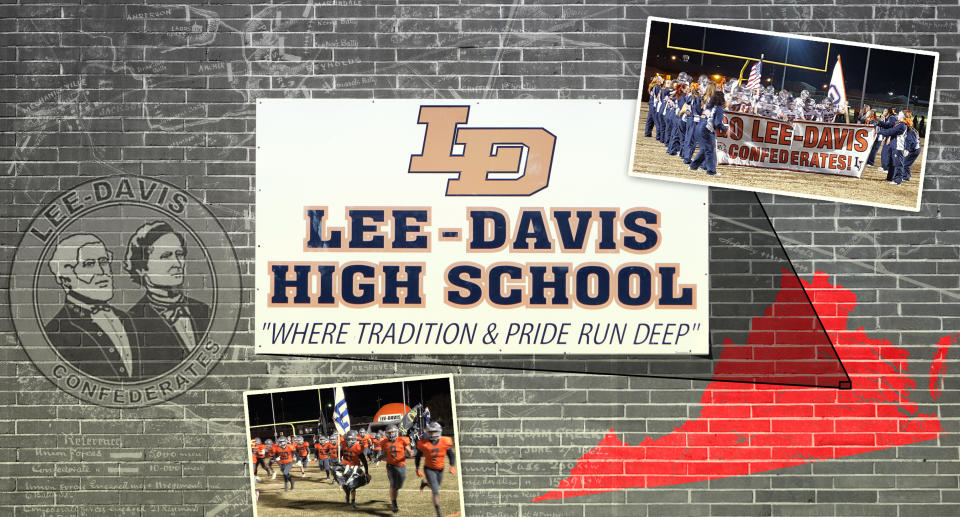

Go Confederates? A town divided over its high school and its mascot

After 16 years, the words remain emblazoned in Samara Hulin’s memory.

“Go, go Confederates! Hey, go Confederates!”

It’s the chant that made her uncomfortable to try out for the cheerleading team at her suburban Virginia high school. It’s also the chant that she slyly refused to say correctly after she finally did join.

Hulin grew up outside Richmond in a predominately white town steeped in Civil War history. Not only was her high school named after Confederate leaders Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, it is also one of just four nationwide whose mascot is still the Confederates.

For Hulin, Lee-Davis High’s divisive name turned cheerleading into an ethical dilemma. She had to assess if she loved the sport enough to stomach cheering for a mascot that represented the oppressors of her African American ancestors.

When Hulin did become Lee-Davis High’s lone Black cheerleader from 2002 to 2004, she joined the team on her terms. She staged a secret protest anytime the team performed certain chants during competitions or football games, covertly replacing “Confederates” with whatever other C-word popped into her mind.

Sometimes it was Go, go Cupcakes! Or Go, go Coffee! Or, if she was feeling particularly cheeky, Go, go Crackers!

“It was kind of like my own little inside joke, my own little silent protest so that I could get through the cheer,” Hulin told Yahoo Sports. “No one could hear what I was saying because the crowd was cheering and the girls were cheering. They probably assumed we were all saying the same thing.”

Hulin’s private struggle over that pro-Confederate chant exemplifies why an outspoken group of students, alumni and community members have been calling for change in Hanover County. They have petitioned the Hanover County School Board to rename not only Lee-Davis but also neighboring Stonewall Jackson Middle School, whose mascot is the Rebels.

The crux of their argument is that public schools who pay homage to the Confederacy aren’t fulfilling their obligation to treat all students equally. Confederate symbols alienate minorities and convey a preference for whites.

Protests over racial inequality have spurred a nationwide reckoning over Confederate imagery in the public sphere the past few years, but the fight to rename the two Mechanicsville public schools has been particularly contentious.

This is a community where quiet residential neighborhoods back up to Civil War battlefields and cemeteries, where neo-Confederate groups march in the annual Christmas parade and hand out flags to revelers. There are longtime residents who are direct descendants of Confederate soldiers and have a hard time seeing why others don’t share their romanticized view of the South’s cause.

“There are Blacks that have gone to Lee-Davis High School and gotten a great education or gone on to play pro sports,” Arthur Smith, a 1970 Lee-Davis graduate and lifelong Hanover County resident, told Yahoo Sports. “Nobody has been able to tell me how the names are hurting the Black community’s education. I just wish one time they would come out and say how it’s hurting them.”

