After splashy 2014 debut, Washington's 'Original Americans Foundation' zeroed out contributions

In March 2014, amid one of many protests demanding Washington’s football team change its name, team owner Daniel Snyder announced the creation of the Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation. The charity’s intent, according to Snyder, was to improve the daily lives of Native Americans in tribes across the country through a combination of gifts and educational assistance.

“For too long, the struggles of Native Americans have been ignored, unnoticed and unresolved,” Snyder said in a letter announcing the private foundation. “We commit to the tribes that we stand together with you, to help you build a brighter future for your communities. The Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation will serve as a living, breathing legacy — and an ongoing reminder — of the heritage and tradition that is the Washington Redskins.”

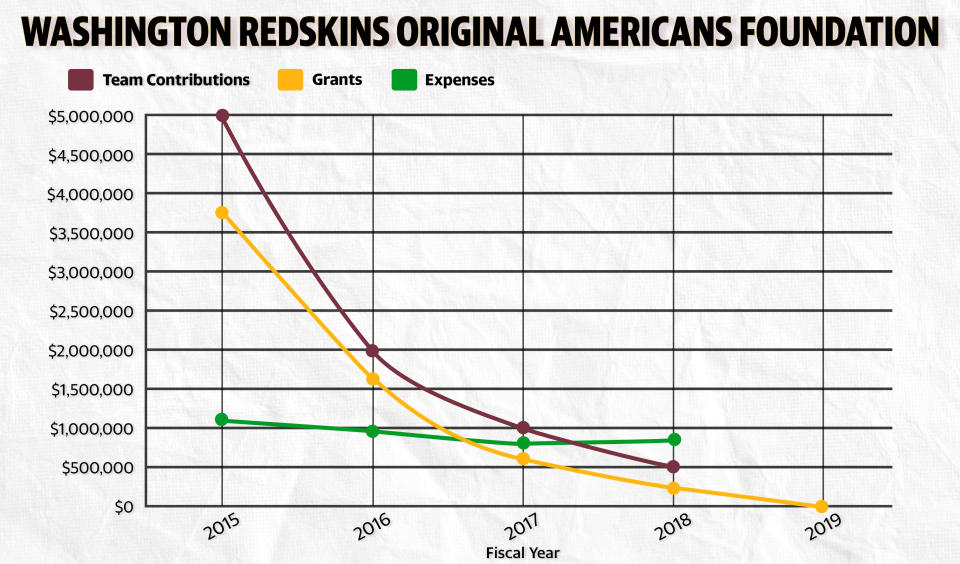

Less than four years after that announcement, the Original Americans Foundation was nearly a million dollars in the red. According to IRS filings, Washington’s contributions to the fund had declined from $5 million in fiscal 2015 to $500,000 in 2018. Even with declining contributions, salaries and operating expenses remained constant at over $750,000 per year. By fiscal 2018, grants to Native American communities had dwindled to barely 7 percent of the charity’s initial grants, and by fiscal 2019, that number had zeroed out entirely.

Washington team officials have not yet replied to Yahoo Sports’ request for comment.

Throughout the five years of existence now visible in public records, the foundation has given grants to dozens of schools and tribes across the country. But the Original Americans Foundation doesn’t even merit a mention on the team’s website, which instead focuses almost entirely on the broader-based Washington Redskins Charitable Foundation.

It’s a significant decline given how Snyder and his staff said they traveled to 26 Tribal reservations across 20 states prior to the foundation’s unveiling in 2014 to, in Snyder’s words, “listen and learn first-hand about the views, attitudes, and experiences of the Tribes.”

The Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation began in 2014 with a $5 million contribution from Pro Football Inc. Virginia records indicate Pro Football Inc. is a corporation based at Washington’s Ashburn, Virginia, headquarters. Its directors include Snyder, his mother Arlette, and two of his minority co-owners, Fred Smith and Dwight Schar.

Applicants seeking funds from the foundation had to provide only “a letter describing the need, describing the assistance that is being requested, and describing how the assistance will meet the need.”

In fiscal 2015, the foundation gave out grants totaling $3,697,000. Major recipients included the Chippewa Cree Indians of Rocky Boy’s Reservation in Montana ($685,389), the Zuni Tribe in New Mexico ($508,892), the Kickapoo Tribe of Kansas ($393,998) and the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska ($319,844). In all, 11 entities received at least $100,000 in grants from the foundation.

