Redlining has a lingering effect on black homeownership: study

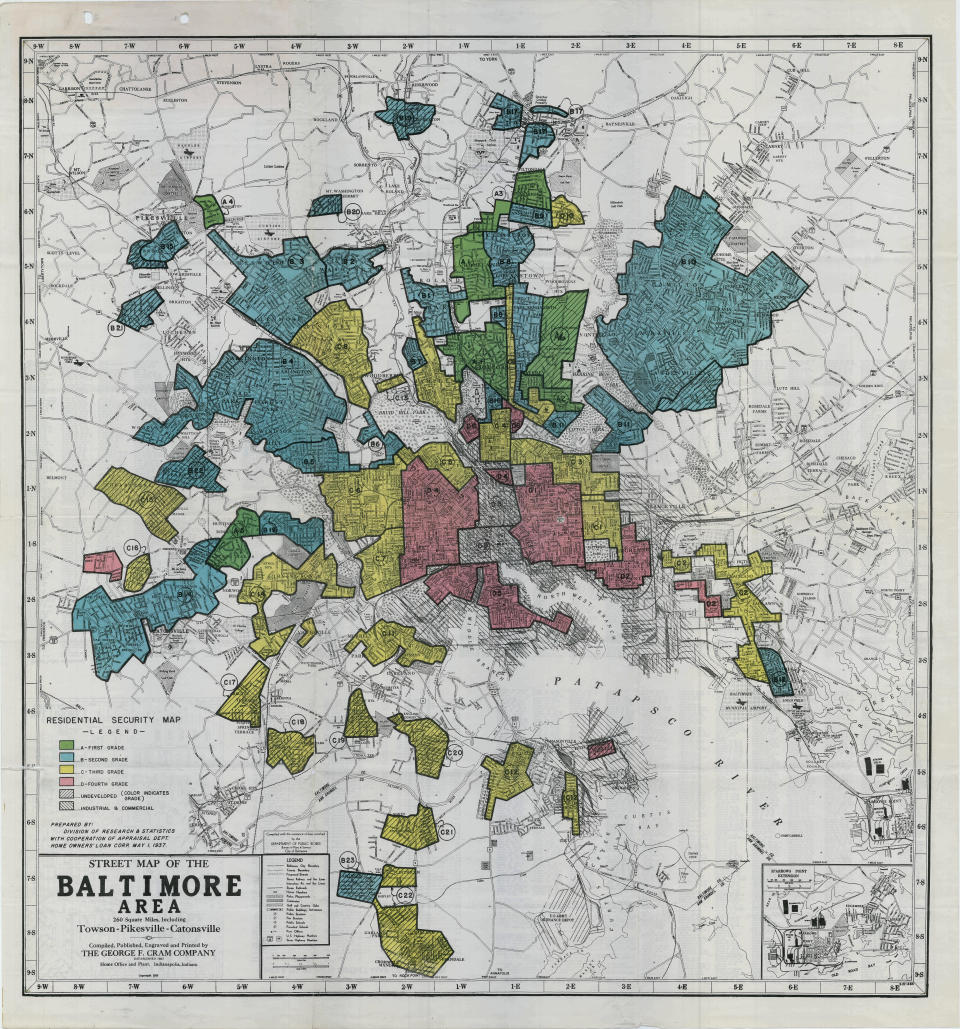

Before 1968, mortgage lenders used racially-charged language to assess whole neighborhoods for creditworthiness. They then color-coded neighborhoods, which were legally segregated, to determine which residents would be eligible for mortgage loans.

Greenlined areas received the best credit ratings and the easiest access to loans. While redlined neighborhoods, which had mostly black residents, were deemed “hazardous” credit areas, making homeownership for people who lived in redlined areas almost impossible. Statistics show that other minority groups also faced lending discrimination, but black Americans were particularly negatively impacted by the redlining policy, Redfin found.

The U.S. may have outlawed redlining more than 50 years ago as a discriminatory policy, but homeowners in formerly redlined areas are still losing money from the racist mortgage lending policy, a new Redfin study shows.

“Redlining policies kept black Americans from homeownership, and that created more segregation in the country, which has been difficult to break and rebuild from. It has been a difficult process of catchup for black Americans,” said Redfin senior economist Sheharyar Bokhari, who authored the study.

Home prices in formerly redlined areas are still catching up. Prices in redlined areas rose 292% since 1975 compared to only 204% growth in greenlined areas. But even with the rapid pace of growth, formerly redlined areas have not yet caught up. Homeowners in these areas make much less money on their home investment — about $212,023 less on average — than those in formerly greenlined areas, the Redfin study showed.

A cycle of poverty has led to fewer amenities in formerly redlined areas; Grocery stores, competitive schools and shopping centers would boost property values, said Bokhari. Plus, renovation and beautification add to home values but is much more likely when homes are owner-occupied. Landlords allowed redlined areas to fall into disrepair, depressing home values, said Bokhari.

But most residents in formerly redlined neighborhoods don’t have to worry about home prices: Only 38.5% are homeowners, compared to 66% homeownership in greenlined areas. The disparity is apparent regardless of race. Only 45.6% of white families in redlined areas are homeowners, compared to 71% in greenlined areas, and only 29.8% of black families own in redlined areas compared to 44% in greenlined neighborhoods, according to Redfin.

Since most residents in formerly redlined areas tend to be renters, already difficult financial situations are compounded — families are paying rent instead of building wealth through homeownership.

“Homeownership is one of the keys to socioeconomic mobility. That’s not just dependent on whether home prices go up, it’s the stability of homeownership — knowing that rent is not going to go up, so families can plan, save and grow capital,” said Vishal Garg, founder of Better.com, an online mortgage lender.

Echoes of the redlining policy disparately impact black Americans. Despite the end of legal segregation, black Americans are still 4.7 times more likely to own a house in a formerly redlined neighborhood than in a greenlined neighborhood, Redfin found.

While not solely due to redlining, homeownership is still low among black Americans. Nationwide, only 44% of black Americans owned a home, compared to 73.7% for non-Hispanic whites in the first quarter of 2020, according to ComplianceTech, a Virginia-based analytics company.

Discrimination in mortgage lending

Today, it is still harder for black Americans to get a mortgage than it is for whites. Some 30% of black mortgage applicants are rejected compared to 15% of white applicants, according to ComplianceTech.

“Credit history is one of the most important reasons why those mortgages are rejected for black Americans. Why is that? The financial crisis hit black homeowners a lot harder and ruined their credit history. It is still affecting their ability to buy a home,” said Bokhari.

The 2008 financial crisis exacerbated racial disparity when 7.9% of black homeowners suffered foreclosure, compared to 4.5% of white homeowners, and black homeownership dropped from 50% to 44%, Redfin found.

But discrimination may also play a role. Minority applicants have higher approval rates when they don’t have to interact with lenders in person, though discrimination can also be embedded into approval algorithms for online lenders, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, a Massachusetts-based research nonprofit.

“I don’t think that they [lenders] can” be more inclusive in their mortgage lending without revamping lending operations, said Garg. “They need to hire different people to speak to America's base of future homeowners. It is a generational and operational challenge for banks in this country.”

Sarah Paynter is a reporter at Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @sarahapaynter

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.

Read more on redlining:

Google's new rules clamp down on discriminatory housing, job ads

'Educational Redlining': New report alleges discrimination against certain student loan borrowers

Facebook comes under fire for housing discrimination and redlining