Integrating Lee-Davis High School

The night before he and five other Black students integrated Lee-Davis High School in 1963, Walter Lee knelt beside his bed and prayed for his safety.

“I felt like I was going into the lion’s den,” Lee told Yahoo Sports. “I knew I wasn’t going to be well-liked because of the color of my skin.”

Lee-Davis opened four years earlier as an all-white high school. The Supreme Court ruled that all public schools had to desegregate in 1955. Virginia was among the Southern states that resisted for years, using legal and political means to prevent enforcement of that decision.

Historians suspect Hanover County's 1958 decision to name its new school Lee-Davis may have been as much about deterring prospective Black students as honoring two prominent members of the Confederacy. The selection of the name coincided with a spike in Confederate-themed school names, symbols and monuments across the South during the modern civil rights movement.

A 2019 study by the Southern Poverty Law Center found 103 public schools and three colleges named after Lee, Davis or other Confederate icons. Thirty-four were built or dedicated from 1950 to 1970, an upsurge that historians say wasn't coincidental.

“I do think the naming of the schools was partially directed at preserving segregation,” said VCU history professor Brian Daugherity, whose research focuses on Virginia’s resistance to Brown v. Board of Education. “That’s not something that’s easily proven. It’s probably not something that could ever be proven. But I think that recognizing the time period and what was happening, the adoption of those names was part of the resistance strategy. It was a way of telling Blacks that they were not welcome.”

The alleged scare tactics didn’t deter Walter Lee when the NAACP approached his parents during the summer of 1963 and asked if he and his brother would help integrate Lee-Davis. Hanover County’s lone Black high school was 30 miles from Lee’s home, but he could bus to and from Lee-Davis in just a few minutes.

When Lee came to Lee-Davis that fall to begin his sophomore year, he remembers “a lot of whispers, a lot of stares and a lot of looks.” He and the school’s five other Black newcomers required a police escort to enter and exit school and to get to classes safely.

Asked if things got easier after a few weeks, Lee responded sharply, “God, no.” He said he was a target of spitballs in his classes and cruel jokes in the halls all the way up until he became the school’s first African American graduate in 1966.

Of course, it wasn’t just the icy reception from their peers that made Lee-Davis High’s first African American students feel like outsiders. The school reinforced that with class rings engraved with the Confederate flag and the likenesses of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. Or by playing “Dixie” and other rallying songs of the Confederacy during pep rallies.

“All the students would stand and clap their hands to the rhythm and I could only sit there and watch in horror,” Nannie Davis, a 1967 Lee-Davis graduate, told the Hanover County School Board in December 2017. “To top it off, there was one student who would always do the rebel yell and parade around the floor with a large Confederate flag. It was so humiliating.”

School pride?

It’s easy for some of Lee-Davis High’s most decorated athletes to identify with the shame those pep rallies brought Nannie Davis. They felt similar embarrassment every time they looked at the name emblazoned on the front of their jerseys.

Avi Hopkins rushed for over 4,000 yards for Lee-Davis in the early 1990s and earned all-state honors on the wrestling mat, but he views those athletic accomplishments with mixed emotions. The great-great grandson of a slave questioned the morality of representing a school named after men who fought to keep his ancestors in shackles.

“I tried to push it out of my mind because I loved playing so much,” Hopkins told Yahoo Sports, “but in my latter years of high school there were times when I didn’t want to participate.”

One of the leading goal scorers in Lee-Davis boy’s soccer history regrets not sitting out games in protest of his school’s name and mascot. Eduardo Lopez dreaded being introduced before games as a Lee-Davis Confederate from 2006-2009 or fielding questions from athletes of color on the opposing team about his school’s name.

“There was no pride for me in representing the Lee-Davis Confederates,” Lopez told Yahoo Sports. “It was awkward. It was embarrassing. I only played because I loved the sport.”

Former triple-jump and hurdles state champion Montasia Golden never questioned Lee-Davis High’s name and mascot until she told her roommates about them during her freshman year at Wake Forest. To this day, the horrified looks on her roommates’ faces are burnt into Golden’s memory.

“That’s the moment when I realized that it wasn’t OK,” Golden told Yahoo Sports. “The reason the people in our town have such strong ties to these names is that they’re only around people with opinions and feelings like their own. If they stepped out of their comfort zones and learned how other people see the world, they would realize very quickly that other people think this is absolutely terrible.”

Not all students of color are willing to represent one of Hanover County’s two schools with a pro-Confederacy name. Some have chosen not to participate in sports, sought permission to attend other Hanover County schools or resorted to even more drastic measures.

An African American military veteran, his West-Indian wife and their two boys reside in a part of Hanover County zoned to Stonewall Jackson and Lee-Davis. The parents opted to home-school their eldest son when he began sixth grade after Hanover Public Schools denied their request to send him to another middle school in the county.

“For us, Stonewall Jackson was not an option,” said the mother, who requested anonymity since Hanover Public Schools is currently reviewing her variance request for her younger son. “We didn’t want to leave our son with the impression that it was acceptable for him to be viewed as less than equal.”

‘Perfuming a pig’

It’s clear that Lee-Davis administrators have tried to make the school more welcoming to students of color. The amount of Confederate imagery on campus has gradually declined.

Among the first casualties was the Confederate soldier mascot. Lee-Davis had someone dress in a bulldog costume in the late 90s and 2000s before abolishing mascots altogether.

The use of the word “Confederates” on the school’s athletic jerseys is now a relic too. For years, the school has instead favored an interlocking LD logo, “Lee-Davis” or “LDHS”.

Cheerleaders have also long been encouraged to tread lightly. They’re more likely to chant for LDHS or the C-Feds now than the Confederates.

Those offended by Lee-Davis High’s name and mascot appreciate the spirit of those changes but liken them to perfuming a pig. Lee-Davis High School is still home of the Confederates. Images of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis still adorn the walls of the gym and the bleachers at the football stadium. The school’s yearbook is still called The Confederate.

“It’s a Band-Aid,” Golden said. “It’s not just the Confederates. Our name is Lee-Davis. We know who those people are and we know what those people fought for. Why would we ever want to be on that side of history?”

African American critics of Lee-Davis High’s name argue its longevity is symptomatic of racial bias within the Mechanicsville community. As proof, they share tales of finding KKK flyers on their windshields, receiving disapproving stares for dating outside their race or being tailed by police for miles for no apparent reason but their skin color.

For years, “redneck row” was what students dubbed a section of the Lee-Davis parking lot lined with lifted trucks displaying Confederate flags and emblems. It was common to see Confederate flag T-shirts on campus, some bearing the slogan, “If this shirt offends you, you need a history lesson.”

Former Lee-Davis principal Stan Jones once caught a few students flying the Confederate flag at a football game against Armstrong High, a predominately Black school. The students’ intent was clear to Jones, so he told them the brave thing to do would be to take their flag to inner-city Richmond and fly it in front of Armstrong’s campus.

“I don’t think they took my advice on that,” Jones told Yahoo Sports with a wry chuckle. “It was interesting to me that all of a sudden when we were playing Armstrong, they wanted to fly the flag. That was not our first game that season.”

A town divided

Only a few days after watching a 2017 Charlottesville far-right rally turn deadly when a white nationalist rammed his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, Ryan Leach decided this was the time to take a stand.

The 2010 Lee-Davis graduate and New York resident posted to Facebook urging his alma mater to disassociate with the Confederate names, symbols and imagery used by extremist groups.

“Please let me know if any LDHS alumni would be interested in a local, state or national campaign to FINALLY change the name and mascot of Lee-Davis High School,” Leach wrote.

Leach’s 700-word post shined a spotlight on many of the issues concerned Lee-Davis students had been discussing for years. He recalled the discomfort of hearing the cheerleaders chant “Go Confederates, go” at football games, of spotting Confederate flags on public school property and of seeing banners with the slogan “Tradition & Pride” accompanying images of Davis and Lee.

Hundreds of students, alumni and teachers signed Leach’s online petition calling for Lee-Davis and Stonewall Jackson to change their names and mascots. Hundreds more were vehemently critical of Leach’s stance.

“I was called a f-----,” Leach told Yahoo Sports. “I was threatened. I was told that I wasn’t from here or that I forgot where I came from. People were saying that I was stirring up trouble.”

On Dec. 12, 2017, eight proponents of change spoke to the Hanover County School Board and 2010 Lee-Davis graduate Amanda Lineberry presented Leach’s petition. That served as a clear warning sign to the rest of the community that the names were under attack.