The foundation also recorded expenses of $1.06 million, including salaries, administrative costs and operating expenses. While Snyder was listed as a director, he did not take a salary. However, director and president Gary L. Edwards was paid $184,608.

The next three years would show a definitive trend: Washington’s contributions to the fund, and consequently grants to outside entities, declined even as costs remained relatively stable. In fiscal 2016, Washington contributed $2 million to the fund and provided grants of $1.559 million, both less than half of their fiscal 2015 totals.

In fiscal 2017, Washington contributed $1 million to the fund, and for the first time, the NFL itself kicked in $60,000. But grants dropped to $603,000, again less than half of the prior year.

Then in 2018, Washington reduced its contribution by half again, contributing $500,000 to the fund. The NFL actually increased its contribution, giving $104,000, while an entity from the Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma gave $1,000. That resulted in grants of $267,000, even as expenses topped $800,000 and Edwards drew a salary of $199,992. Only one grant, $53,157 to the Pueblo of Zuni in New Mexico, exceeded $50,000, and most grants were in the low four figures.

The high cost of salaries and operating expenses against ever-decreasing contributions meant that by the end of the 2018 fiscal year, the Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation was at a deficit of $981,000 — meaning the foundation would need nearly $1 million just to get back to zero, with none of that going to grants.

A USA Today review of the foundation’s fiscal 2019 statement found that the fund gave no money to Native American causes. Numbers aren’t available after the 2019 fiscal tax year. The charity’s fiscal year ends on Feb. 28, and the fiscal 2020 returns have not yet been made public.

Over the same period when Washington decreased its contributions from $5 million to $500,000, the revenues that the NFL distributed to each team grew from $226 million in 2014 to $255.9 million in 2017, according to The Action Network.

Moreover, the team did not fold the Original Americans Foundation’s giving into its larger charity, the Redskins Charity Foundation. In fiscal 2018, the most recent year publicly available, that foundation gave $1.25 million in grants to 21 entities, none of which were primarily dedicated to Native American causes.

Tax experts contacted by Yahoo Sports noted that there is no evidence of fraudulent activity or malfeasance in the foundation’s record of contributions, but there is a clear downward trend after the foundation’s well-covered creation several years ago.

Furthermore, the decline in donations is in itself not automatically indicative of any ulterior motive. “Sometimes you see large donations to [a private foundation] in a particular year, a few years of no donations or very small donations, then another large donation a few years later,” said Laurie Styron, executive director of CharityWatch, a charitable organization watchdog. “The timing [of donations] ... really just depends on the timing of what will provide the best tax advantage for the individual, the family or the businesses funding the PF. I would say it is actually less typical to see very steady annual donations into a PF over a span of several years.”

Styron noted that it’s not unusual for a charity to make a large initial splash and then recede after the initial wave of publicity. “I have seen a number of examples over the years of Private Foundations starting out strong, ebbing and flowing, and eventually petering out,” she said. “An athlete, actor, musician, or other celebrity in their quest to support charitable causes, whether out of genuine interest, good public relations and image, or some combination of the two, sometimes will start and actively support a private foundation for a number of years before gradually losing interest and letting it peter out.”

Over the course of the foundation’s operation, the grants themselves became controversial. Members of the Chippewa Cree Tribe in Montana noted that they understood the rationale behind the grants, but weighed the benefits to the tribe against taking a stand opposing the name. Washington built a burgundy-and-gold playground on the tribe’s land.

"If us accepting the money makes [team officials] sleep better at night, then fine, I wish them a good night's sleep," the tribe’s Mike Sangrey said in 2014. "What matters is our kids get to enjoy a new playground. And how can that be bad?"

However, several communities turned down the team’s offer of funding, viewing it as tantamount to endorsing the team’s name.

Members of the Fort Yuma Quechan Tribe in Phoenix declined the team’s 2014 blank check to build a skate park. “We will not align ourselves with an organization to simply become a statistic in their fight for name acceptance in Native communities,” the tribe said in a statement. “We're stronger than that, and we know bribe money when we see it."

______

Jay Busbee is a writer for Yahoo Sports. Follow him on Twitter at @jaybusbee and contact him with story ideas and tips at jay.busbee@yahoo.com.

More from Yahoo Sports: