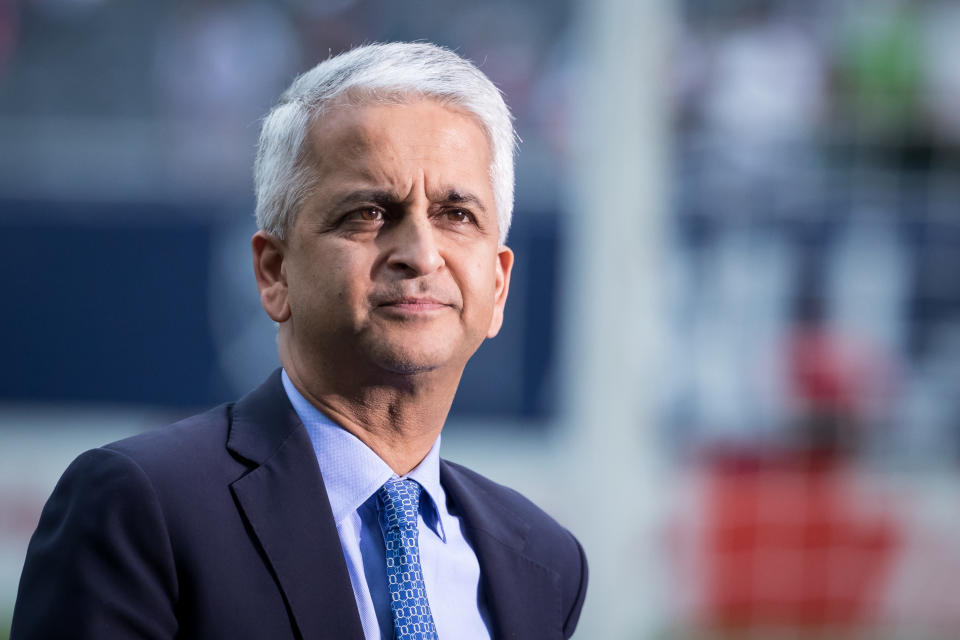

As 2026 World Cup bid approaches, Gulati isn't done with soccer, and soccer isn't done with him

NEW YORK – Sunil Gulati can’t help himself. He’s been asked to give a talk titled “Ethics, Values and Sports – Some Case Studies” for a group of international journalists who have come to the journalism school at Columbia University, where Gulati is an economics lecturer, for a seminar. And he’ll get to all that soon enough, speaking candidly for two and a half hours about his many conflicting and ethically treacherous experiences – all off the record, sorry – as president of U.S. Soccer and as a longtime bigwig within FIFA and CONCACAF, the global and regional governing bodies, respectively.

Before he gets started in a large, bright room that’s nevertheless imbued with that unmistakable Ivy League mustiness, Gulati hands out World Cup bid swag to eager recipients. And that’s how he learns that one of the journalists is from Morocco: She makes a joke.

It’s just over a week before the FIFA Congress will decide whether the 2026 World Cup will go to a joint-bid made up of the United States, Mexico and Canada, or to Morocco. And so it’s just over a week until Gulati will find out if years of toil and brokering within soccer’s long and shadowy corridors of power will have paid off.

He rejects the notion out of hand, but four months on from his sudden departure as president of the United States Soccer Federation, this decision will also frame Gulati’s legacy.

To many, he will either be the man who played a major role in bringing two men’s and two women’s World Cups stateside but didn’t always get the big coaching appointments right, or the man who enabled the fateful Jurgen Klinsmann era and failed to deliver both the 2022 and 2026 World Cups. And all that will hinge on FIFA’s vote on Wednesday, June 13.

[2026 World Cup bid primer: All you need to know about the vote]

Is that fair? Probably not. But then administrative careers spanning several eras and encapsulating countless decisions both pivotal and granular tend to be judged by a handful of calls.

But now, two days before he leaves for Russia, Gulati has found a target for his acerbic wit. He says something to the effect that Morocco will enjoy a wonderful 2026 World Cup, if only it travels to North America to come and see it.

Gulati wasn’t in charge of the homestretch of the bid. In February, U.S. Soccer’s intricate network of members and voters picked his longtime right-hand man Carlos Cordeiro to succeed him. And while Gulati was still on the board of directors of the bid, Cordeiro, along with the heads of the Canadian and Mexican federations, took the reins in March. Which must make this a strange moment for Gulati.

Because he was very much the driving force behind this bid, as he was for the 2022 bid, which was lost to Qatar in high controversy and, we can safely say, rampant corruption. In his decades in the sport, Gulati patiently climb the ranks at U.S. Soccer and then at CONCACAF and FIFA.

And then he became a kingmaker as one of the few men left standing after a series of raids, arrests and indictments washed through FIFA’s boardroom. Years of careful political maneuvering paid off as Gulati swung a major voting bloc toward Gianni Infantino in the FIFA presidential election after Sepp Blatter finally stepped down. That’s a sizable IOU to hold in your back pocket.

So just as he had in 2010, when the 2018 and 2022 World Cups were awarded simultaneously, Gulati engineered the bid. The U.S. was the favorite and stunned by the upstart Qatar then. But Gulati is confident this time around. It’s looking like all of the Americas are committed to the U.S.-Mexico-Canada bid, while much of Africa will support Morocco. Europe and Asia are in play, but enough of those regions should declare for North America to ensure a comfortable victory.

“I think things are in quite good shape right now,” Gulati tells Yahoo Sports. “But until a vote happens and you’ve worked until the last moment, you never know.”

He’d learned a lot from the last go-around. Gulati had made it very clear to his FIFA brethren that the U.S. – which could guarantee more revenue than any other host and offer a rare absence of risk – wouldn’t bid again unless wholesale changes were enacted. This time, there aren’t 22 voters but more than 200, from every member federation whose votes will be public. There are only two bidders. And the technical report, which heavily favors the North American bid over Morocco – because whereas the U.S., Canada and Mexico wouldn’t have to build a single new stadium, Morocco has to build all of them – actually matters.

So Gulati spearheaded another effort. And in that sense, it all feels the same as the last time, almost eight years ago. His entire life, in fact, is more or less the same. He still has the famously soft handshake and walks so fast you can hardly keep up with him. He still works out of the same 10th-floor office, its walls covered in soccer mementos.

He and his family still live in the same unremarkable apartment provided to Columbia faculty on the Upper West Side that they have for the last 15 years. He still isn’t terribly interested in food or clothes. His son Emilio, now a political science major at Columbia who will be a junior in the fall, still tags along to soccer events. And Gulati still doesn’t appear to have any hobbies outside of soccer, which consumes his life as he still sits on the U.S. Soccer board, the CONCACAF Council and the FIFA Council.

But two things have changed. He bought a car recently, which he hadn’t owned for a long time, and he is no longer running U.S. Soccer, the organization to which he gave so much for 32 years.

“There aren’t many countries in the world that can show (the United States’) level of progress or success in a quarter of a century.”

– Sunil Gulati

After a dozen years as U.S. Soccer president, six as vice president and another decade as what Gulati describes as “de-facto secretary-of-state,” he decided not to run for a fourth and final term. (He was grandfathered in from the old system, allowing him one term past the recently instituted three-term limit.)

Gulati was involved in launching a successful professional men’s league and then a second tier and was crucial in getting a new women’s league off the ground after the prior two failed. And during his tenure, all manner of other advancements were made, like full-time referees and a vastly expanded youth national team program. The women’s team won three World Cups while the men qualified for seven straight, reaching the knockout stages in three of the last four – which only six other countries can boast. And the United States might yet host four World Cups in just over three decades.

“There aren’t many countries in the world that can show that level of progress or success in a quarter of a century,” Gulati says.

But then Trinidad happened, with the Americans concluding a shambolic qualifying campaign – with the first mid-cycle coaching switch since the 1980s – with an upset loss to the Soca Warriors last October. A fluky confluence with other results meant the Yanks would be staying home for the first time since 1986.

“After the loss in Trinidad, there was obviously a lot of thinking about it,” Gulati recalls. “And I decided a month later that it would be best to have a change, both for me and for the federation. It wasn’t the gameplan. I’d be lying if I said that was the gameplan.”

Gulati had figured that if the U.S. qualified and the 2026 bid was successful, he could have been part of 10 straight men’s World Cup qualifications. That was his goal.

But the backlash to the failure to reach Russia this summer was so overwhelming that Gulati reconsidered.

“Clearly, there was a lot of negative reaction not qualifying, and you have to accept, some, most, or all of the responsibility for us not qualifying,” he says. “I wasn’t going to resign. When you’re an elected official in an organization like this, we have an orderly process and we were a few months away from an election, so that was the way to go about it.”

He talked to some people he was close to and was assured that he still had broad support with the voters, who tend to be soccer administrators up and down the pyramid. It’s extremely likely that if Gulati had decided to run again, he would have won another term in a landslide, in spite of Trinidad. “I think there would have been a fair amount of support,” he acknowledges.

“More people care … they have a way of making their views known – social media. Everyone has a megaphone.”

– Gulati

But he also concedes that the outcry among the fan base swayed him to leave, even if the sport’s establishment stood by him.

“More people care,” Gulati says. “They’re more knowledgeable. They’re more passionate. And they have a way of making their views known – social media. Everyone has a megaphone.”

Now, he’s less worried about looking back than making the most out of potentially another stateside World Cup.

“It’s not about the 32 days of the event,” Gulati says. Because neither the U.S., nor its neighbors would have to build any significant infrastructure, leaving a lot of bargaining chips on the table with would-be host cities. It leaves money for other things. Lasting things. Things that can remake the American soccer landscape as much as all the attention brought by the 1994 edition.

Gulati insisted on submitting more candidate cities to FIFA than was customary or preferred by the governing body. Because that way he could barter for grassroots soccer investment.

“We want to be able to talk to cities and say, ‘Hey, you don’t have to build anything here, but let’s have an after-school program,’” Gulati says.

If the bid is successful, the cities hoping to host – there are 17 remaining in the U.S., which would host 60 of 80 games, after another 17 cities were either eliminated or dropped out – will compete by demonstrating their commitment to soccer at every level. How many season tickets does its NWSL team sell? How many fields have been built in the inner-cities lately? Is soccer part of the public school curriculum? That sort of thing.

“It’s building a soccer infrastructure,” Gulati says. “Not a building infrastructure.”

The prospect clearly excites him. And it seems to supersede any regrets he might have about how things turned out in his U.S. Soccer presidency. He tries not to linger on it. “There’s so many things you’d want to redo if you had the benefit of hindsight,” he says.

As president, he was known most of all for his steady and measured approach. His view forever fixed on the long-term.

“That’s one of the things I regret,” Gulati admits. “I wish I’d pushed harder on certain things I wanted to see us do – do them earlier.” Pressed for specifics, he settles on “diversity” in both the national team player pools and the larger U.S. Soccer organization.

On the biggest charge against him, hiring the inconsistent Jurgen Klinsmann as his men’s head coach and then sticking with him for five and a half years as results and the team disintegrated, Gulati is more sanguine. Once he fired Klinsmann in late 2016, it was too late for Bruce Arena to rescue the qualifying campaign. Klinsmann, for his part, maintains that the U.S. would have qualified if he’d been allowed to see out the job.

“Did we wait too long?” Gulati asks. “You know, listen, any time you’re not successful at something – and in this case we weren’t successful at qualifying – when you look back, you certainly reevaluate and say, ‘Yeah, I would do some things differently.’ And the answer is true here.”

As often, he won’t be more specific. “[When we hired Klinsmann] we never expected, all of a sudden the following week, to be playing like Spain,” Gulati says. “You need the right players, in the end. And we weren’t going to change the players overnight.

“Jurgen brought a lot of good qualities that we thought would be helpful to the program and in many cases were. Some didn’t go as well as we would have liked. Some were attributed to him and shouldn’t be – negative and positive. And some others should have been attributed to him – negative and positive.”

Younger fans might remember Gulati as the president who let Klinsmann run amok. And if the 2026 World Cup is played in Morocco, that will probably be a large part of his legacy. And that probably won’t be fair, considering the broader sweep of all that Gulati has done.

He certainly doesn’t seem to think so. “I don’t look at my term as 12 years,” he says. “I look at my involvement in the game as a 30-year period. I look at all of that and what the game has accomplished and where the game has gone. I got involved with the national team program in 1986. Most of the young fans weren’t alive then. They don’t know where we were in 1986. And even if they’re 45, they’re not likely to have worried too much about where we were then.”

But then Gulati doesn’t spend a great deal of time worrying about any of this anyway. He’s delved into it for this article because he was prompted and pressed several times. This kind of contemplation is for men who have approached the end of whatever it is they’re doing. And that’s not where Gulati sees himself.

“To be honest,” he says, “I don’t think about legacy issues very often, because I’m still very much involved in the game. And so you start thinking about those later on. I don’t think about these last 12 years as the only part of it and I don’t look at it as being over at this point.”

Leander Schaerlaeckens is a Yahoo Sports soccer columnist and a sports communication lecturer at Marist College. Follow him on Twitter @LeanderAlphabet.

More soccer from Yahoo Sports:

• 2018 World Cup preview hub

• Everything you need to know about the 2026 vote and bid

• 2018 World Cup contenders, tiered and ranked 1-32

• Carlos Cordeiro’s first 100 days