the two national tournaments they entered. Most of those victories were blowouts. Once they scored 224 points over two games – in the same day.

And yet this wasn’t some roll-out-the-ball-and-go-play kind of AAU team. Louisiana’s players worked hard, practicing twice a day in sweaty gyms, some of which had slippery vinyl floors. The best of them weren’t superstars dripping with entitlement but country kids barely known by college recruiters. Dumars, Malone and Anders came from small towns in the north. Williams grew up in a trailer just off the road from New Orleans to Baton Rouge. A few lived in rural Mississippi. Most of the rest were white teenagers from the New Orleans suburbs. Separating them were hundreds of miles of backwoods roads and a racial and social makeup like none on the other teams they played.

“Anything people think of when they think of an AAU team – this team was the opposite of that,” says Dumars.

Except for its extravagance. In many ways, the Louisiana team exceeded the opulence of even modern AAU clubs. That’s because it was the invention of a wealthy businessman, Robert Thompson, the president of First Progressive Bank near New Orleans, whose son, Bobby, was a promising player at a small high school in the city. Hoping to challenge Bobby, the elder Thompson put together a local AAU team during Bobby’s sophomore year in 1979, later merging it with another in Baton Rouge to form a statewide super club.

That’s when things really got crazy. What followed were three ridiculous years of the First Progressive basketball team with its own corporate jet, an impromptu romp through a Vegas casino and – for three months in the summer of 1980 – the greatest AAU basketball team you never heard of.

Time has dulled some memories. Piecing together the story of First Progressive’s 1980 summer team is not easy. Williams died in 2015. Anders has detached from old friends and wants to be left alone. Malone – through an intermediary – rejected several interview requests. Some players appear to have disappeared, not replying to last-known numbers or emails. Still, enough people from that team could be found who recall those three months and the thing that it gave them the most.

A chance.

“None of us knew what our futures were at that point,” Dumars says. “Just getting to travel around like that was a big deal. We were guys from Louisiana and this was an opportunity of a lifetime. We were just happy to play together.”

This is the story of their team in eight parts.

Part I: They even had their own plane

What kind of AAU team has its own private jet with leather seats?

This one did.

Technically, the plane didn’t belong to the team, it was owned by Popeyes, the fast-food chicken chain based in New Orleans. But Robert Thompson was close to Popeyes owner Al Copeland, who allowed Thompson’s team to use the jet when necessary. This was important because the First Progressive team had two bases: Bobby Thompson’s Ganus High in New Orleans and Louisiana Tech, four hours to the north in Ruston. Half the practices and games were at Ganus, the other half, along with a two-week training camp, were at Louisiana Tech. Sometimes everyone drove back and forth. But why drive when you can fly in a private jet?

“You think back on it now and you say, ‘That’s crazy we had a plane,’ ” McInnis says. “At the time, if you were late and needed to get to practice, it didn’t seem so strange.”

But it was crazy and it was strange. Even in today’s world of supercharged AAU teams where coaches have secret deals with agents, players aren’t normally whisked around in private jets. Such a thing was unheard of in 1980. And people were flabbergasted when word rippled through AAU circles about the Louisiana team with its own corporate jet.

“Yeah, it was mind-boggling,” Bobby Thompson says, laughing as he sits in a New Orleans hotel restaurant, a man now in his 50s with graying hair and a still-muscular build. “Then again, we were ahead of the curve.”

Mostly they were beneficiaries of Robert Thompson’s extravagance. The elder Thompson was well known around New Orleans in those days, the former head of the powerful Superdome Commission. He had money and influence and was willing to show it. He gave players rides home in his Lincoln Continental, calling their parents from the road if they were going to be late. “He was the first guy I knew who had a car phone,” says one of the other New Orleans players, Jeff Wenzel, a rugged 6-foot-6 forward who later had a brief NFL career.

For the players, many of whom had barely been away from their hometowns, flying in a corporate jet, even just between Ruston and New Orleans, must have felt like zooming to the moon. Dumars, who grew up in tiny Natchitoches near the Texas-Louisiana border, spent much of his childhood in the town’s libraries reading about the faraway places he assumed he’d never see. Suddenly, at 16, he was zipping about in a private plane at a time when even movie stars and pro athletes didn’t do such things.

“I’m pretty sure the first time I ever flew was on a private jet,” Dumars says.

Which, if you think about it, is pretty remarkable.

Part II: In which one of the greatest power forwards in NBA history was throwing hogs

Nothing, though, might have been as incredible as the day McInnis met Malone. This was late in the spring of 1980, and McInnis was with a group of teammates picking up players for training camp in Ruston. They drove onto the farm where Malone grew up and were greeted by Malone’s mother, who sat on the porch. She said little to her visitors but when her son came out carrying his bags she yelled at him about unfinished chores. She said he was going nowhere until he moved the hogs.

Near the house were two pig pens separated by a walkway. Apparently Malone was supposed to have transferred the hogs from one pen to the other and neglected to do so. As McInnis and the other players watched from the car, Malone rushed to get his hogs across the walkway. It was an arduous task, and the longer it took the angrier he became.

“He was so mad he was picking the pigs up and throwing them across the walkway into the other pen,” McInnis says, laughing. “I had never seen anything like it.”

But that was the wonder about First Progressive in the summer of 1980. Everything was a new adventure. Its players came from remarkably distinct backgrounds and experiences. The kids from the country had almost nothing, while those from New Orleans were well-to-do. This team hadn’t seen much of the others’ world until suddenly they were thrust in the middle and forced to adjust.

Bobby Thompson, in particular, was conflicted. He had grown up comfortably, able to have anything he wanted and suddenly he was teammates with players who had nothing. He was shocked to discover that a forward from a different First Progressive team had been raised in a shack with an outhouse. He had no idea people still lived that way, and burned forever in his mind is the look of amazement on the player’s face the first time they stayed in a hotel and the player saw a room with its own bathroom and flushable toilet.

Years later, when Thompson and Williams played in college at Tulane, Thompson sometimes caught himself glancing at Williams, who forever smiled despite his poverty, and he’d shake his head.

“Here I was growing up with a silver spoon in my mouth and a Trans Am in my driveway before I even had a license, and I was sitting next to guys on the bench who grew up without running water,” Thompson says. “It was hard for me to imagine what it was like for them.”

And yet by all accounts they enjoyed each other. Nobody recalls any fissures or cliques. No one fought. There were no running feuds. They might have come from opposite worlds, but they were united in two-a-day practices and the freedom that comes with being 15 or 16 and away from home for the first time.

“There were no egos,” Dumars says. “I think what would have stood out was if someone had a big ego. At a certain point we all were dedicated to just trying to make it. That was the bond between us. There was not an option for us not making it. For us this was an incredible opportunity. You were thankful to be selected for the team and it was the opportunity of a lifetime. Who knew if something like this would come again?”

During the Ruston camps, they lived in Louisiana Tech’s dormitories and bounced between rooms as Kurtis Blow and the Sugarhill Gang blasted from boom boxes. Someone had a television and at night they watched baseball. Other times they rolled dice and chased girls. Thompson even remembers trying moonshine brought by a player from up north.

On the weeks the practices were held in New Orleans, Robert Thompson got rooms for the out-of-town players at the posh Fontainebleau Motor Hotel, famous for its giant resort-style swimming pool. After practice, everyone, including the local players who stayed at home, went to the Fontainebleau for barbecues and swims in the pool.

Aside from Malone, who talked endlessly about farm life and 18-wheel trucks, Anders was the loudest. He carried with him the pedigree of being the cousin of NBA stars Willis Reed and Orlando Woolridge as well as his own nickname, The Outlaw, which seemed to be a self-proclaimed title. He wore it everywhere as former LSU coach Dale Brown found out when Anders showed up for his official visit in a jacket with “The Outlaw” printed down one sleeve.

“Oh, my God, man, he had a huge personality,” Dumars says. “He had the biggest personality on the team. He was just a supremely gifted guy. … It was just so rare to see a guy 6-foot-4, 6-foot-5, handling the ball like a point guard and bringing the ball up at that time.”

While Anders had a bothersome habit of mocking the players upon whom he dunked in practice – his teammates liked him. Even Brown, who was turned off by “The Outlaw” jacket, says Anders was “polite” and “respectful” on his LSU visit. ESPN’s “30-for-30” on the University of Houston’s Phi Slama Jama suggests that Anders was burdened by his basketball pedigree, tormented by the pressure of living up to the legacy of Reed and Woolridge. Many of the First Progressive players suspect his flamboyance was a front and that the real Anders was far more sensitive.

“I know he was called ‘The Outlaw,’ but I think he was misunderstood,” McInnis says. “That was part of his persona, but I think he was a good guy.”

Williams, who did not join the team right away, never seemed a huge part of the group. This might have been because he grew up with so little. Players remember him as quiet and wonder if his childhood in the trailer might have left him socially detached from the others. Despite his silence he had warmth that made the others all like him. “I don’t think I ever saw him without a smile on his face,” says Wenzel, who later played football at Tulane when Williams was a basketball star there.

Looking back now with decades of racial and cultural experiences, some of the players sound surprised as they recall how well everyone got along. Their backgrounds really were diverse and it would have been easy for kids like Malone or Williams to resent someone like Bobby Thompson, just as McInnis or Wenzel might have looked down on Anders or one of the Mississippi players. Still, that never seemed to have happened. Some of them wonder if this was the result of being thrown together for days in a place where they knew no one else. Others suspect it was because they were so young they had yet to develop prejudices that sometimes come with age. They might just have had the right mix of personalities, too.

But there was also an incident, something so jarring to the white players that it still troubles them today and it opened their eyes to what life was like for their black teammates.

Part III: The officer on Highway 1

One afternoon, a group of players, including Wenzel, McInnis, Thompson and Dumars, was traveling in a car between Ruston and New Orleans. Though no one remembers who was driving, they do recall Dumars was the only black player in the vehicle and that he sat in the front passenger seat. At some point, on a remote stretch of Highway 1, they passed a police officer who glared at the car before pulling it over.

When the officer approached the car, however, he didn’t come to the driver’s window. Instead he walked around to the passenger door and ordered Dumars out. He looked angry and led Dumars behind the car where he began firing questions. Who are you? Where are you going? Why are you in this car?

Dumars picked his answers carefully, calmly explaining they were part of a basketball team on its way to a tournament. All the while he held his breath, terrified he was about to be hit.

“This guy looked ready to react at the drop of a hat,” he says.

Inside the car, the white players sat numb. Dumars was probably the most mature and social of them all – always carrying a tiny green Bible from which he could relate a parable to any situation. He was the teammate who could talk to anyone, forever curious about each player’s interests, filling his conversations with questions. They had come to see him as the one who could talk about anything: worldly without yet seeing the world. Years later, Richard Stanfel, a center on the team whose father, Dick, was a Hall of Fame football player and briefly the New Orleans Saints’ coach, would call Dumars “the glue that held those guys together.”

He was the least likely of them to be in trouble and yet here he was on the side of a country road being interrogated by a police officer who appeared ready to beat him.

The players wondered what it was that made this man so angry. They were driving fast but not faster than anyone else on the road. They hadn’t been drinking or smoking or doing anything else that might have drawn attention. Was the sight of a black teenager riding in a car with white teenagers really enough to enrage the cop? They had never been confronted with racism like this in their suburban lives.

“It was like one of those things where you were like, ‘Oh, man,’ ” Wenzel says.

Eventually, Dumars returned to the car. The officer waved them on. For the next several miles no one said a word.

“Let me tell you what, that was an eerie feeling,” McInnis says.

“For those guys it probably was unsettling,” Dumars says. “But even for me who had dealt with it before, that was scary. For him to go to the passenger side, to the only African-American kid in the car and pull me out and give me the third degree, that was unnerving. I had no idea what he was going to do. It’s something you don’t ever forget.”

Part IV: A ‘good ‘ol country-boy coach’

To coach his team, Robert Thompson hired Clyde “Buster” Carlisle, a hard-driver from the small northwestern Louisiana town of Minden. Carlisle was not the type you’d normally associate with a star-filled AAU team. He had close-cropped hair, a rural accent and an aversion to modern methods of hydration. “Water rusts pipes, water is bad for you,” was one of his favorite sayings.

Carlisle’s practices were long and involved lots and lots of running along with exercises that were almost diabolical. In an early training camp practice, McInnis found himself matched with Dumars for one of Carlisle’s most sadistic drills: a two-on-two full-court game with no rules or decorum. Their opponents were Benny Anders and Anders’ high school teammate, Bernard Payne, who briefly played for First Progressive. On the first possession, Payne knocked McInnis to the floor, grabbed the ball and took off down the court for a dunk. McInnis glanced at Carlisle expecting a whistle. The coach said nothing.

What followed, McInnis says, was “a war,” with bodies flying as the two pairs shoved each other all over the floor. Eventually, McInnis and Dumars won. As they headed toward the fountain for a rare water break, McInnis noticed Anders and Payne angling behind them. He could see they were seething. He stiffened, anticipating a punch, when suddenly Malone appeared from behind.

“There will not be any fighting!” Malone boomed.

“It was cowboy, man,” McInnis says.

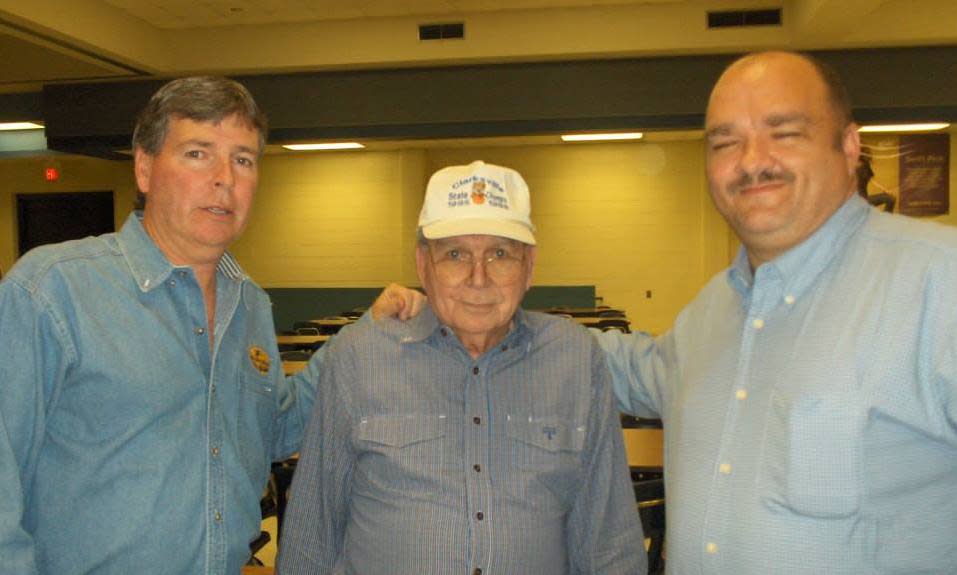

But that was life playing for Carlisle. The coach was ground hard like a drill sergeant with a belief that the end justified his means, and it is hard to argue with his 1,103 wins over 41 years at Louisiana and Texas high schools, which were reported at his 2014 death to be the fourth highest for a high school coach nationally.

“He was, for a lack of better words, a good ol’ country-boy coach,” Wenzel says. “He knew basketball inside and out and didn’t mince words. If he had it in his head he would tell you.”

Carlisle adored Bobby Knight, and like Knight he loved nothing so much as a relentless man-to-man defense, dedicating hours of practice to teaching it … in a very Knight way.

“He’d say, ‘Listen boys, have you ever been in the woods and had to take a dump before?’ ” Thompson says. “ ‘If you don’t crouch deep, all that stuff is going to run down your leg, but now if you get a good defensive stance then you’re good.’ ”

And yet as insane as Carlisle might have seemed in practice, the players found him otherwise pleasant. He let Coffey – a gifted outside shooter in pre-3-point days – fire at will and seemed amused by Malone’s physical dominance. He often gave rides to the players from the north, driving them down to New Orleans when they didn’t have use of the Popeyes plane. He brought his 10-year-old son, John, everywhere and the boy became a favorite of the players, who often let him join in their drills.

Now in his 40s and coaching in Texas, John Carlisle can still remember Dumars and Malone babysitting him at times when his father was busy, as well as Malone’s mother instructing his father to “get on” her son “if he acts up.”

“Dad was friends with the kids off the court, but on the court it was all business,” John Carlisle says. “He was a mentor to them.”

All he asked for in return was that everyone practice hard, which they did.

Until someone didn’t.

Part V: In which the greatest AAU basketball team you never heard of parted ways with a future third overall NBA draft pick

As loaded as First Progressive was that summer, it could have been better. For a few days at training camp, the team also had 7-foot center Benoit Benjamin from Carroll High School in Monroe. At the time, Benjamin was perhaps a better-known prospect than Dumars and Malone – a towering center who already had college coaches chasing after him.

Everybody knew Benjamin was good, and he would be the third overall pick in the 1985 NBA draft. It wasn’t hard to imagine the power of a frontcourt that included Malone, Williams and Benjamin. With him, First Progressive might never have lost a game.

But Benjamin didn’t want to run much in practice and if you didn’t run in practice you weren’t going to play for Buster Carlisle. Several players remember him either jogging down the court or refusing to run at all. Stanfel can still see Benjamin leaning against a basket stanchion while the rest of the team ran wind sprints.

“My dad wouldn’t put up with that,” John Carlisle says. “If you didn’t run, he would cut you.”

It wasn’t clear to many of the players whether Benjamin was cut or simply quit. Some remember Carlisle dropping him, others insist Benjamin left on his own. “He didn’t seem to be into it,” Coffey says. Either way, he was soon gone and the rest were left to ponder the eternal question of how great a five of Dumars, Malone, Williams, Anders and Benjamin might have been.

“Can you imagine cutting a 7-footer from an AAU team?” Thompson asks. “But that’s how strong this team was.”

Part VI: Did he say Las Vegas?

Believe it or not, the Dumars, Malone, Williams and Anders team was not First Progressive’s best – at least not on the court. That would be the Summer of 1979 team, which stuck together through the spring of 1980. McInnis and Bobby Thompson had just finished their sophomore years and were surrounded by older players who were more polished prospects than Dumars and Malone would become a few months later. The 1979 team’s two top stars – future Louisville center Charles Jones and guard Johnny Jones, who eventually became a player and coach at LSU – were lusted after by what seemed like every elite college coach. Just how much became clear in April 1980 at the Basketball Congress International Senior Prep Tournament in Tucson, Arizona, the western version of an AAU championship.

The tournament was designed to be a showcase for high school senior prospects – recruiting was simpler back then – and the college coaches were everywhere. UNLV’s Jerry Tarkanian came carrying shoes with the Runnin’ Rebel logo. Louisville’s Denny Crum kept showing up at breakfast in his pursuit of Charles Jones. Lute Olson, then at Iowa, had to be chased from his future home gym by Carlisle, who caught Olson talking to Johnny Jones before a game.

“We got shoes and warmup suits and everything,” Thompson says. “Everything they weren’t supposed to be giving us, they were giving us.”

To further inspire Crum and the other coaches’ desire, Charles Jones won the dunk contest by picking up a ball with each hand, leaping straight in the air and shoving them through the rim, one after the other.

“That brought down the house,” McInnis says. “Tark was jumping up and down, high-fiving people in the stands. It was unbelievable.”

First Progressive made the championship game and then went cold. At halftime, with his team trailing, Robert Thompson walked into the locker room and said: “If we win we are going to Las Vegas.” Then he left. McInnis and Bobby Thompson remember everyone looking at each other with the same bewildered expression.

Did he say Las Vegas?

First Progressive stormed back to win the title as the players left the court chanting: “Las Vegas! Las Vegas! Las Vegas!”

“Johnny Jones was leading the cheers in the van [to the airport] after we won it,” Bobby Thompson says. “He probably didn’t think it would happen.