By the next school board meeting on Jan. 9, 2018, a petition to keep the names started by 1977 Lee-Davis graduate Marsha Boyce Rider had over 7,000 signatures. That was nearly four times as many as Leach’s petition had at the time.

“These numbers should speak volumes,” Boyce Rider told the school board. The lifelong Hanover County resident and mother of a Lee-Davis student went on to portray the pro-change movement as a “witch hunt” run by outsiders.

In a passionate defense of Lee-Davis High, Boyce-Rider cited the school’s excellent academic reputation, widespread campus pride and successful track record in sports. She added that in three years of volunteering with Lee-Davis athletics, she had never heard one student say, “I’m ashamed to play for Lee-Davis High School.”

Wade Hughes, a 1969 Lee-Davis graduate who went on to play running back at Clemson, also spoke that night. In addition to pointing out that it could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to change the names of two schools, he also cautioned against condemning Confederate leaders for fighting for the pro-slavery side of the Civil War.

“The Civil War was not fought over just slavery,” he said. “It was not the most important issue for the Southern states. Many more issues were ahead of this.”

Arthur Smith, the 1970 graduate, is the great grandson of a Confederate solider who Smith says was not fighting for the preservation of slavery.

"My great-grandfather fought in the Civil War right here in Hanover County,” Smith explained. “He was not fighting for slavery. He was fighting to protect his family, his home, his crops, his livestock, his livelihood. That’s why he fought in the Civil War. So don’t label him as pro-slavery just because he was fighting for the South.

“My ancestors watched their barns being burnt, their cattle being slaughtered, their crops being destroyed by the union army. They had no choice but to fight."

Having heard arguments from both sides, Hanover County School Board chair Sue Dibble asked superintendent Michael Gill to create a survey tool that would help gauge public opinion within the community. Dibble hinted that the results of the survey would dictate the board’s decision, saying at the meeting that this was a “local matter” and that the board was “a direct reflection of the community we serve.”

Of the more than 13,000 Hanover County residents who responded to the survey, a little over 3 in 4 wanted to keep the Lee-Davis and Stonewall Jackson names and mascots. Eighty-five percent of alumni of both schools were on that side of the argument, as were 83 percent of parents of students at the two schools.

On April 10, 2018, in front of a standing-room-only crowd that applauded the decision, the school board voted 5-2 to keep the school names undisturbed. The vote extinguished hope of immediate change. It wouldn’t be long before the school board had to address the issue again.

Awaiting a decision

Last August, on the heels of a KKK recruitment drive near the Hanover County courthouse, the NAACP filed a lawsuit arguing that the names of Lee-Davis and Stonewall Jackson violate the constitutional rights of African American students. A federal judge dismissed that lawsuit in March, arguing that some claims were too broad and that the window for alleging damages had closed on others.

The outcome of an NAACP appeal may not matter given how America has changed over the past few months. The deaths of George Floyd and others have made the county more sensitive to racial injustice than ever before, reigniting the debate over the merits of statues, monuments and street and school names honoring Confederate icons.

On June 19, hundreds of Black Lives Matter protesters braved a powerful rainstorm to march in Mechanicsville and call for the renaming of Lee-Davis and Stonewall Jackson. Almost 25,000 people have signed a second online petition to change the names of the schools, this one created last month by Lee-Davis student Sophie Lynn.

Concern over the momentum for change inspired a leader of the Virginia Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans to write a June 22 letter to the Hanover County School Board. Andrew Morehead implored the board “not to bow to the whims of what is truly an unjust movement [led] by violence and pure evil from outside this community.”

“To change the names of these schools and mascots would be in stark contrast to the will of the majority of Hanover residents,” Morehead wrote. “What statement would that make for ‘educating’ youths of the world?”

The school board abruptly adjourned its June 23 meeting without a vote after meeting behind closed doors for two hours to discuss the renaming decision. That delayed an expected decision on the matter until at least July 14.

It’s the hope of advocates for change that the board now recognizes it has a duty to provide equal rights to marginalized students rather than siding with the majority in a community that is roughly 80 percent white.

To Hulin, that means never again asking another African American cheerleader to chant for a mascot that represents the fight to preserve slavery.

“It’s disheartening to be a black kid at a school whose mascot is the Confederates,” Hulin said. “It kind of says we do not care about you, your history or your feelings. It’s really sad. We’re not in the 1800s anymore. I am happy that change is coming.”

More from Yahoo Sports: