5 failures of the 2010s

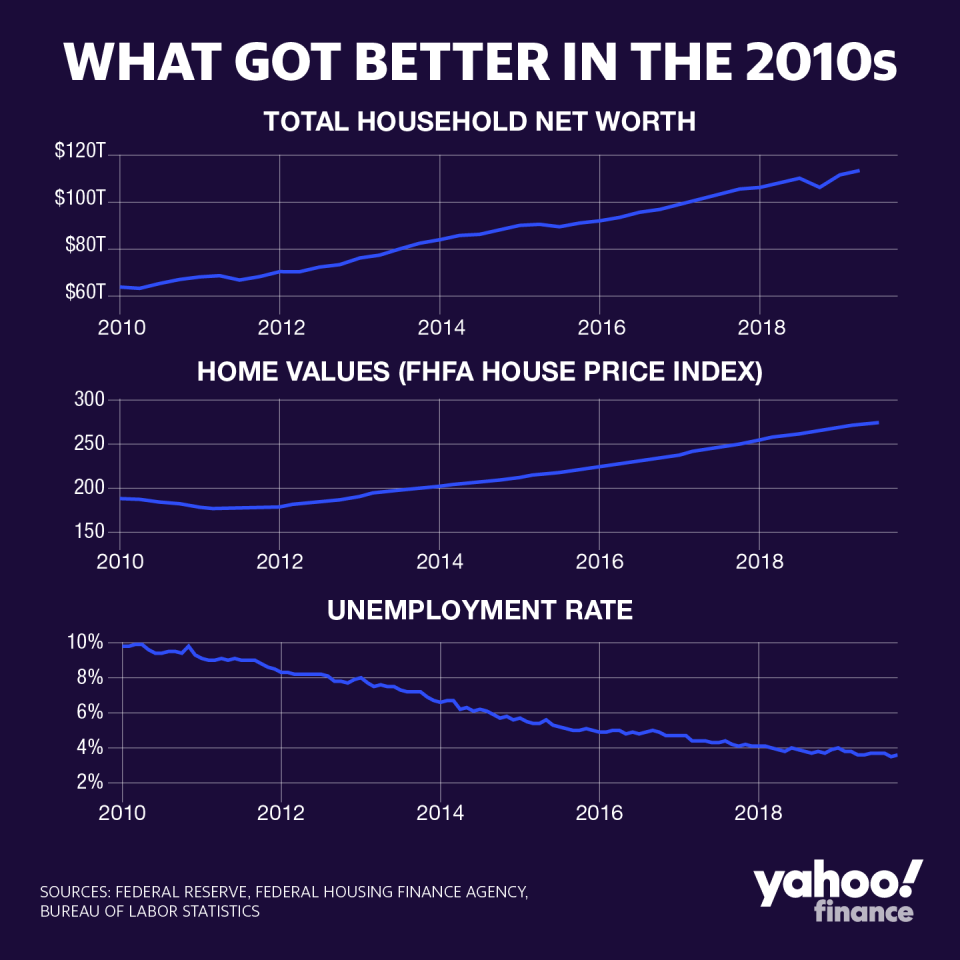

We’re far better off today than we were a decade ago. On Jan. 1, 2010, a grueling recession had just ended, but the unemployment rate was still 9.8%. Fifteen million Americans were out of work, more than twice the number of two years earlier. Nearly 2 million families would lose their homes to foreclosures that year, the most ever.

As the 2010s wind down, the economy seems like it’s back to normal. Unemployment has plunged to 3.6%, the lowest in 50 years. Since a 7-year housing bust ended in 2013, home values have risen 57%. And a bull market in stocks that began in 2009 still continues, with the S&P 500 up a rousing 180% during the last 10 years.

But those soothing figures mask new or deepening fissures in the U.S. economy. And problems that took root in the last decade could come to plague the next one. Here are the 5 most troubling economic developments of the last 10 years:

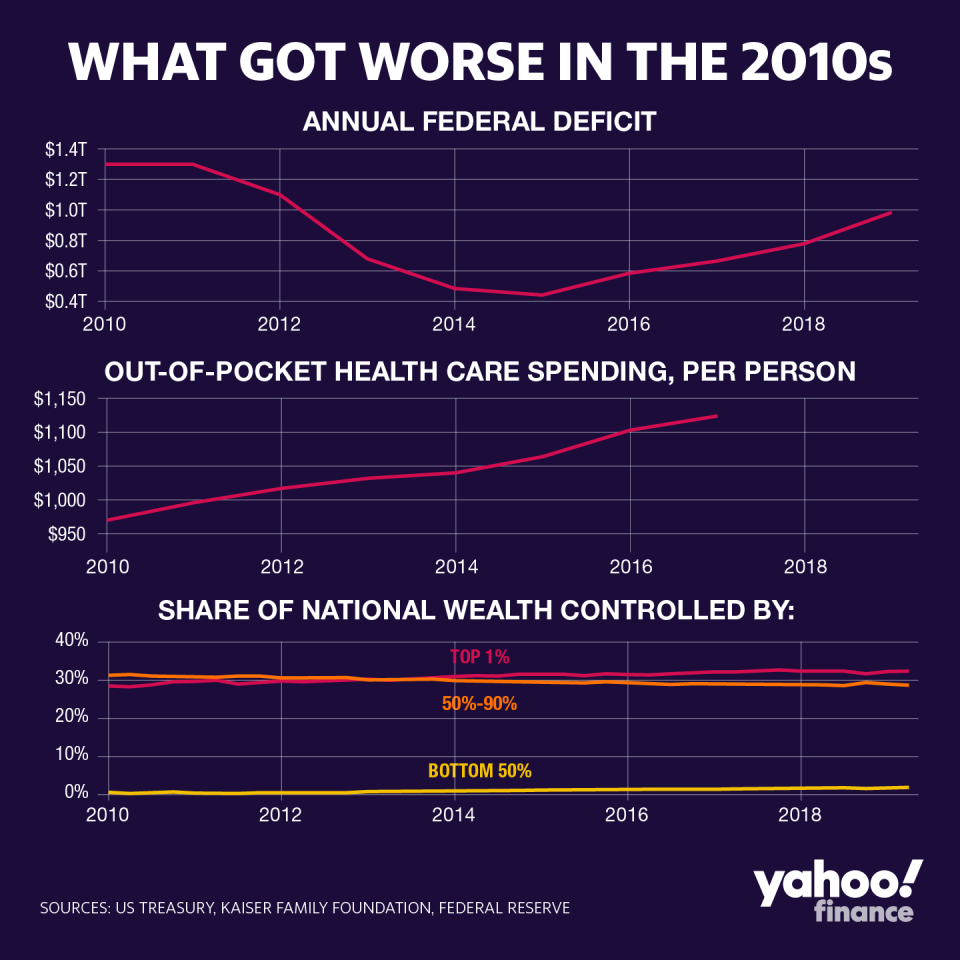

Worsening class divides. The rich have more, and the rest want some of it. The deep recession and stock market crash that lasted from 2007 to 2009 hit everybody. But the rich have more than recovered, while the middle class has muddled along. The share of national wealth controlled by the richest 1% of households rose from 28.5% in 2010 to 32.4% this year, according to Federal Reserve data. Wealth controlled by upper-middle income households fell from 39.6% to 37%. And the share held by the bottom half of households remains low, rising from 0.6% to 1.9%. On income, the gap between low and high earners is now the largest in 50 years, by one measure. Wealth and income inequality have been worsening for 40 years, with a reckoning probably due at some point. Calls for a wealth tax on “ultramillionaires” may just be the beginning.

Debt-fueled growth. The late 1990s were a period of prosperity similar to the last couple of years, with one crucial distinction. The economy back then was so strong that tax receipts soared and Washington actually ran a surplus for four years straight, from 1998 through 2001. The opposite is happening now. The economy is growing (slowly), but federal deficits are soaring, which suggests some of that growth comes from borrowed money rather than economic fundamentals. The annual federal deficit did drop from 2010 through 2015, as it should during a recovery. But then it ticked back up, before lurching toward $1 trillion after the Trump tax cuts went into effect in 2018. The $23 trillion national debt isn’t a problem now, but it will be someday, requiring an unappetizing mix of tax hikes and spending cuts.

Dependence on ultralow interest rates. To combat the Great Recession, the Federal Reserve cut short-term interest rates from 5.25% to 0 over a course of three years. It started raising rates again in 2015 but only got up to 2.25% before starting to cut again this year. Short-term rates are now around 1.5%. That’s okay, but the next time there’s a recession, the Fed will likely have less than two points of rate cuts to use as monetary stimulus, compared with more than 5 points the last time around. Think negative rates will solve the problem? Think again. If negative rates hit the United States, it would distort the fundamentals of global financial markets and possibly wreak havoc. In the next downturn, the Fed will probably have to rely on unconventional stimulus measures, or simply stimulate less.

Runaway health costs. The cost of health care has been rising faster than overall inflation since the 1980s, and a huge consequence of that will arrive in the next decade. The trust fund that helps finance Medicare, the retiree health program, is likely to be depleted by 2026, which means Medicare won’t have enough money to pay its costs in full. If nothing changes, the fund will be able to pay 89% of costs in 2026, with that portion declining to 77% by 2046 and then drifting gradually back up. Experts have been predicting a Medicare crisis for years, based on the rising cost of care, longer life expectancies and a growing population. Congress can fix the problem by raising taxes, cutting benefits or exploiting new efficiencies, but it won’t be easy. This mess looms as out-of-pocket health care costs for the typical family are rising as well. Many politicians claim to have solutions, but turning them into laws and regulations is notoriously difficult.

A steaming planet. The 2010s were the hottest decade on record, and each decade since the 1980s has been warmer than the last. A warming planet, caused largely by the burning of fossil fuels, portends profound challenges and possibly disasters, including melting glaciers, rising sea levels, widespread coastal flooding, more violent weather patterns and habitat disruption—including human habitat. Addressing the problem by developing new fuel sources and removing carbon from the atmosphere will take decades. Some nations are taking action, but President Trump refuses to acknowledge the problem and has pushed for more fossil-fuel development not less. So it’s somebody else’s problem, in the future. We may not be able to say that a decade from now.

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including “Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success.” Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman. Confidential tip line: rickjnewman@yahoo.com. Encrypted communication available. Click here to get Rick’s stories by email.

Read more:

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.