“It happened.”

They flew to Las Vegas and were whisked to the Sands Hotel and Casino, where minutes after checking in, John Carlisle peeked out his window to see Tarkanian heading into the hotel to continue recruiting First Progressive’s players. No one could figure out how he knew they were there. That evening they went to see Wayne Newton, who called them on stage. Later, Robert Thompson gave the players each $100 with instructions to not leave the hotel. They spent the night running the building, clutching more cash than most of them had ever seen, amazed at the world swirling dreamily around them.

“What a night that was. We won the national championship and then went to Las Vegas,” McInnis says, shaking his head.

He stops. A small smile slides across his face.

“Come to think of it,” he continues, “you have a kid and he goes to Tucson for a basketball tournament and the team was supposed to come home and then they didn’t come home and then they’re in Vegas …

“What were my parents thinking?”

Part VII: The best AAU team you never heard of might have been too good

There were no surprise trips to Las Vegas for the summer of 1980s team. No handshakes with Wayne Newton. No romps through the Sands with Jerry Tarkanian sneaking in the front door. The team of Dumars, Malone, Williams and Anders actually might have been too good and too deep to win a national championship. Carlisle compounded this problem by trying to play everyone as equally as possible – a democratic gesture, but not the best formula for winning.

To ensure fairness, the coach created two lineups: one that played the first and third quarters, and another that played the second. He mixed things up more in the fourth. Nobody much remembers who started and who came in during the second quarter, but Carlisle told the players he wanted both rotations to be balanced. A New Orleans Times-Picayune story previewing that summer’s AAU Junior Olympics, which Robert Thompson arranged to have played in New Orleans, identified First Progressive’s starters as Malone, McInnis and Bobby Thompson as well as two Mississippi players – Ken Gambrel (who later played at Western Kentucky) and Kolin Page (who went on to SMU).

In what now seems laughable, Dumars and Anders made up the second team’s backcourt.

“To be honest with you, I played more than I should have,” says Wenzel, who admittedly didn’t offer much beyond an ability to set hard screens and pass the ball out of the post.

Carlisle, who died in 2014, understood the ramifications of spreading minutes evenly, blaming himself for a loss to Arkansas in the Junior Nationals and telling the Times-Picayune he promised he “would play all the kids and I did.”

Anders left the team at some point after the Junior Olympics. No one can recall whether he quit or had a previous commitment. He appears to have missed First Progressive’s August trip to Provo, Utah, for the BCI Super Prep Tournament (an event different from that April’s Senior Prep). His name never showed up in local news accounts and none of the players remember him there.

Ironically, everyone’s best Utah memories were of Malone, who fell in love with the soaring mountains and wide, vivid sky. Dumars can still see him strolling the BYU campus, gazing around him and declaring: “It’s beautiful here. You know, I could live here someday.” For years, Dumars would remind him of that day, slipping it into conversations long after they had become NBA stars: “Remember how we ended that summer in Utah and then you wound up in Utah?”

For Malone and most of the other First Progressive players, the Utah games would be their last with the AAU team. School started right after they got home, their senior years were coming and they had no need for an AAU team anymore. Robert Thompson did field one last team the following spring that included Dumars and McInnis. It made the finals of the AAU junior nationals in North Carolina, but it wasn’t the same.

Soon after that the First Progressive basketball team broke apart and was gone for good.

Part VIII: ‘This Mailman is unbelievable’

One day, in the late 1980s, not long after he had been cut by the Philadelphia Eagles, Wenzel was visiting a couple of friends in New Jersey when one glanced up from a newspaper he was reading and said, “Jeff, this Mailman is unbelievable.”

Wenzel glanced around, confused.

“What’s wrong? Is your mail not coming?” he asked.

The man laughed.

“No,” he said. “Karl Malone. He plays for the Utah Jazz. They call him The Mailman because he always delivers. He went to Louisiana Tech. You’re from Louisiana, right? I thought maybe you had heard of him.”

This is how Wenzel learned that Karl Malone had made it to the NBA.

They had all split apart after that summer, so many players going different places it was hard to keep track of what happened to everyone, even those who became first-round NBA draft picks. Of the First Progressive players from those three months in 1980, only Anders and Stanfel were heavily recruited, with Anders choosing Houston and Stanfel selecting LSU before transferring to Ohio. Malone, who didn’t meet the NCAA’s freshman eligibility requirements, stayed close to home in Ruston. Coffey played at the University of New Orleans. Dumars initially committed to Florida State but had second thoughts after talking to the team’s shooting guard, Mitchell Wiggins, the father of Timberwolves star Andrew Wiggins.

“He told me: ‘You’ll be sitting for two years,’ ” Dumars says. “McNeese State [in Lake Charles, Louisiana] was like, ‘Hey, as soon as the car hits the campus, you will be starting.’”

So Dumars went to McNeese; McInnis joined him. Together they formed a backcourt for four years and a friendship for life. McInnis came home to teach at Chalmette High School, where he also coached basketball, eventually drifted into local politics, and in 2015 was elected president of St. Bernard Parish just outside New Orleans – the Louisiana equivalent of a mayor or county executive. Coffey has worked for the same parish for decades, while Stanfel became a successful financial planner in the Chicago area.

Anders was the most perplexing of them all. His moments of brilliance at Houston, including an unforgettable dunk over Charles Jones in the 1983 Final Four, was marred by frustration. Though he was probably the most talented of the First Progressive players – and maybe Houston’s as well (some suspect he could have been better than his Cougars Hall of Fame teammate Clyde Drexler) – he never could win enough playing time and eventually drifted away from basketball and family. When the “30-for-30” finally found him in Detroit, those who had known him were stunned.

“I was like, ‘He’s here? In Michigan?’ ” Dumars says.

Not long after Williams and Bobby Thompson got to Tulane, Robert Thompson was charged and convicted of mail fraud after collecting on a fraudulent loan at First Progressive. He was sentenced to three years in prison. Two years later, things fell apart for Williams and Bobby Thompson when they were implicated in a point-shaving scandal at Tulane. Williams’ arrest in the case became a big national story and his NBA career was put on hold as he twice went on trial for sports bribery. In 1986 a New Orleans jury found him not guilty and he joined the Cleveland Cavaliers that fall. He went on to play 13 years in the NBA, even becoming the league’s highest-paid player in 1990. Then in 2014 he was diagnosed with colon cancer. He died a year later.

Bobby Thompson pleaded guilty to a sports bribery charge and received a suspended sentence. After Tulane he taught high school history and coached basketball. He now lives north of New Orleans, across Lake Pontchartrain, and runs a contracting business.

Robert Thompson died in 2012. By then Dumars and Malone had long retired from the NBA and the basketball team he had founded was all but forgotten. When Bobby was at Tulane, his coach at Ganus, Larry Maples, mentioned the team to a Times-Picayune writer, saying Robert Thompson had founded it “to promote Bobby’s stock, to show people Bobby could play with those caliber players.”

Told this, McInnis shakes his head.

“If he did it for Bobby, that’s great,” he says. “But he helped a lot of other people, too. What he did for me and some of the guys was amazing. That team got us scholarships, which we wouldn’t have been able to get otherwise.”

McInnis sits now in a conference room in the St. Bernard Parish offices. It is late; he has been talking for over two hours. He wears a McNeese golf shirt, which shows off his barrel chest. Now for a moment he goes quiet. The only sound is the faint hum of traffic on the main road outside.

“You know, I wonder what Joe and Karl think,” he says. “I wonder about their perspective. Do they look at this team the same way we do? That it gave us a chance to showcase our talents?”

Halfway across the country, on a different day, Dumars ponders this question as it is asked through the phone. He pauses.

What did it mean?

“It was a whole new world,” he finally says. “Everything we were doing was new. But we found out we could play [with the best in the country]. We realized we really had a chance to make it. That summer really solidified in our minds that we are going to make it.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Woj Report: Only the Warriors stand between LeBron and Jordan

• Sources: Nuggets’ Danilo Gallinari to opt for free agency

• Summer agenda: Raptors at a crossroads

Popular video from The Vertical: